Much needed cargo for the Moonby Ajay Kothari

|

| A large amount of infrastructure—hundreds of tons—will be needed on the lunar surface for a sustainable presence. This is a glaring deficit in the plan. |

While there has been interest in getting humans back to the Moon before China, by 2028 to 2030, the real competition is not for that anymore. It is for establishing permanence on Moon with habitats—the outposts.

It is not about a “guided tour”, a sightseeing tour taking pictures or flag planting. It is about buying land and building a house to live there, as we do on Earth, even for short stints at a time. That is a much bigger deal.

A large amount of infrastructure—hundreds of tons—will be needed on the lunar surface for a sustainable presence. Recent Congressional action funds missions up to Artemis 5 but not the infrastructure needed for a permanent presence, which is indispensable. This is a glaring deficit in the plan.

Some argue that we already beat China and every other country to the Moon by 60 years. True, but not for establishing a permanent presence with habitats. That is still open, unclaimed. That is still to be done. China will likely beat us in that competition unless we do something in next two to three years.

This proposed method here may be the least costly and safest option, with margins, and also the quickest method to supplement the plans and alleviate this deficit. For Artemis 3 and beyond, one of the two options would be to use Falcon Heavy as an add-on to SLS plans, a proven vehicle with 11 successful flights. Other possibilities include New Glenn and possibly Rocket Lab’s Neutron when successfully and reliably flown, which would likely be too late for this urgent need to compete with International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) of China and Russia by 2030.

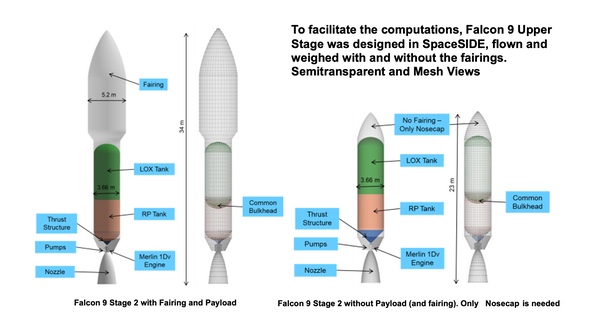

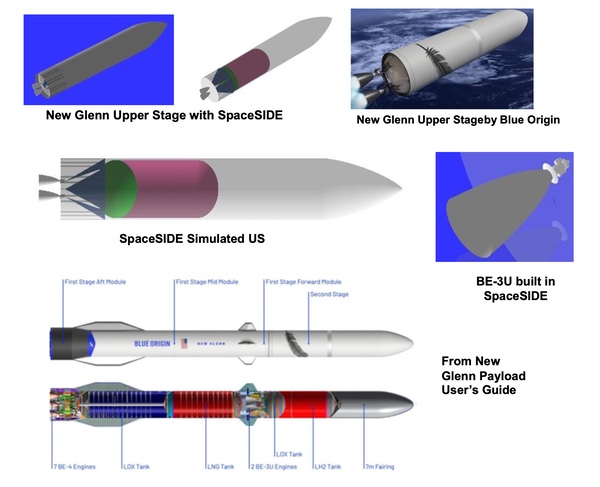

The primary requirements for facilitating this option are to have a reusable first (or booster) stage and a low-dry-weight upper stage (or orbiter stage). The former will reduce the cost of the mission and the latter will reduce the mass needed for translunar injection (TLI), lunar orbit insertion (LOI), and landing propellant. Propellant refueling would reduce the total dry weight in LEO but it comes with unproven cryogenic propellant transfer, which is not wise. Both the SpaceX Falcon Heavy and Blue Origin’s New Glenn offer those possibilities with their upper stages at 4.5–6 tons and 10–12 tons respectively. Starship does not, with its upper stage at nearly 85–100 tons. To realize this, the upper stages of both were recreated in our code SpaceSIDE. They are shown below.

| here is no need to redevelop new rockets such as Starship or SLS for new aims except in specific cases. This approach will build a railroad to space with many stops. |

The computed numbers below prove that this is quite feasible with margins to spare. The idea would be to use four flights of Falcon Heavy, docking the upper stages in LEO and thus increase the propellant fraction to be able to do TLI, LOI, and lunar landing. There is no refueling need and no need to have a stopover in near-rectilinear halo orbit (NRHO). The concept is direct to Moon. Docking in LEO has been done continuously since 1966 and numerous times at ISS. It is simpler than docking at ISS, not requiring human transfer or propellant transfer either, and can be designed much more simply than the refueling options. So compared to the present scenarios of 10–20 refuelings of methane and liquid oxygen required by SpaceX’s HLS or the liquid oxygen and liquid hydrogen refuelings of New Glenn at LEO and NRHO, this would be easier to accomplish.

This approach is also suggested for many of our future missions within the solar system in addition to the ones in the pipeline such as SLS, Starship, and New Glenn. The combination/permutation with five degrees of freedom (number of flights, number of docckings/refueling, payload sizes, and delta-v needed for different destinations) provide hundreds of possible solutions with already developed rockets and engines. There is no need to redevelop new rockets such as Starship or SLS for new aims except in specific cases. This approach will build a railroad to space with many stops. This analysis did not use the refueling option, so the number of degrees of freedom here is four.

Since the above options are for cargo delivery only, no consideration is given to flying up to low lunar orbit from the lunar surface and/or back to Earth (trans-Earth injection).

Propellant Fractions (PF) are calculated for each fuel/oxidizer combination

| ISP | g | DeltaV | PF | LH2 | CH4 | RP | LOX | Mass Ratio | |

| sec | m/s2 | m/s | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | kg/m3 | |||

| HydroLOX | 460 | 9.81 | 6210 | 0.7475 | 68 | 1153 | 5.9 | ||

| MethLOX | 380 | 9.81 | 6210 | 0.811 | 423 | 1153 | 3.6 | ||

| RPLOX | 348 | 9.81 | 6210 | 0.8378 | 805 | 1153 | 2.6 |

The Falcon Heavy option

The Falcon Heavy LEO payload is 38, 54, or 63 tons depending on fully reusable, partially reusable (the side boosters land and can be reused with the core expended), and fully expendable. This analysis picked PR option.

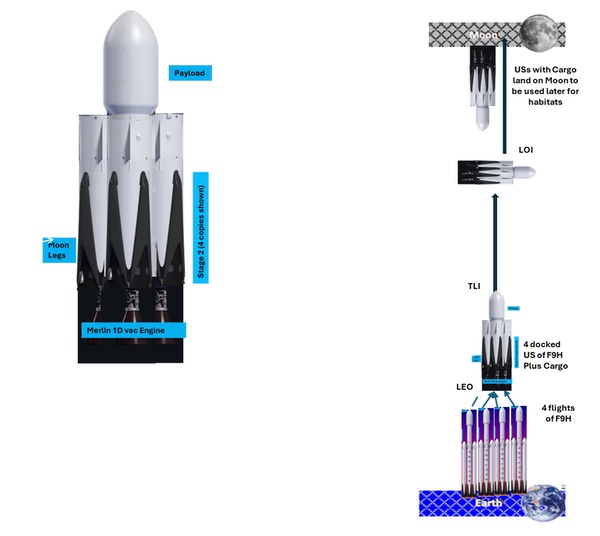

The first Falcon Heavy flight carries the payload (~15 tons) while the three additional upper stages from the subsequent Falcon Heavy launches would carry that much (54 tons) extra propellant each, which will remain in them at LEO. They dock at 120 deg each to the payload carrying upper stage as shown below.

Thus the payload fraction is increased to what is required (~0.84 for Merlin1Dv engine) for TLI plus LOI plus landing (3260+900+2050 meters per second) for the combination.

The outer 3 upper stages fire their Merlin 1Dv rockets for TLI and LOI. The central stage rocket then is used to land the combination on Lunar surface with throttling as needed.

|

Four Flights of Falcon Heavy (F9H) w RP/LOX US

| Prop Fraction (PF) Required | 0.838 | ||

| Upper Stage | RP/LOX | ||

| tons | Actual | Prop | |

| Payload Capacity | 54.4 | 15 | 39.4000 |

| Dry Weight | 6 | # Mated | |

| # flights | 4 | 4 | |

| Gross in LEO | Propellant | PF | |

| Mated | 241.6 | 202.6 | 0.8386 |

The Falcon 9 upper stage is 4.5 tons according to SpaceX numbers. Here we allow another 1.5 tons to rigidize the tanks (in case we aim to use them at some stage as temporary habitation for astronauts), additional mass for landing legs, and docking mechanisms. So dry weight of 6 t is used in the analysis.

|

Cost savings: Four Falcon Heavy launches, at $120 million each, would cost $480 million. If SLS is used via NRHO, it would cost about $2 billion (the NASA Inspector General estimate, which does not include Orion.) The cost for all included is about $4 billion for each flight. The result is substantial cost savings to NASA: almost 88%, rounded off here to 80%. It makes no sense to attempt to use SLS for cargo.

New Glenn upper stage built in SpaceSIDE

The New Glenn upper stage was built in Astrox’s SpaceSIDE. No weights—dry, gross liftoff weight or of various subsystems—were available from Blue Origin for the upper stage or the booster stage. Only payloads to LEO (45 tons) and GTO were available. Based on these, an attempt was made to replicate the payload numbers using SpaceSIDE’s component-based subsystem equations to build the upper stage. The BE-3U engine was also designed in SpaceSIDE for the expander cycle used, which yielded a specific impulse (Isp) of 463.5 seconds. Liquid hydrogen density of 68 kilograms per cubic meter and LOX of 1,153 kilograms per cubic meter was used. The upper stage was flown from staging to 250-kilometer altitude at 51.6-degree inclination (New Glenn’s payload users guide says more than 200-kilometer altitude) for LEO.

|

New Glenn Upper Stage Weight Breakdown

| staging at 7700 f/s | BE-3U | |||

| Upper Stage (kg) | Total (kg) | S2 Fractions w payload | S2 Fractions w/o payload | |

| GTOW | 201,031 | 201,031 | ||

| PropUsed | 143,380 | 143,380 | 71.32% | 91.89% |

| startup | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| unusable | 717 | 717 | 0.36% | 0.46% |

| reserve | 1,434 | 1,434 | 0.71% | 0.92% |

| EmptyWeight | 10,500 | 10,500 | 5.22% | 6.73% |

| Payload | 45,000 | 45,000 | 22.38% | |

| GTOW | 201,031 | 201,031 | 100.00% | 100.00% |

| Ejected | 12,651 | 12,651 | ||

| Length (m) | 41.5000 | |||

| Diameter (m) | 7.0000 |

With New Glenn first stage as the booster, we have multiple permutations available with four degrees of freedom: payload size, number of flights, delta-v needed, and the number mated in orbit. This allows us to reach different possible solutions depending on need and cost. The BE-3U engine is used for all the options below.

New Glenn with LH2/LOX US to Moon Surface

| Prop Fraction (PF) Required | 0.747 | ||

| Upper Stage | LH2/LOX | ||

| tons | Actual | Prop | |

| Payload Capacity | 45 | 14 | 31.0000 |

| Dry Weight | 10.5 | # Mated | |

| # flights | 4 | 4 | |

| Gross in LEO | Propellant | PF | |

| Mated | 222 | 166 | 0.7477 |

The operations for New Glenn option are the same as described for Falcon Heavy.

Cost savings: The cost for a New Glenn flight has not been stated by Blue. Media estimates are in the same neighborhood as Falcon Heavy partially-reused option used above. Taking average of the media estimates of $160 million per flight, four launches yields $640 million. Again, a substantial cost savings to NASA compared to SLS: almost 84%, rounded down here to 75%. It makes no sense to attempt to use SLS for cargo.

Thus, both Falcon Heavy and New Glenn for moving cargo seem quite competitive, offer substantial savings, and possibly a quicker implementation. Starship is not available today but even when it becomes available, it will have the same refueling and fineness ratio problems that will not go away with success. For HLS, SpaceX needs to redesign and downsize (by about one third) the Starship upper stage, which may solve many problems, but this has not been mentioned by SpaceX.

This approach can be used for many of our future missions within the solar system in addition to the ones in the pipeline already. It offers hundreds of possible solutions with already developed rockets and engines. This approach will build a railroad to the solar system with many stops, just as we did 150 years ago with the railroad to the West and 50 years ago with Interstate highways.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.