A hell of a character: the late, great, Martin Caidinby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Caidin was an author, screenwriter, and an authority on aviation. And he was also a bit of a weirdo. |

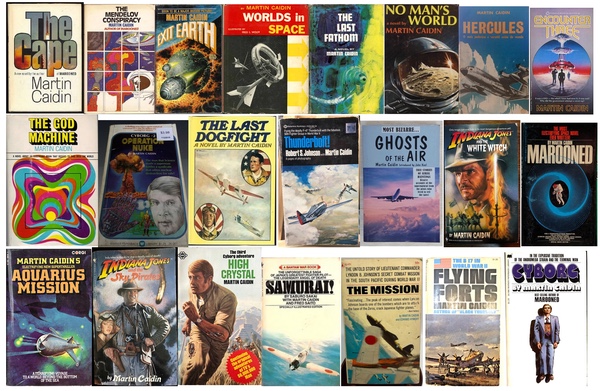

Martin Caidin was born in 1927 and died of thyroid cancer in 1997 at the age of 69, leaving behind a wife, two daughters, and three grandchildren. He began writing in the 1950s and then started writing fiction a few years later. He was one of those people who could crank out books and articles like a machine. He wrote more than 50 fiction and non-fiction books (one source claims as many as 80), and more than 1,000 magazine articles during his lifetime.

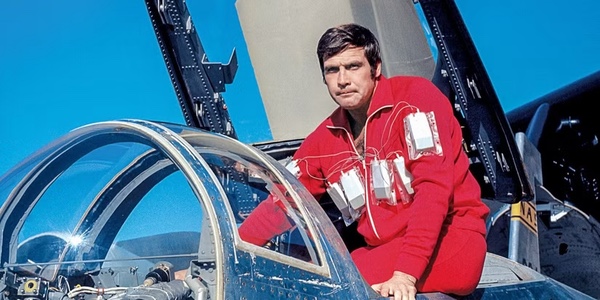

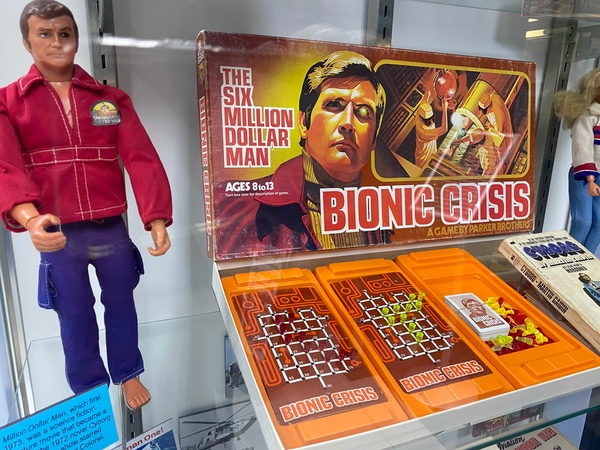

His most famous successful book was Cyborg, the novel that formed the basis of The Six Million Dollar Man television franchise. In some ways Caidin was typical of the authors who wrote for men’s magazines in the 1950s and 1960s, stories illustrated with shirtless heroes fighting off Nazis—or tigers—while a buxom damsel hid behind them. Caidin primarily wrote about flying, aviation and planes, spaceflight and astronauts, and current and near-term science fiction. He was nowhere near as talented as Norman Mailer or the other literary greats, but he was damn prolific.

Caidin was an author, screenwriter, and an authority on aviation. He was also a pilot and bought and restored a 1936 Junkers Ju 52 airplane. Later in life he became a talk show host. And he was also a bit of a weirdo.

Caidin's book Cyborg inspired the 1970s television show The Six-Million Dollar Man. (credit: Universal Television) |

Have typewriter, will fly

Martin Caidin was one of several authors, like Willy Ley, whose name became attached to the early space age because they were all over that topic. If you were looking for books on aviation and spaceflight in the 1960s, Caidin’s name appeared on the spines of many of them, and his articles popped up in many magazines. He lived near Cape Canaveral and wrote books about astronauts and pilots. He was for a while enamored of stories involving humans merged with machines and set in the present day.

Caidin’s writing career started in the mid-1950s with Jets, Rockets and Guided Missiles, and Rockets Beyond the Earth. In 1954 he published Worlds in Space. The book proposed a future of space exploration that included a space station and a colony on the Moon, as well as journeys to the planets. He did not think that a space station would be militarily useful and focused on its scientific value.

At that time, before there were real satellites, writing realistically about satellites was essentially writing science fiction. He knew he was speculating about spaceflight but acknowledged that it was hard not to speculate about a technology that was on the edge of literally taking off. Caidin’s book was reviewed by the New York Times, a major achievement by a young author.

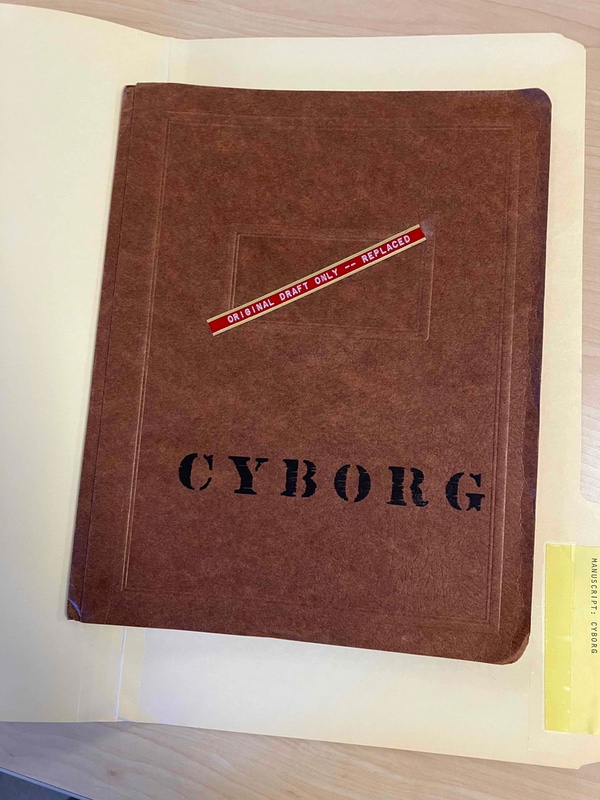

Caidin's original draft for his most popular book, Cyborg. (credit: author) |

Throughout the 1960s Caidin wrote non-fiction books, primarily about airplanes, and began to expand into fiction, including spaceflight. He wrote Cyborg in 1972, and within a year it became the basis of the television movie The Six Million Dollar Man. He wrote three sequels: Operation Nuke, High Crystal, and Cyborg IV. He reportedly witnessed the crash of the M2-F-2 lifting body aircraft that was featured at the beginning of the TV show.

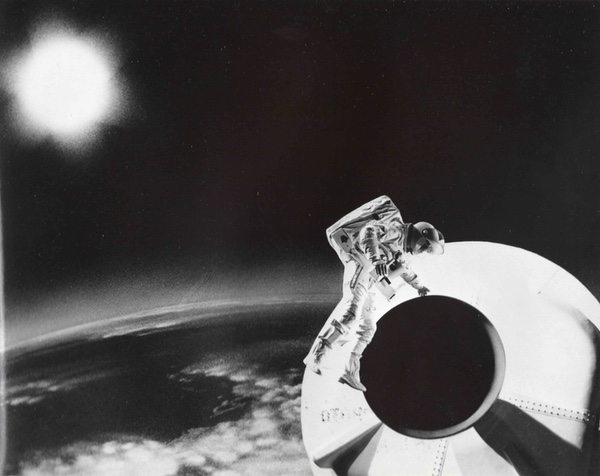

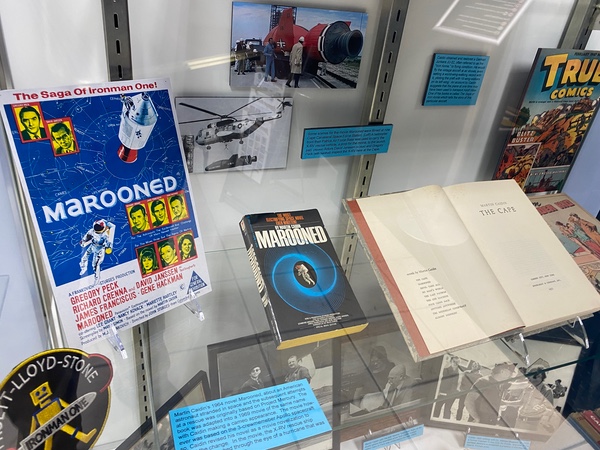

Caidin's book Marooned inspired a movie by the same name. (credit: Columbia Pictures) |

Astronauts were the protagonists in many of Caidin’s novels, although fully developed characters were not his forte. His 1964 novel Marooned was about American astronauts who become stranded in space and NASA's attempt to rescue them. In 1969, the book was adapted into a movie of the same name. Caidin also revised his earlier novel as a movie novelization, changing the focus from the Mercury program of the original to the then-current Apollo program.

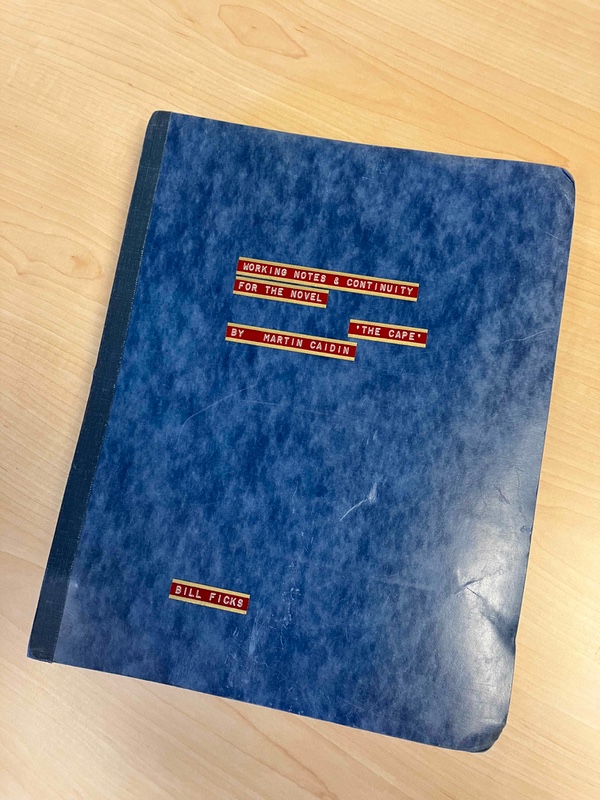

Notes for Caidin's manuscript The Cape, about saboteurs blowing up a Saturn V rocket in the Vehicle Assembly Building. (credit: Glen Swanson) |

Another 1970s Caidin novel, The Cape, featured terrorists blowing up a Saturn V rocket inside the giant Vehicle Assembly Building. Caidin knew that the rocket would not be fueled in the VAB, so he concocted a plot by which it was loaded with propellants when it went boom. Caidin also wrote a novel about the Soviets beating the United States to the Moon, and also Four Came Back, about a space station. He also wrote about artificial intelligence in the form of a supercomputer that seeks to take over the planet. One of his favorite books that he wrote was called Exit Earth, about a space ark leaving the Earth.

Caidin also played in other authors’ sandboxes. He wrote Buck Rogers: A Life in the Future, an adaptation of the pulp fiction and comic strip character, and an Indiana Jones tie-in novel. He wrote the movie novelization for The Final Countdown, about the then-new aircraft carrier USS Nimitz traveling back in time to just before the Pearl Harbor attack. (Nimitz is now being decommissioned.)

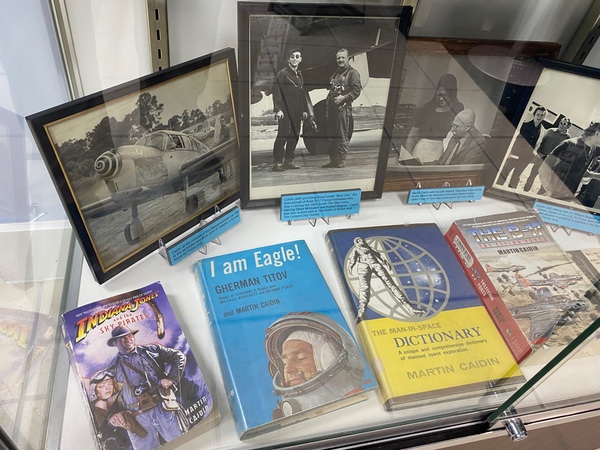

Although he was too young to serve in World War II, Caidin wrote many books about pilots and planes during the war, including Flying Forts, Thunderbolt!, and Fork-Tailed Devil: The P-38. He wrote a book about the C-130 Hercules, and helped write autobiographies, including cosmonaut Gherman Titov’s I Am Eagle!, and Saburo Sakai’s Samurai!. He also wrote the Man-In-Space Dictionary, Man Into Space, Vanguard!, Spaceport U.S.A., and Rendezvous in Space.

Caidin’s audience was male and he undoubtedly had a substantial teenage boy fandom enamored with his flying tales. He also worked to get young people into aviation.

Caidin was the author of at least fifty books on a wide variety of aviation and space subjects. (credit: author) |

The author has wings

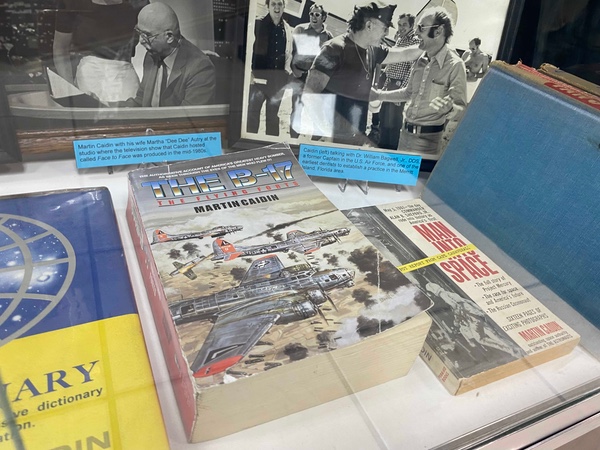

Caidin wasn’t just a writer: he had experience with many of the topics he wrote about. In 1961 he was one of the pilots of a formation flight of B-17s across the Atlantic Ocean. He turned that into a book called Everything But the Flak. He worked as a pilot for a movie and used his pilot connections to spend time in military aircraft.

| If he was alive today, Caidin would undoubtedly have a YouTube channel and a podcast. In the mid-1980s he hosted a confrontational television talk show. |

The biggest contributor to his reputation as a larger-than-life character was a pre-World War II German transport plane. Caidin bought and restored a Junkers Ju 52 aircraft and named it Iron Annie. In November 1981, Caidin was flying the plane when 19 people walked on one of its wings, setting a world record. In 1984, he sold Iron Annie to Lufthansa, which renamed it Tempelhof after a Berlin airport. The plane continues to fly for the airline for special flights. Of course, Caidin turned his experiences restoring the plane and flying it into several more books.

Moving things with his brain

In the 1970s, paranormal stories were popular and there was a mass market for books about UFOs, extraterrestrials, ghosts, Bigfoot, and the Bermuda Triangle. In 1975 Caidin wrote a Bermuda Triangle novel Three Corners To Nowhere. But although he was a purveyor of what some called “engineering fiction,” with a heavy emphasis on technology, Caidin also eventually claimed that he had telekinetic powers, and could move objects with his mind. Whether this was just Caidin telling tall tales for publicity, or if he truly believed he could do it, is unclear, but he refused to prove it to a public skeptic.

If he was alive today, Caidin would undoubtedly have a YouTube channel and a podcast. In the mid-1980s he hosted a confrontational television talk show. This was an emerging trend at the time, with CNN’s Crossfire, The Morton Downey Jr. Show in the late 1980s, and perfected by Jerry Springer in the 1990s. Caidin’s unique twist was that he went after far-right organizations such as the head of the Jewish Defense League, the head of the American Nazi Party, and other far-right spokespeople. These confrontational shows were a double-edged sword, however: Caidin was not just talking with people he disagreed with, he was giving fringe hate-mongers a platform to espouse their views when they would otherwise have trouble gaining media attention. A spokesman for the Aryan Nations hate group would almost never be able to get on television unless he was arrested, but Caidin gave him airtime. That issue is current in today’s politics, but a major difference is that today it is much easier for fringe characters to reach mass audiences than it was when Caidin hosted his show.

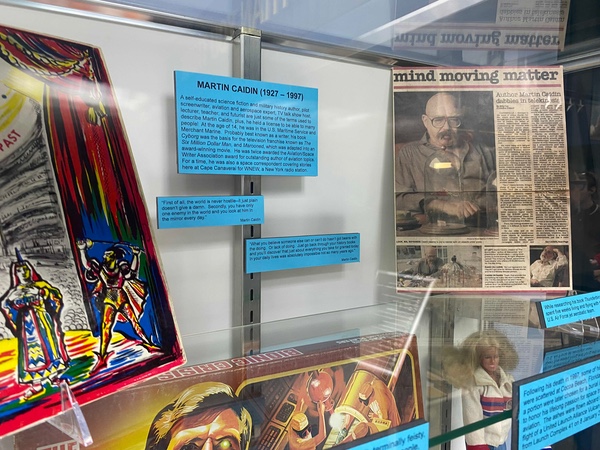

The Sands Space History Center in Florida currently has a display about Martin Caidin, who lived nearby and regularly wrote about about aviation and space subjects, both fiction and non-fiction. (credit: Dwayne Day) |

Have cigar, will travel

Martin Caidin was known for haunting the bars and hangars around Cape Canaveral—he met his fourth wife, Dee-Dee, when she came up to him in his regular booth in the famed Bernard’s Surf bar in Cocoa Beach to argue with him about the ending of one of his books. But nobody has fully chronicled the story of the man himself. How did he treat his family and friends? He was prolific, but what did his editors think of him? Did he miss deadlines, bounce checks, tell lewd jokes? How much of his public persona was real vs. invented? How many of his non-fiction stories were true vs. exaggerations to sell books? Hopefully, the upcoming documentary will shed more light on him.

The Sands Space History Center display is small and devoted primarily to his works rather than the man. But hopefully it may inspire somebody to dig deeper about the crazy, cigar-chomping guy who wrote about spaceflight and aviation in the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s, and flew a German transport plane with people walking on the wing.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.