The P-Camera Experimentby Dwayne A. Day

|

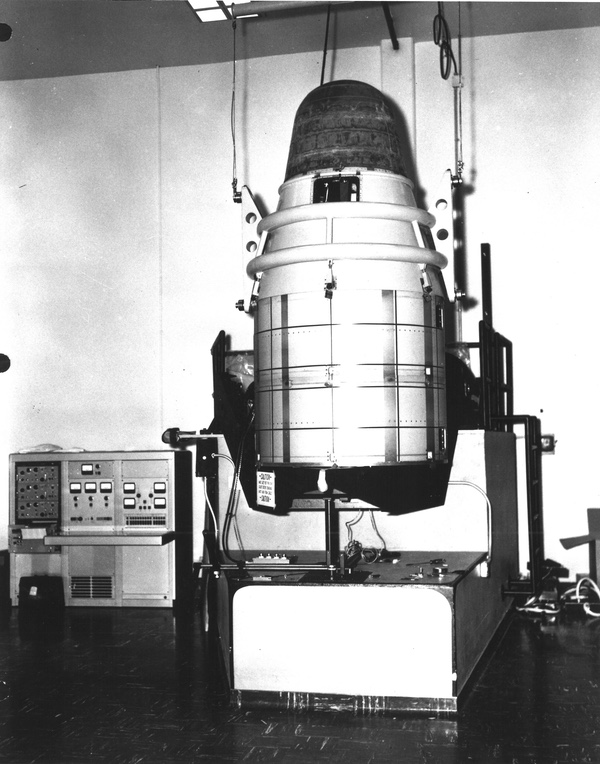

In March 1963 the Air Force launched the first LANYARD reconnaissance satellite. LANYARD carried a more powerful camera than the proven CORONA system. This launch failed, however. It prompted a rush effort to develop a reconnaissance camera for a special mission. (credit: Peter Hunter Collection) |

At the time, the National Reconnaissance Office, which was responsible for managing America’s intelligence satellite program, was developing a new, more powerful satellite named GAMBIT, then scheduled for launch in the summer. GAMBIT was designed to produce higher-resolution photographs using new and unproven technology, and some within the intelligence community had their doubts about it.

In April, Director of Central Intelligence John McCone wrote to National Reconnaissance Office Director Brockway McMillan that “since the success of the GAMBIT system is quite uncertain,” it was a good idea to purchase additional LANYARD reconnaissance satellites to cover the period August 1963 to August 1964. [1]

The KH-4 CORONA reconnaissance satellite had enough room in the conical section between the reentry vehicle (top) and the dual reconnaissance cameras (in the cylinder) to carry a small but powerful camera known as the "P-Camera" named after reconnaissance advisor Dr. Edward M. Purcell of Harvard. The camera port would have been on the side facing the wall. (credit: NRO) |

But McCone was also concerned about the future of satellite reconnaissance. In April, he flew to Boston to persuade Dr. Edward M. Purcell of Harvard to chair a panel to survey the future of reconnaissance satellites and ways to improve their imagery.

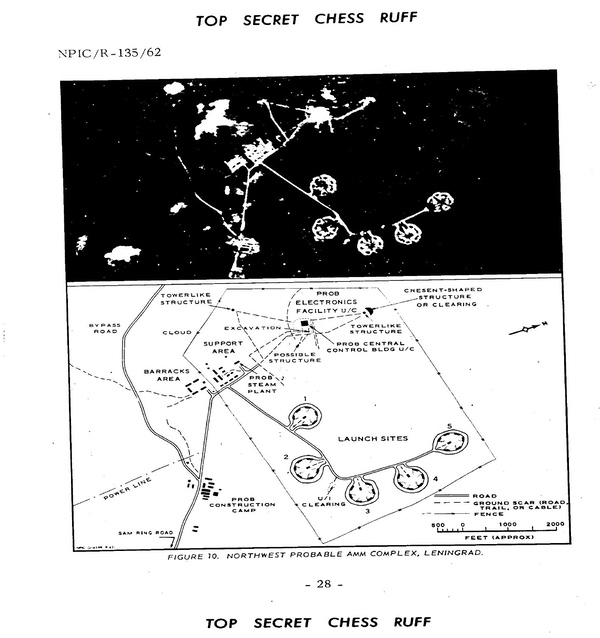

During the meeting, McCone also mentioned to Purcell the need to obtain imagery of the suspected anti-ballistic missile site at Leningrad. Purcell suggested a method of obtaining imagery quickly—even before the first GAMBIT launch scheduled for that summer: put a telescope and strip camera in an upcoming CORONA satellite specifically to photograph the Leningrad site. McCone passed Purcell’s suggestion to the CORONA program office, which took it to Itek, developer of both the CORONA and LANYARD cameras.

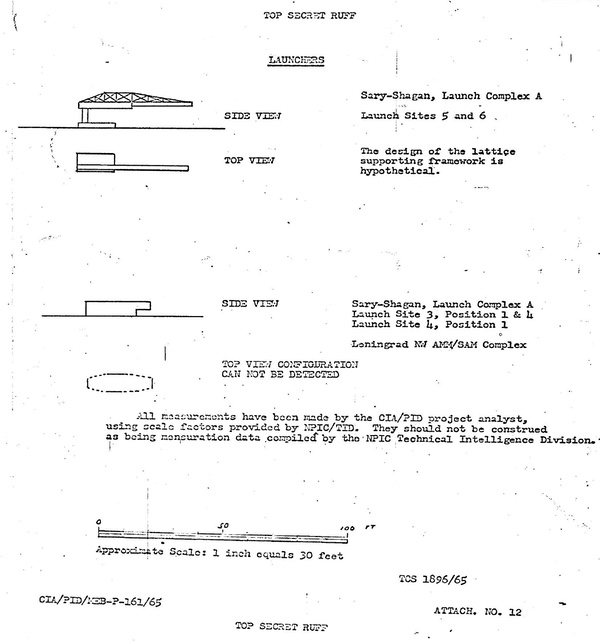

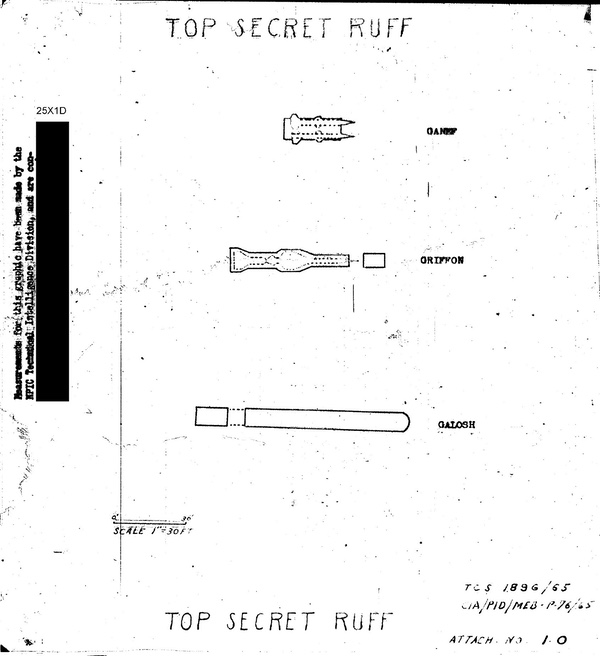

Illustrations from a 1962 intelligence report on a suspected anti-missile missile (or anti-ballistic missile) launch site near Leningrad. The intelligence community needed higher quality satellite photos to determine what this site was. (credit: CIA) |

Itek’s engineers developed a proposal for a 240-inch (610-centimeter) focal length Cassegrain telescope using “folded optics” and attached to a 127-millimeter strip camera. This was ten times the focal length of the CORONA camera that was then operational (for comparison, the KH-8 GAMBIT-3 had a focal length of 175.6 inches, or 446 centimeters). This was soon known as the P (for Purcell) camera experiment, or the P-Camera. Amazingly, they managed to build it in only two months, although it is likely that they were collaborating with Purcell before they started building.

In California, Lockheed engineers came up with a way to use the empty space in the conical film transport area of a KH-4 CORONA-MURAL satellite. This was where the film traveled to the single reentry vehicle. They built a dummy unit to fly in a CORONA spacecraft and cut an opening in the side of the spacecraft with a door that would be blown off by a pyrotechnic device after orbital insertion, like the doors for the two CORONA-MURAL cameras.

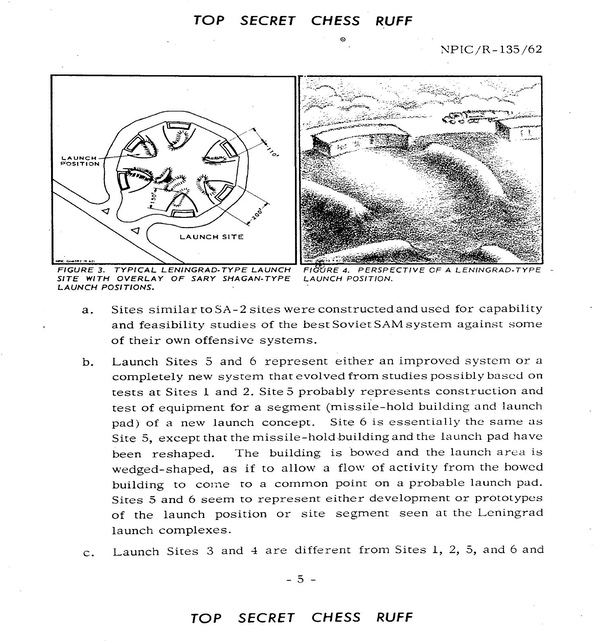

In later June 1963, the Air Force launched a CORONA reconnaissance satellite into orbit using this Thor rocket at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Also onboard this satellite was the "P-Camera" specifically designed to photograph the suspected anti-ballistic missile site near Leningrad. Although the CORONA operated properly, the cover door for the P-Camera did not eject and the film was blank. (credit: NRO) |

On June 12, 1963, a CORONA mission was launched from Vandenberg Air Force Base carrying the dummy P-Camera. The flight was intended to determine if the P-Camera would disrupt the main camera operations, if the rocket could carry the heavier load into orbit, and if the Agena spacecraft could still stabilize the spacecraft. The CORONA mission went normally.

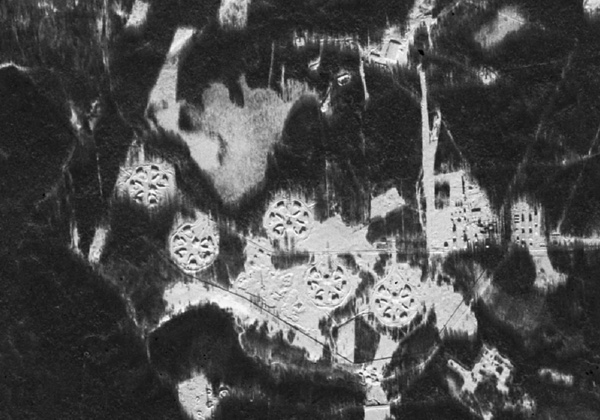

IA higher resolution GAMBIT reconnaissance satellite took this photo of a suspected anti-ballistic missile site near Leningrad. By the time the U.S. intelligence community obtained good resolution photos of the site, the Soviet Union had shifted its ABM focus to defending Moscow. No substantial ABM defenses were built at Leningrad. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

On June 26, a second CORONA mission, number 9056, was launched carrying the only P-Camera onboard along with a standard CORONA-MURAL camera. Unfortunately, telemetry indicated that the P-Camera’s door had not blown off as planned. In the hopes that this was faulty telemetry, Lt. Col. Vernard Webb, the CIA chief of satellite operations on the West Coast, ordered that the camera be turned on during the next pass over Leningrad. When the Satellite Recovery Vehicle was deorbited on June 30 and the film recovered and developed, it was blank, indicating that the optical-port door had not blown off.[2]

Probably because it was rushed and unsuccessful, there are no surviving illustrations or photographs of the camera. Its design remains mostly an enigma, but it would be interesting to know how such a large focal length camera was fit into a relatively small volume. The “P-Camera experiment,” as it became known, may have been inspired by the March launch failure of the first LANYARD mission, as well as McCone’s lack of faith in the GAMBIT. It was a backup to the backup program. Now that it had failed, they would have to wait for better imagery of that suspect site in Leningrad.

By 1965, the US intelligence community was gaining a better understanding of Soviet ABM developments. These excerpts from intelligence reports indicate some of what was known about Soviet ABM missiles and their launchers. Most Soviet ABM development was focused on defending Moscow, and soon that effort began to slow down as it became evident to the Soviets that ballistic missile defense was extremely difficult, and expensive. (credit: CIA) |

Endnotes

- Robert Perry, “A History of Satellite Reconnaissance, Volume IIB – SAMOS E-5 and E-6,” October 1973, pp. 378; 381-382.

- Frederick C.E. Oder, James C. Fitzpatrick, and Paul E. Worthman, “The GAMBIT Story,“ National Reconnaissance Office, 1988, p. 181; CORONA Mission 9056 Performance Report, July 8, 1963, pp. 6-7.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.