Above us, always: Chronicling humanity’s home in space, in real timeby Emily Carney

|

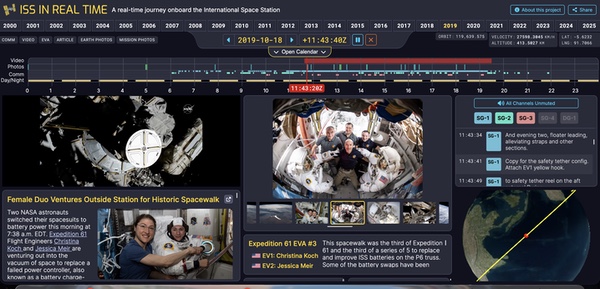

| Ben Feist and David Charney, two of the thinkers behind Apollo in Real Time, have expanded the concept behind that project to the new ISS in Real Time. |

But the more human moments aboard the world’s premier scientific platform in space have tended to capture the public’s eye, such as 2019’s first all-woman spacewalk carried out by astronauts Christina Koch and Jessica Meir, and the thrill to follow many astronauts’ journeys in near real-time as they chronicle their missions on social media, something that did not yet exist when the ISS was first “opened for business” in 2000.

But social media hasn’t quite been able to depict the station’s daily operations in “real time.” Enter Ben Feist and David Charney, two of the thinkers behind Apollo in Real Time, one of the most exciting resources made for space enthusiasts and historians alike in the last decade. The two have expanded the concept behind that project to the new ISS in Real Time, which aims to capture the station’s history as it happened. I took some time to discuss ISS in Real Time with Feist and Charney, asking them about the workload behind such a large endeavor and how the project will help shape the legacy of the ISS as it approaches nearly 30 years in space and with the end of the program now in sight.

NASA astronauts Jessica Meir (left) and Christina Koch are inside the Quest airlock preparing the U.S. spacesuits and tools they will use on their first spacewalk together. (credit: NASA) |

Real-time storytelling from low Earth orbit

Emily Carney: You’re well known for your Apollo in Real Time projects. However, the ISS in Real Time is a much larger endeavor. What were some of the biggest challenges, maybe even technical challenges, of assembling this project of such an enormous scale? How long did it take?

Ben Feist: Apollo in Real Time was a bit of a labor of love in that I was touching the data itself. All of that analog material needed to be extensively cleaned up so it could behave like healthy digital data that could be put into a digital medium like apolloinrealtime.org.

I knew that if I was going to try to make a real-time experience for ISS, I would have to have a rule: no manual intervention. If I were to start touching the ISS data manually, a photo caption here, a transcript correction there, I would be lost because there’s just so much of it. ISS data has the advantage of having started out as digital data, so making ISS in Real Time became an exercise in building transformative “pipelines” that take the historical data wherever I might find it across the internet, and transform it into a format I can use to serve an online multimedia presentation of it. This means that even if all of the data was deleted from ISS in Real Time, I could re-run these pipelines and reconstitute all of the mission data for it. This took about a year to work out and about five months of pipeline processing time (it’s computationally expensive, especially the transcript generation).

The other huge technical challenge was building the interactive experience itself. We had to solve problems like, how can you make a navigational visualization that shows 25 years of anything and actually works, also on mobile. This wasn’t easy to get right, but luckily my collaborator, David Charney is a world-class UX [user experience] designer, and I dare say we cracked it.

David Charney: To add a little more, I would say one of the design challenges that we had with ISS in Real Time is how to make the site feel consistent even though the available content on a given day varies so much. One day might have an article and the ISS location on the Earth, another day might have video, space to ground audio, a thousand photos, etc., and we didn’t want it to be jarring going from a day without a lot of content to a day with a lot. With a lot of the materials Ben included, I think even a day that doesn’t have a lot of material, can still be interesting.

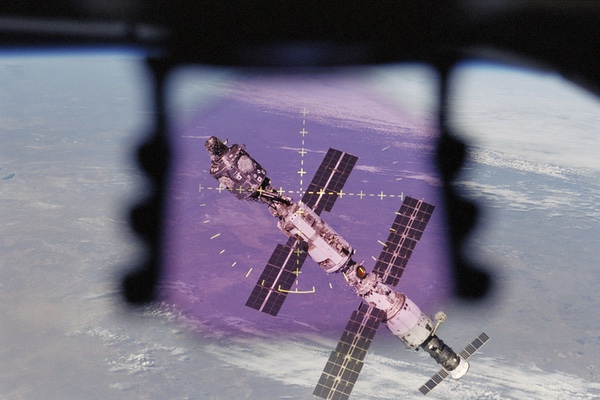

Carney: In 25 years, we’ve seen the ISS go from two smaller conjoined pieces to the sprawling complex we see now in many photos shared by US and international crews. How does ISS in Real Time address the changing nature of the space station over time?

| If we could determine that something was authentic mission material, and we could determine where it occurred in time, and it was public, it was included. |

Feist: The website itself doesn’t address the ISS’s changing nature itself, but the historical material being played back every day sure does. You can watch the ISS being constructed as it happened and watch as each iconic photo is taken throughout assembly. It would be great if we could have a 3D representation of the ISS to show how it changed over time, but we ran out of time before our “deadline” to flesh this out. We really wanted this to be available to everyone in time for the 25th anniversary of continuous human presence onboard (November 2, 2025).

Charney: Yes, perhaps in the future we will show the “current state” of the ISS. Currently, there are still many images from approaching spacecraft and EVA video and imagery that show a handful of the different configurations over the years.

Carney: The ISS years have also seen a wide variety of spacecraft visit the space station. How does the project explain all these developments throughout the decades?

Feist: Every flight to and from the ISS is logged as part of the website’s timeline of events. You can read about each flight of course, but there are some more interesting interactions available, like moving your cursor across our 25-year-long timeline and watching flights come and go, and the roster of crew onboard change with every small movement of your mouse. Or, watch as a spacecraft docks and notice the roster of people onboard change at that very moment. It’s in these kinds of moments that I hope the website can help people to feel the immense scale of what the ISS program has achieved.

This view of the International Space Station (ISS) was captured with a 35mm handheld camera through the Space Shuttle Atlantis' crew optical alignment system (COAS) during undocking operations. The undocking took place at 10:46 p.m. (CDT) on September 17, 2000. (credit: NASA) |

Carney: Given the sheer scale of the ISS program, how did you decide what content to include and what to leave out?

Feist: Basically, we didn’t leave anything out. If we could determine that something was authentic mission material, and we could determine where it occurred in time, and it was public, it was included.

I’m in the process of coming up with more elaborate ways to determine when things occurred, which will allow for the inclusion of even more material. For example, now that we have transcripts of communications for over 5,000 days onboard, if we find a video somewhere with no timing metadata, but we can clearly see that it took place onboard, we can match what people are saying in the video with the comm transcripts and reverse engineer when that video happened. It’s tricks like this that really show the value of disparate, contextual data being pulled together to make something that wasn’t there before. It’s also a lesson in the value of storing good metadata with mission material. You never know how someone might want to use that material later.

Carney: How does the project capture the human experience aboard the station, like the quieter, more everyday moments of life in orbit?

Feist: I think the most human moments are captured in some of the more casual communication chatter and fun crew photos that were taken onboard. The ISS program isn’t like Apollo in that recordings of every waking moment are available (either onboard or in mission control). On the ISS, people actually live there for long periods, so it’s understandable that every moment isn’t available. People need their privacy.

Carney: Many non-space enthusiasts aren’t aware that the ISS program is still evolving. How will ISS in Real Time continue to provide updates? The previous Apollo projects had already “happened,” but the ISS is still orbiting the Earth.

| This project rejects the “summary” approach. Instead, it gives you the real events that occurred firsthand and does its best to get out of the way. |

Feist: That’s a great question. NASA continues to release mission data in a regular cadence, and because of our pipeline data processing approach, we will be able to continue to update ISS in Real Time as new data becomes available. It’s like backfilling the mission with additional data. As data becomes available, the website just gets better. If you visit today’s date, it will show you where the ISS currently is over the Earth, but it probably won’t have today’s data yet. It might have yesterday’s, though if you time your visit just after a data update.

Carney: What do you think historians, perhaps decades from now, long after the ISS has deorbited, can learn from your project? What do you think the ISS’ legacy will be?

Feist: Wow, you know how to ask the tough questions. I hope that this project can contribute to the human experience aspect of the mission. This project rejects the “summary” approach. Instead, it gives you the real events that occurred firsthand and does its best to get out of the way. No narrative.

Apollo in Real Time lets you get to know the crew in a personal way and share in their excitement. ISS in Real Time endeavors to do the same. To assist with public discussion of events onboard, we have created an old-school message forum where people can share the things they discover. Anything. The website allows you to link to any second over the past 25 years. For example, the first all-female spacewalk or just some amazing pictures of the moonrise above the Earth. I hope historians can assemble there and we all learn new things about the past 25 years in orbit.

Charney: Yeah, that is a great question. The more data we can add, the more day-to-day activity and moments will appear throughout the 25-plus years. I think people will learn a lot more about the science that occurred, learn about the crew and how they worked together, and with so many Earth photos and observations, a lot more about our home planet, too.

ISS in Real Time can be experienced by visiting https://issinrealtime.org/. If you’d like to see an overview of ISS in Real Time, check out this YouTube video courtesy of Ben Feist.

Many thanks to Feist and David Charney for discussing the project with me.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.