Review: Facing Infinityby Jeff Foust

|

| One researcher mentions that, while she is from Italy, she has worked in the US, UK, and France, moving from job to job. When asks if she is a nomad, she responds, “No, I’m an astrophysicist.” |

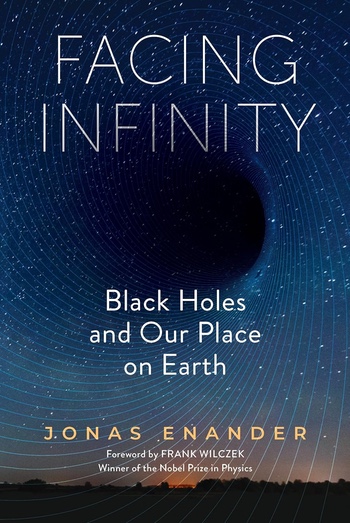

The book Facing Infinity starts down a familiar path. Jonas Enander, a Swedish physicist and science communicator, examines the history of studies of black holes, from initial concepts centuries ago of stars so massive light could not escape to modern efforts like the Event Horizon Telescope to take the first images of supermassive black holes at the heart of galaxies. The book at times has a travelogue feel, with the author touring observatories atop Maunakea in Hawaii and the LIGO gravitational wave observatory in Washington state and going to conferences in Paris and Spain.

The focus on the book is as much on the people who do the science as it is on the science itself, recounting the histories of earlier scientists and talking to present-day scientists. The latter provides perspectives regarding both what drew them to their field as well as the challenges they face. One researcher mentions that, while she is from Italy, she has worked in the US, UK, and France, moving from job to job. When the author asks if she is a nomad, she responds, “No, I’m an astrophysicist.”

The third and final part of the book, though, makes a sharp turn. Enander turns his attention to the influence black holes—or, rather, studies of black holes—have had on humanity. That includes the impact of astronomy and space research on indigenous peoples, such as the protests by native Hawaiians about observatories on Maunakea and those by locals about conditions in French Guiana, home to the spaceport that launched the James Webb Space Telescope. “Even the term ‘black hole’ has a bloody colonial history,” he writes, linking the term to the “Black Hole of Calcutta” during Britain’s colonial rule in India.

Black holes have other influences. The study of quasars, linked to black holes, provide fixed points of reference to help monitor even the smallest terrestrial changes, like the movement of landmasses. Such work showed, for example, that Europe and North America are moving apart due to plate tectonics, and how land is rising and sinking. (He describes a fascinating connection between astronomy and Earth science: Alfred Wegener, who first proposed plate tectonics, was trained as an astronomer. He was also a German army officer in World War I and crossed paths with another officer, Karl Schwarzschild, an astrophysicist who developed a formula for a black hole during free time while serving in the war.)

The result is a book that makes the case that black holes are more than just an intellectual curiosity. Studies of black holes have an impact on society in ways that go beyond simply better understanding the nature of the universe, while black holes themselves may play a role in life on Earth: some astrophysicists believe they help distribute the elemental building blocks of life throughout the universe. No wonder black holes are such an attractive subject.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.