NASA Goddard and the dawn of international cooperation in spaceby Trevor Williams

|

| GSFC was initially intended to carry out all aspects of spacecraft design, even human spaceflight: the six-story Building 8 was designed to accommodate the Project Mercury staff. |

An international grouping of scientific organizations, the Committee on Space Research (COSPAR), was then set up to build on the collaborative work of the IGY. In March 1959, or just over a year after the launch of Sputnik, the United States made an offer to COSPAR to launch, at no cost, scientific experiments or entire spacecraft proposed by other nations [1, p. 462]. The United Kingdom and Canada both took the United States up on this offer, in the case of the UK for the launch of individual experiments integrated into a satellite built by NASA (Ariel 1), and for Canada the launch of an entire spacecraft built by that country (Alouette 1). Both of these missions heavily involved the newly established NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, and both led to extensive subsequent international space science collaboration which continues even to the present day.

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, 2010. (credit: NASA) |

Origins of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

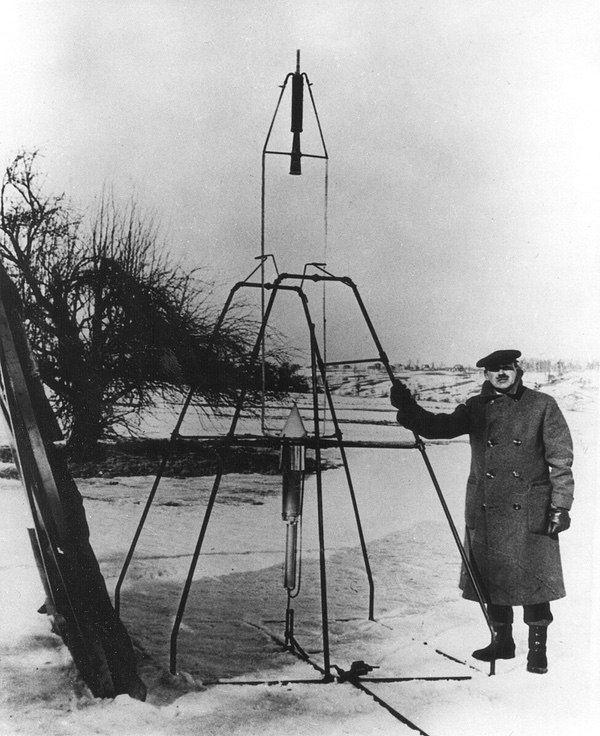

When NASA was created on October 1, 1958 it absorbed the facilities of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). It also incorporated two Army establishments, the Army Ballistic Missile Agency at Redstone Arsenal and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, plus the Vanguard rocket program from the Naval Research Laboratory. These covered the areas of aeronautics and launch vehicle design, but did not address spacecraft design and operations. A new center was therefore established to cover this area: carved out of land from the Dept. of Agriculture’s Agricultural Research Center in Beltsville, Maryland, it was initially named the Beltsville Space Center [2, p. 28]. On May 1, 1959, it was renamed the Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) in honor of the American rocketry pioneer Robert H. Goddard, who launched the first liquid fueled rocket from his Aunt Effie’s farm on March 16, 1926.

Robert H. Goddard and first liquid fueled rocket. (credit: NASA) |

GSFC was initially intended to carry out all aspects of spacecraft design, even human spaceflight: the six-story Building 8 was designed to accommodate the Project Mercury staff. Later, when the wide scope of space work became apparent, Goddard became focused on robotic missions, particularly those involving science: this has remained the key thrust of the center ever since. To accomplish these missions, until recently more than 10,000 space scientists and engineers worked at Goddard, making it the largest such center in the world. Many of these efforts have involved international collaboration, such as the Orbiting Solar Observatory (OSO), Orbiting Geophysical Observatory (OGO), Orbiting Astronomical Observatory (OAO), International Ultraviolet Explorer (IUE), Infrared Astronomical Satellite (IRAS), Hubble Space Telescope (HST), Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), Solar Terrestrial Relations Observatory (STEREO), and James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) programs. Leading the way for all of these were the first two collaborative space missions.

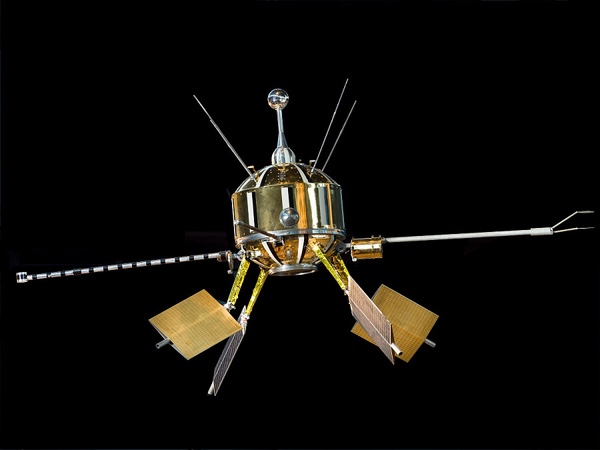

Ariel 1, the first international satellite

Ariel 1 was a collaborative effort between the United States and the United Kingdom to design, build, launch and operate the first international satellite. Initial discussions in late 1959 and early 1960 centered on proposals submitted to NASA by the British National Committee for Space Research [1, pp. 74-78] in response to the United States’ launch offer to COSPAR. This was only about two years after the flight of the first artificial satellite: at this point, the US had successfully launched a total of around 16 spacecraft. NASA Goddard was assigned responsibility for the construction and launch of Ariel 1, even though it had been in existence for less than a year. NASA was responsible for the design, management, launch, and operation of the spacecraft, as well as downlinking data and tracking. Design and operation of the on-board experiments, as well as their data reduction, was the responsibility of Great Britain.

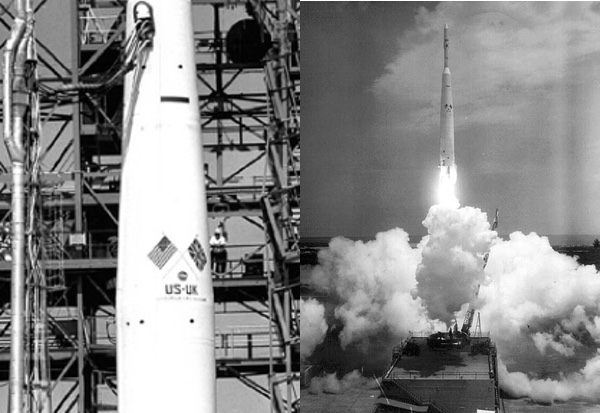

Ariel 1 had a mass of 62 kilograms and a design lifetime of one year. Its name comes from the spirit in Shakespeare’s The Tempest; in the play, Ariel serves the magician Prospero. Nine years later, the first British satellite to be put into orbit by a launch vehicle of British design, the Black Arrow [5], was in turn named Prospero. Ariel 1 was launched on April 26, 1962 into a 390-by-1,214-kilometer orbit by a Thor-Delta from Cape Canaveral. Upon release, it was spinning with the third stage at 160 revolutions per minute (rpm). A “stretch yo-yo despin” system, where the tip masses are attached to springs which extend while deploying, slowed the spin rate to 76.5 rpm. This was then further reduced by deployment of the spacecraft’s various appendages: four solar panels, two experiment booms, and two inertia booms (serving to balance the spacecraft). The resulting final spin rate at separation was 36.6 rpm [3, p. 14].

Ariel 1 Thor-Delta launch vehicle; note Union Jack on side. (credit: NASA) |

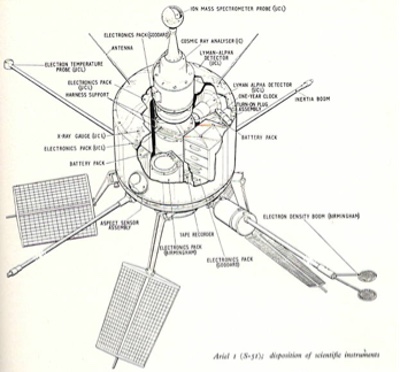

The seven instruments, produced by the British universities University College London (in association with the University of Leicester), Imperial College London, and the University of Birmingham, focused on the interaction between the Sun and the Earth’s ionosphere. Specifically, the experiments studied the ionization that occurs in the upper atmosphere, as well as the external energy sources (solar X-rays, ultraviolet light, and cosmic rays) that drive this ionization. All instruments apart from the University College London measurement of solar Lyman-alpha emission in the ultraviolet band, which failed during launch, operated well and yielded good results.

A similar division of responsibilities between the US and UK was taken for the follow-on Ariel 2, with one modification: since this spacecraft was a near copy of Ariel 1 rather than an original design, GSFC practice was followed and a portion of the fabrication was contracted out, in this case to Westinghouse Electric [4, p 6]. Ariel 2 was launched in 1964 and focused on radio astronomy. The subsequent Ariel 3–6 series, launched between 1967 and 1979 and studying various fields including ionospheric science, cosmic rays and X-ray astronomy, remained a US-UK collaboration but differed in that the spacecraft were entirely designed and constructed in Britain. All were launched on Scout launch vehicles; Ariel 1 had also been designed to launch on a Scout, but launch vehicle delays necessitated shifting it to a Thor-Delta.

| Ironically, one of the Ariel components that apparently suffered damage from Starfish Prime radiation was the kill switch that was designed to deactivate the spacecraft transmitter aftre about a year. |

Ariel 1 was one of several satellites that were seriously affected by radiation from the Starfish Prime nuclear weapon test that was carried out in space on July 9, 1962, less than three months after Ariel 1 was launched. Starfish initially caused all of the Ariel experiment sensors to become saturated; a few days later, on July 13, 1962, telemetry became erratic, and the spacecraft tape recorder failed at the end of July. In addition, radiation damage to the solar arrays and other electronics became evident. Because Starfish Prime had such a significant impact on the Ariel mission, it is worth discussing it in some detail.

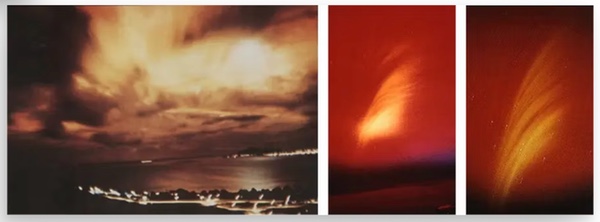

Starfish Prime

The American Starfish Prime [6] was the largest nuclear detonation ever conducted in space. It was one of five tests that made up Operation Fishbowl, which in turn was part of the 31-test Operation Dominic: this was set up in reaction to a Soviet announcement in August 1961 that they were ending a three-year moratorium on nuclear testing. Most of the Operation Dominic tests were of air-launched atmospheric weapons, but those of Operation Fishbowl were detonated in space.

Starship Prime over Hawaii. (credit: American Physical Society) |

Starfish Prime was launched on a Thor missile from Johnston Atoll and triggered at an altitude of about 400 kilometers. Its yield of 1.4 megatons gave rise to a stronger than predicted electromagnetic pulse (EMP) and the creation of an artificial radiation belt, raising the natural electron intensity of the inner Van Allen belt by several orders of magnitude. The strong EMP led, among other things, to the “Hawaiian streetlight incident” [7], where more than 300 street lights simultaneously failed at the time of the test, despite Hawaii being around 1,450 kilometers away from the explosion.

A subset of the electrons generated by Starfish Prime remained in space for up to five years, greatly exceeding some of the pre-test predictions of duration. This led to damage to several spacecraft in low Earth orbit, including Ariel 1. The spacecraft began exhibiting erratic behavior in July 1962, which was strongly suspected to have arisen from radiation damage [8, p. 94].

As stated by Robert Baumann, the Ariel 1 US Project Manager: “Ariel started to malfunction on July 12, 1962. We on the project feel that this is not completely unrelated to the July 9, 1962 high altitude nuclear explosion.”

Ironically, one of the Ariel components that apparently suffered damage from Starfish Prime radiation was the kill switch that was designed to deactivate the spacecraft transmitter after 1.0 ± 0.1 years [3, p. 90]. This switch was intended to prevent the downlink frequency from being monopolized after the end of the useful mission; it is indicated by “one-year clock” on the upper right of the cutaway diagram below, taken from [9]. Without this timer acting Ariel 1 ended up operating (sporadically after September 1962) until November 1964, a total duration of 2.5 years [3, p. 90].

Ariel 1 cutaway view. (credit: K.W. Gatland) |

One further mission that was indirectly affected by Starfish Prime was the Mercury-Atlas 8 flight of astronaut Wally Schirra. This mission took place on October 3, 1962, by which time sounding rocket data showed that the radiation levels had decayed significantly. Even though it was felt that the flight was almost certainly safe, just in case the Mercury project installed [10, p. 432] one dosimeter on the hatch, attached four to the pilot’s pressure suit, and provided him with a handheld meter that provided real-time readings. Fortunately, no radiation issues were identified during the six-orbit flight.

Alouette 1, the second international satellite

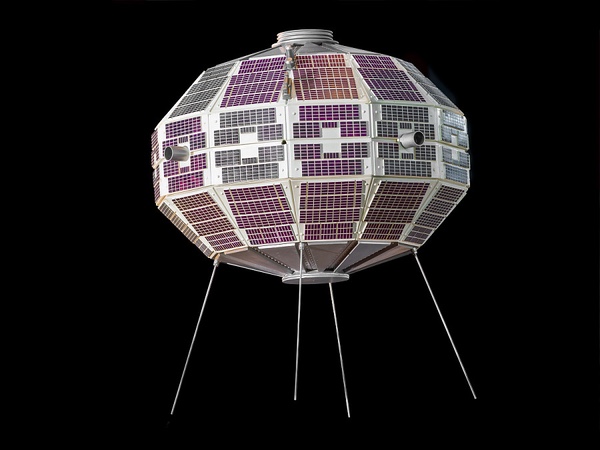

On September 29, 1962, five months after Ariel 1, the second international spacecraft was launched, this time from Vandenberg Air Force Base. This was Alouette 1, part of a joint Canadian/US project—again prompted by the US launch offer to COSPAR—to study the upper regions of the ionosphere of the Earth. The launch vehicle in this case was the Thor-Agena B, with a larger upper stage than that of the Thor-Delta. Alouette could consequently be somewhat more massive than Ariel, weighing 145.6 kilograms. The spacecraft was designed and constructed in Canada, led by the Defense Research Telecommunications Establishment (DRTE), with NASA providing launch and tracking; Goddard was responsible for NASA management. Alouette 2 was subsequently built from backup components, incorporating some improvements, and launched on November 29, 1965.

Alouette 1 Thor-Agena B launch vehicle. (credit: CRC Canada) |

The main instrument on each of these spacecraft was a “topside sounder” [11, pp. 49-51], designed to study the upper regions of the ionosphere by transmitting radio signals along the nadir direction. This allowed ionospheric parameters such as electron density, plasma temperature, and more to be measured at altitudes above that of the peak electron density, which typically occurs at 250 to 300 kilometers. This upper region contains the response of the ionosphere to disturbances such as geomagnetic storms, an understanding of which is important in applications such as communications and navigation. Alouette 1 was the first topside sounder: with its orbit of 996 by 1,032 kilometers at an inclination of 80.48 degrees, it could observe most of the ionosphere in the altitude range of 250 to 1,000 kilometers.

| An emphasis of Alouette design was simplicity, in order to encourage reliability. |

An emphasis of Alouette design was simplicity, in order to encourage reliability. One example of this was that the spacecraft were not equipped for on-board data storage, which at that time typically used failure-prone tape recorders. Instead, the satellite transmitted direct to a ground station when one was in view. In order to allow extensive data collection, a large network of stations (22 of these) was therefore required. The goal of spacecraft reliability was indeed achieved: in an era when a spacecraft lifetime of a year was notable, both Alouettes operated for ten years before intentionally being deactivated.

One unavoidable source of complexity was that, as a result of the radio frequencies needed to sound the ionosphere (1–12 megahertz [11, p. 50]), the spacecraft required the longest antennas that had yet been flown on any satellite: two had lengths of 150 feet (45.7 meters), and two were 75 feet (22.9 meters). These were made of slightly curved thin metal similar to a tape measure, initially wound around a drum, and deployed by the spin of the spacecraft once a brake on the drum was released. This design, known as a storable tubular extendible member (STEM), was developed by the SPAR Division of de Havilland Aircraft of Canada; derivatives have been widely used on many subsequent spacecraft.

SPAR later became Spar Aerospace and is now part of MDA. In a further example of international cooperation, it developed Canadarm for the Space Shuttle, Canadarm2 for the International Space Station, and Canadarm3 for the Lunar Gateway.

Alouette 1 was intended to remain spin stabilized throughout its mission. However, since its antennas were not perfectly rigid, as the satellite spun they flexed as first one side, then the other, was heated by the Sun. Solar radiation pressure acting on these deflected antennas produced a torque on the satellite in a mechanism that became known as “solar motoring.” [12, pp. 411-412] This caused the spin rate of Alouette 1 to gradually decrease from the original rate of about 1.5 rpm to essentially zero after three years. (Adding small plates perpendicular to the ends of the antennas on Alouette 2 reduced this despin effect considerably.) Once the spin rate became too low, the spacecraft ceased to be spin stabilized, instead taking up a “gravity gradient” orientation with the long antennas aligned with the local vertical. Fortunately, this attitude still allowed good science observations to be made.

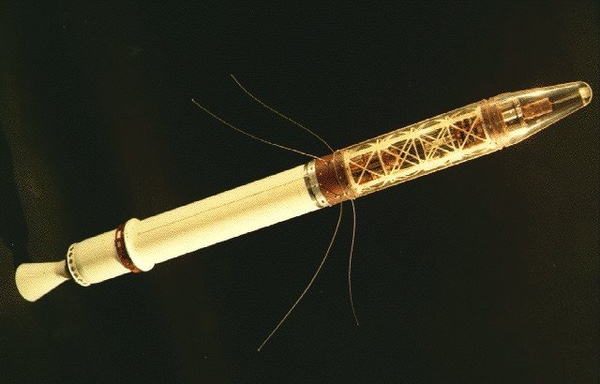

Alouette 1 central body; long horizontal antennas not shown. (credit: NASM) |

Alouette 1 was not the first spacecraft to behave quite differently to expectations once in space as a result of flexible elements, even though these were so light as to seem “obviously” negligible. In fact, this also occurred with the first US satellite, Explorer 1, although the mechanism was very different from solar motoring. This spacecraft had four short whip antennas protruding from its sides and was launched spinning about its long axis, with the expectation that this spin would persist. Instead, within one orbit the spacecraft entered a flat spin, end over end. This was initially a mystery but was subsequently shown by R.N. Bracewell and O.K. Garriott, in a paper [13] published less than eight months after the launch, to be caused by flexing of the wire booms as the satellite spins. This flexing leads to internal heating in the wires, dissipating energy as damping, and so driving the spacecraft towards its minimum energy state. For a slender (prolate) body like Explorer 1, this state can be shown to be an end-over-end tumble. This realization had a major effect on design choices for subsequent satellites: since any real spacecraft will exhibit some amount of damping somewhere within it, prolate spinners were to be avoided.

Explorer 1. (credit: NASA) |

One of the authors of this paper, Owen Garriott, later became a scientist-astronaut and flew on the Skylab 3 mission in 1973. While on Skylab, Garriott conducted a demonstration of the Explorer 1 mechanism by spinning a juice bottle about its long axis and observing it gradually transition into an end-over-end tumble [14, pp. 58-59]. In this case there were no antennas, but sloshing of the liquid in the bottle produced damping that was analogous, and had the same destabilizing effect. A bottle similar to the one used in this demonstration is visible at lower right in the photograph below. (During the mission Garriott was once videoed by Pilot Jack Lousma giving Commander Alan Bean a haircut. In his commentary, Lousma said: “…here is the distinguished professor Owen Garriott trimming his hair… You might wonder why we chose Owen to do this job… Well, we figured you could always trust a barber with a mustache.” [14, pp. 29, 31].)

Astronaut Owen Garriott having breakfast in the Skylab wardroom. (credit: NASA) |

As well as being the first international satellites, Ariel 1 and Aloutte 1 were among the first of many GSFC-related spacecraft to study the ionosphere and magnetosphere, including the series of Orbiting Geophysical Observatories (OGOs) and Interplanetary Monitoring Platforms (IMPs). This has proved to be a very active area for space research and remains so today: it represents one of NASA Goddard’s many lasting contributions to space science.

References

- History of British Space Science, H.S.W. Massey and M.O. Robins, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1986.

- Venture into Space: Early Years of Goddard Space Flight Center, A. Rosenthal, NASA Center History Series, 1968.

- Ariel 1: The First International Satellite – Experimental Results, NASA SP-119, 1966.

- Achieving Ariel II Design Compatibility, A.L. Franta and A.C. Davidson, NASA Technical Note D-3085, Apr. 1966.

- “Isle of Wight Aerospace: Flying Boats, Rocket Interceptors, Hovercraft and Launch Vehicles (All Briefly) – Part 2”, T. Williams, The Space Review, Sept. 30, 2024.

- “The STARFISH Exo-Atmospheric, High-Altitude Nuclear Weapons Test”, E.G. Stassinopoulos, Hardened Electronics and Radiation Technology Conference, Chantilly, VA, Apr. 22, 2015.

- “Did High-Altitude EMP Cause the Hawaiian Streetlight Incident?”, C.N. Vittitoe, Sandia National Laboratories, June 1989.

- The Ariel 1 Satellite, R.C. Baumann, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, Apr. 1963.

- Spacecraft and Boosters 2, K.W. Gatland, Iliffe Books, London, 1965.

- This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury, L.S. Swenson, J.M. Grimwood and C.C. Alexander, NASA SP-4201, The NASA Historical Series, 1966.

- Observation of the Earth and its Environment: Survey of Missions and Sensors, H.J. Kramer, 4th edition, Springer, Berlin, 2002.

- Spacecraft Attitude Dynamics, P.C. Hughes, Dover Publications, ***, 2004.

- “Rotation of Artificial Earth Satellites”, R.N. Bracewell and O.K. Garriott, Nature, Vol. 182, pp. 760-762, Sept. 20, 1958.

- A House in Space, H.S.F. Cooper, Jr., Angus & Robertson, London, 1977.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.