Stilsat-1: A Russian-owned and Chinese-built satellite watching Ukraine (part 2)by Bart Hendrickx

|

| Stilsat-1 is considered a technology demonstrator for later Stilsat satellites, all of which will be manufactured in Russia under the supervision of Stilsoft. |

The satellite is being operated by the Russian private company Stilspace, a subsidiary of Stilsoft, which is in overall charge of the project. There are strong indications that it is mainly being used to support Russia’s war effort in Ukraine. Russia may also be receiving high-resolution imagery from Taijing-3-01 and Taijing-3-04, two other MinoSpace satellites with similar capabilities that are likely being controlled by China itself and which Stilsoft also seems to refer to as Stilsat-1. So far, that is the only way to explain some of the conflicting information that has emerged on the project.

Russian-built Stilsat satellites

Stilsat-1 is considered a technology demonstrator for later Stilsat satellites, all of which will be manufactured in Russia under the supervision of Stilsoft. The idea essentially is to mate the Chinese optical system to a Russian-built bus. As of late 2023, the plan was for China to build and deliver the optical systems for Stilsat-2 and Stilsat-3. After that, Stilsoft would produce them in-house based on Chinese blueprints. Stilsoft’s ultimate goal is to produce satellites that will be more than 90% Russian-made. [1]

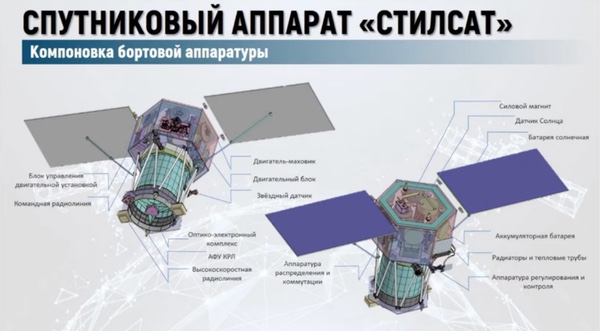

The currently planned version of Stilsat (the one seen in the title image) is slightly different from the one initially presented in late 2023. The most obvious change is the addition of a third solar panel to the hexagonal bus.

Original version of the Russian-built Stilsat. Source |

Work on the Russian-built versions of Stilsat has been underway for at least two years. By late 2023, Stilsoft had placed about ten orders with Russian organizations for the follow-on Stilsat satellites. Among the Russian-built systems will be an ion propulsion system using xenon. This will be used to move the satellites to their final orbits following separation from the upper stage, to carry out orbit corrections during the operational phase of the mission and to remove them from their operational orbits at the end of the mission. Test firings of the propulsion system for Stilsat-2 had reportedly been completed by early July 2024. [2]

Some parts for Stilsat will be delivered by academic institutions. The ELFOKS laboratory of the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology (MIFT) will provide optical sensors for the orientation and stabilization system and the North Caucasus Federal University (SKFU) in Stavropol will build lightweight solar panels using raw materials easily accessible in Russia, including sapphire. This is seen as part of Russia’s so-called “import substitution” policy introduced in the wake of Western-imposed sanctions. [3]

One other element of the Russian-built bus is a high-speed X-band radio system to downlink images to the ground. Stilsoft announced in January 2024 that it was developing such a system for Stilsat-2. It will use electrically steerable phased-array antennas that do not require the satellites to change their orientation for data downlink sessions. The data rate will be between 1,200 and 1,800 megabits per second (Mbps), with the ultimate goal being to reach a capacity of 2,400 Mbps. Uplink of commands to the satellites will also take place in the X-band. [4]

In August 2024, Stilsoft was given permission by Russia’s State Commission for Radio Frequencies to use two frequency ranges in the X-band, namely 7,190–7,250 megahertz for uplink and 8,025–84,00 megahertz for downlink. [5] A request to use these frequencies was recently filed with the International Telecommunication Union. [6] At the request of the Russians, China provided a simpler S-band command uplink system for Stilsat-1, probably to make it compatible with the ground control systems currently available to Stilsoft. [7]

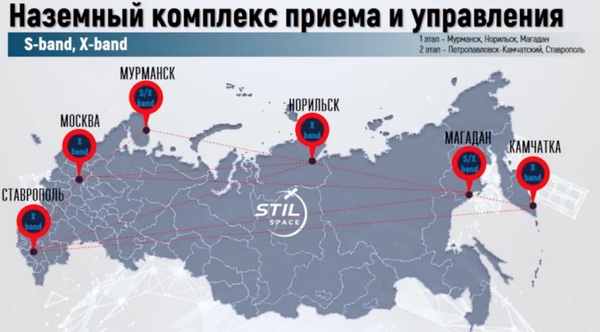

Stilsoft is planning a network of six ground stations to receive data from the satellites. Stations in Murmansk, Norilsk, and Magadan were expected to come online first, followed by three more in Moscow, Stavropol, and on the Kamchatka peninsula. During a presentation in June 2024, Stilspace’s Anton Burmak said that only two stations were available at the time for Stilsat-1 and that this was significantly hampering the receipt of data. One was in Murmansk and the other, apparently a temporary one, was in Moscow.

Ground stations for Stilsat. Source |

Stilsoft has given some details on the facilities where it intends to produce the Stilsat satellites. What it calls “pilot production” was supposed to take place on the premises of a former metallurgic plant (“Stankolit”) in the Butyrski district several kilometers north of Moscow’s city center. This already houses the mission control center for Stilsat-1 as well as offices for Stilsoft’s space design bureau. By the time of the June 2024 presentation, work was well underway on turning an old warehouse into a clean room for satellite production with a reported capacity of two satellites per year. The assembly of Stilsat-2 was expected to begin here in late 2024. [8]

Stilsoft site in northern Moscow. Source: Google Street View. |

Satellite clean room under construction at the Moscow facility in mid-2024. Source |

Apparently, the facilities in Moscow are just temporary. The idea was for mission control and the space design bureau to be moved in 2026 to a new site near Stilsoft’s home office in Stavropol. Serial production of the satellites and their optical systems was to begin that same year in Nevinnomysk, a town about 60 kilometers south of Stavropol. Stilspace’s website gives a production capacity of 30 satellites and optical systems per year.

It is unclear why such high production numbers are required. Stilsoft’s official objective is to operate a constellation of just nine satellites spread over three orbital planes (three per plane). The launch dates for the Russian-built Stilsat satellites have slipped considerably in recent months. In late 2023, the plan was to launch Stilsat-2 in the fourth quarter of 2024, followed by Stilsat-3, 4, and 5 in the third quarter of 2026, Stilsat-6 in the first quarter of 2027, and Stilsat-7, 8, and 9 in the fourth quarter of 2027. By June 2024, the launch of Stilsat-2 had moved to the second quarter of 2025, with the launch dates for the following satellites remaining unchanged. The dates now given on Stilspace’s website are:

- Stilsat-2: second quarter of 2027

- Stilsat-3: third quarter of 2028

- Stilsat-4, 5, 6: fourth quarter of 2031

- Stilsat-7, 8, 9: fourth quarter of 2033

Stilsoft also intends to orbit a constellation of radar satellites, benefiting from the experience it has gained with developing ground-based radar systems. No timelines for these launches have so far been given.

Stilsoft has been remarkably quiet about its satellite plans in recent months, with no reason given for the launch delays. In April this year, there were reports about massive layoffs in the company as a result of dwindling government orders. Company officials said they would focus on “cost-effective projects” such as its satellite program and export products, indicating that its satellite business was not being affected by the decline in orders. [9] Space-related vacancies published by Stilsoft in recent months show that it is still actively working on its satellite projects.

| Stilsoft has been remarkably quiet about its satellite plans in recent months, with no reason given for the launch delays. |

Confusingly, a satellite looking exactly like Stilsat has surfaced recently under the name KOEN, a Russian acronym for “Electro-Optical Observation Complex”. KOEN is one of three types of high-resolution optical Earth observation satellites which have been given grants under the National Technological Initiative (NTI), an effort to stimulate the development of Russian high-tech industry sectors. According to NTI documentation, Stilsoft and Stilspace are developing the satellites for a startup called MT-LAB, which will apparently act as the operator of the satellites. [10]

KOEN weighs 500 kilograms, which is 80 kilograms heavier than the maximum mass given for Stilsat. The goals are the same as those announced for Stilsat, including three of the four that were earlier linked to Russia’s “security agencies”, more particularly “optical reconnaissance,” “detection and uncovering of objects,” and “planning work in the new territories” (a likely reference to the occupied territories of Ukraine.) Whether future Stilsat satellites will still focus on Ukraine depends, of course, on how much longer the conflict drags on.

Goals and characteristics of KOEN. Source |

All this appears to be a departure from earlier plans in which Stilspace was to be the satellite operator, the role it is now performing for Stilsat-1. Unlike Stilsoft, MT-LAB signed up in early 2023 to participate in the implementation of a Roscosmos roadmap calling for closer cooperation between the private space industry and the government. As confirmed by a Roscosmos official, the Stilsat-1 mission is taking place outside the framework of that roadmap, probably because the satellite was urgently needed to provide coverage of the war in Ukraine (see part 1). That may not apply though to future Stilsat missions, which would explain why MT-LAB has taken over the role of satellite operator.

Last September, the TASS news agency reported that what it called a “dynamic model” of KOEN had undergone a full cycle of vibration and other tests at the Progress Rocket and Space Center (RKTs Progress) in Samara. [11] This is a leading Russian manufacturer of optical imaging satellites for both civilian and military purposes that operates under the wings of the Roscosmos State Corporation. Its involvement may suggest that Stilsoft has also relinquished the role of assembling the satellites. Strangely enough, the TASS report said the first KOEN launch was expected in 2026, much earlier than the launch period for Stilsat-2 seen on Stilspace’s website (the second quarter of 2027.)

The two other privately developed submeter resolution optical imaging satellites that have received NTI funding are EOS-O (0.5 meters) and Kinosputnik (0.8 meters), which are being developed by NPK Barl (with MT-LAB serving as the operator) and Sputnix, two other signatories to the Roscosmos roadmap. The first launches are expected in the coming two years. They should be joined by submeter-resolution satellites that are being built by some of Russia’s traditional satellite manufacturers. These are Resurs-PM (RKTs Progress), Piksel-VR (NPO Lavochkin), and a joint Russian-Belarusian satellite called RBKA (VNIIEM Corporation). Officially, these are civilian satellites, but it is perfectly possible that their images will be used for military purposes as well. There is, in fact, convincing evidence that Resurs-PM has been at least partially militarized. [12]

Other Chinese-Russian cooperation in remote sensing of Ukraine

Stilsat-1 is unique in that Russia itself is operating a Chinese-built satellite to acquire high-resolution imagery of the battlefield in Ukraine. However, Russia has also sought other ways of obtaining imagery from Chinese remote sensing satellites to compensate for deficiencies in its own satellite coverage. A company called AO Rakurs, which distributes imagery from remote sensing satellites to Russian users, signed agreements with two Chinese companies not long after having been denied access to data from Western remote sensing satellites in February 2022. In March 2022, it concluded a deal with HEAD Aerospace, which supplies data from more than 90 Chinese optical and radar imaging satellites of the Superview, Jilin, Gaofen, and ZY series with a resolution of up to 0.3 meters. Three months later it inked a deal with Spacety, another Chinese company, to supply data from two Chinese radar imaging satellites (HiSea-1 and Chaohu-1) with a resolution of up to 0.5 meters. [13]

Both HEAD Aerospace and Spacety were later put on the Western sanctions list on suspicion of having furnished remote sensing data to help Russia in its war effort in Ukraine. HEAD Aerospace came under sanctions from the US in April 2023 for having supplied imagery of locations in Ukraine affiliated with the Wagner Group, the state-funded private military company that was headed by Yevgeni Prigozhin. [14] Wagner was active on the battlefield in Ukraine until infighting between Prigozhin and the Russian military establishment led to a short-lived rebellion by Wagner mercenaries against the Russian government in June 2023. Prigozhin subsequently died in a plane crash in August 2023.

In June 2024, HEAD Aerospace was also targeted by sanctions from the European Union, which accused it of having provided topographic data sets to the General Staff of Russia’s Armed Forces via AO Rakurs. A photogrammetric software program developed by AO Rakurs under the name PHOTOMOD is said to be “the main topographic sensing system” employed by the General Staff’s Military Topographic Directorate. [15] Based on documentation placed online by AO Rakurs, PHOTOMOD is also being used to process data from Stilsat-1. [16]

Spacety China was hit by US sanctions in January 2023 for its ties with Terra Tech, another Russian distributor of remote sensing data, including those received from Stilsat-1. It was believed to have provided Terra Tech with radar satellite imagery to enable combat operations in Ukraine by the Wagner Group. [17]

| Russia has also sought other ways of obtaining imagery from Chinese remote sensing satellites to compensate for deficiencies in its own satellite coverage. |

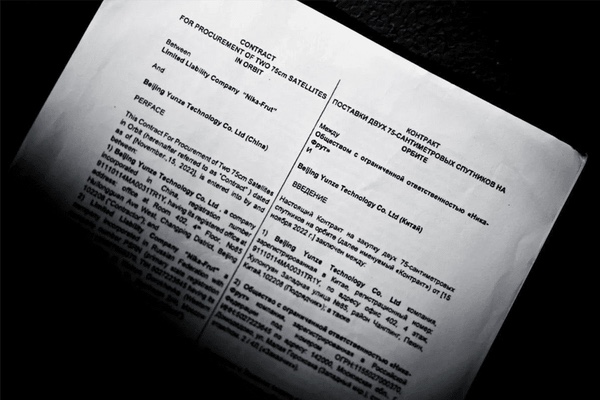

Several months into the war, the Wagner Group almost certainly acquired two Chinese optical remote sensing satellites already in orbit at the time to support its combat operations in Ukraine as well as its activities in parts of Africa. According to a contract seen by the French news agency AFP and signed in November 2022, Beijing Yunze Technology Co Ltd sold the two satellites to Nika-Frut, a company which was then part of Prigozhin’s commercial empire. The satellites were Jilin-1 Gaofen-03D 12 and 13, which were launched together with numerous other satellites (including MinoSpace’s Taijing-3-01) on February 27, 2022, and have a resolution of up to 0.7 meters. [18] Despite having been purchased by Wagner, the satellites were most likely operated by their Chinese owner (Chang Guang Satellite Technology or CGST). Under the contract, Wagner also acquired the right to order images from other satellites operated by CGST. Both Beijing Yunze Technology and Chang Guang Satellite Technology ended up on the US sanctions list in December 2023 for having supplied imagery to Wagner in support of its operations in Ukraine. [19]

Part of the contract between Beijing Yunze Technology and Nika-Frut. Source |

New allegations of China supplying satellite data to Russia emerged this October, when an official of Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service claimed there is evidence of high-level cooperation between Russia and China in conducting satellite reconnaissance of Ukraine’s territory to identify strategic targets for destruction, including targets belonging to foreign investors. [20] Kremlin spokesman Dmitri Peskov reacted by saying that Russia covers all its needs on the battlefield with its own capabilities, including satellites. [21] China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs responded it was not aware of any such cooperation, emphasizing the country’s neutral stance in the Ukrainian conflict. [22]

As outlined in this article, there is overwhelming evidence contradicting these statements. Although all the deals discussed here were between Russian and Chinese private companies, it is highly unlikely that they were made without government approval on both sides. In the case of Stilsat, Stilsoft itself has acknowledged that the project emerged from discussions between it and the country’s “security agencies” to come up with a quick way of obtaining high-resolution imagery of Ukraine. On the Chinese side, the sale of submeter satellite imagery to foreign customers is only allowed after formal approval by government agencies. [23]

So far, none of the criticism has specifically focused on the Stilsat project, even though its Chinese connection and its direct link to the war in Ukraine can be gleaned from open sources of information. Without a doubt, it represents the highest level of cooperation between Russia and China in the field of satellite remote sensing to date.

Status of Russia’s reconnaissance satellites

The need to purchase Chinese satellite technology and imagery to satisfy Russia’s reconnaissance needs exposes shortcomings in the country’s own military reconnaissance satellite programs. For much of the last decade, Russia had to rely on two optical spy satellites (Kosmos-2486 and 2506) launched in 2013 and 2015 under a project called Persona. Developed by RKTs Progress, these have an optical payload with a mirror 1.5 meters in diameter. The absence of maneuvers by these satellites in recent years may indicate they are no longer operational, although this is by no means certain. A smaller experimental reconnaissance satellite (EMKA) built by the VNIIEM Corporation was launched as Kosmos-2525 in 2018 and reentered three years later.

Two new reconnaissance satellite projects were initiated in 2014 and 2016 under the names Razdan and Razbeg. Razdan (with the military index 14F156) is a heavy (six to seven tons) class satellite developed by RKTs Progress, only two of which are known to be planned for launch. Razdan was originally believed to be a satellite with an optical system called Sevan using a 2.4-meter mirror. Although such a mirror is known to be under development, new information that has emerged in recent years suggests that Razdan will carry a more modest optical system. Named Lazurit-R, it probably is a modified version of the 1.5-meter mirror flown on Persona.

Razbeg (military index 14F169) is a new generation of much smaller reconnaissance satellites produced by the VNIIEM Corporation that will be launched in large numbers by both Soyuz and Angara-1.2 rockets. VNIIEM is also working on a military project called Geovysota that will probably see small observation satellites maintaining very low orbits (around 250 kilometers) with the help of an air-breathing propulsion system. Despite some earlier indications that the first Razdan and Razbeg satellites had already been placed into orbit, it now appears that both types of satellites are still awaiting their first launches. [24]

| Only five years ago, the director of the company that manufactures the Glonass satellites had expressed skepticism about buying Chinese-made electronic components for the satellites. Now it looks as if reality has caught up with Russia’s space industry. |

Russia does seem to be operating another series of small optical reconnaissance satellites that cannot yet be linked to any known project. Twelve of these have been launched since September 2021 by four Soyuz-2.1v and four Angara-1.2 rockets. [25] Four reentered not long after launch without having made any maneuvers, possibly as a result of onboard failures, but the others have spent months maintaining low orbits at altitudes around 300 kilometers, most likely with the help of an electric propulsion system. Orbit analysis clearly shows that some have worked in conjunction to maximize coverage of ground targets. The first satellites in the series were reportedly designated EO MKA and later ones OO MKA (their military index is rumored to be 14F178). Both abbreviations stand for “prototype of a small satellite”, indicating that the operational versions are yet to appear. It looks like these will be serially produced satellites that can be launched at relatively short notice.

Another unidentified low-orbiting satellite was orbited in November 2023 under the name Kosmos-2572. Since it was launched by the most powerful rocket in the Soyuz family (the Soyuz-2.1b), it most likely belongs to yet another project.

Russia currently has no operational military radar observation satellites in orbit. The only one believed to have been launched in recent years was Kosmos-2553 (internally named Neitron), which went into orbit in early 2022. Visual observations indicate that it began tumbling late last year and is no longer under control. Another type (Araks-R), which has been under development for more than a decade, is still grounded. However, it is not impossible that two civilian radar satellites currently in orbit (Kondor-FKA nr.1 and 2) are being partially used for military purposes.

Many of the delays suffered by these projects can probably be attributed to sanctions that the West has been imposing since 2014 on the export of space-rated electronic components to Russia. This has forced Russia’s space industry to seek alternative suppliers both at home and in other countries, including China. Plans to purchase Chinese-built electronic parts for Russia’s space program have been circulating ever since the introduction of the sanctions, but recently published court documentation has provided the first concrete evidence that such purchases are indeed taking place, more specifically for Russia’s Glonass navigation satellites, which also play a key part in the current war.

Only five years ago, the director of the company that manufactures the Glonass satellites had expressed skepticism about buying Chinese-made electronic components for the satellites. He described this option as a “temporary alternative” to which Russia would resort only if no homemade or Western electronic parts would be available, adding that any Chinese-built components would undergo “the strictest quality and reliability checks.” [26]. Now it looks as if reality has caught up with Russia’s space industry and that it is at least to some extent relying on China for such deliveries. This is just one more example of how Russia is turning to its neighbor to help it overcome some of the problems that its space industry is currently experiencing.

References

- Video of a presentation by Stilspace’s Anton Burmak, October 2023.

- Press release by Stilspace, July 3, 2024.

- Report by MFTI University, 2023, p. 68 ; Report by the TASS news agency, February 12, 2025.

- Press release by Stilspace, January 15, 2024.

- Article on the website of Comnews, August 26, 2024.

- Networks explorer page on the website of the International Telecommunication Union. The Stilsat frequency request was received by the ITU on June 18, 2025.

- See reference 1.

- Video of a presentation by Anton Burmak (1:49:15-2:05:15), June 27, 2024.

- Press report, April 30, 2025.

- Report by NTI, August 2025 ; Report by NTI, 2025.

- Report by the TASS news agency, September 30, 2025.

- Russian government procurement documentation published in late 2018 referred to a decision made on September 27, 2017 under which several Roscosmos projects, including Resurs-PM, would be carried out on the basis of “technical documentation provided by the Ministry of Defense”. At the same time, the launch of the Resurs-PM satellites was moved from Vostochny to the military Plesetsk cosmodrome.

- Press release by AO Rakurs, January 23, 2023.

- Press release by the US Department of State, April 12, 2023.

- OpenSanctions website.

- PHOTOMOD documentation published by AO Rakurs ; PHOTOMOD user guide published by AO Rakurs, p. 14.

- Press release by the US Department of the Treasury, January 26, 2023.

- Report by AFP, October 5, 2023.

- Press release by the US Department of the Treasury, December 12, 2023.

- Report by Ukrinform, October 4, 2025.

- Report by Reuters, October 6, 2025.

- Report by United24 Media, October 6, 2025.

- Article on the website of the Moscow-based Space Economy and Policy Research Center, August 8, 2025.

- B. Hendrickx, Upgrading Russia’s fleet of optical reconnaissance satellites, The Space Review, August 10, 2020. Also see project updates on the NASA Spaceflight Forum for Razdan, Razbeg, and Geovysota.

- These satellites were given the official names Kosmos-2551, 2555, 2560, 2568, 2574, 2575, 2577, 2578, 2591, 2592, 2593 and 2594.

- Court document published in July 2024 ; Article published in Vedomosti, September 27, 2020 ; More background in the Glonass thread on the NASA Spaceflight Forum (Reply 90).

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.