Breaking dishes: the space facility at Yevpatoriyaby Dwayne A. Day

|

| The facility was intended to support Soviet lunar and planetary missions, and the Soviet government did not keep it secret. Soviet publications about the facility were used by the CIA to piece together clues as to what was happening there. |

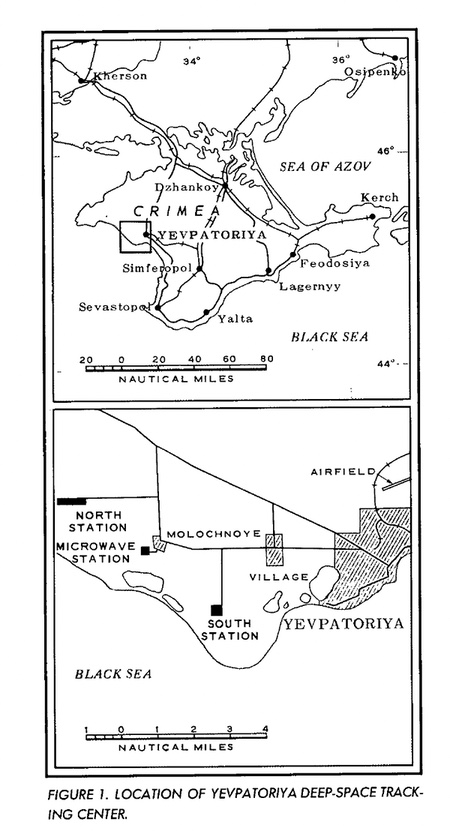

What the Russians are currently doing there, and why the Ukrainians have attacked the equipment there, is unknown. But Yevpatoriya, and a nearby facility at Simferopol, also on the Crimean peninsula, played an important but enigmatic role in the Cold War, and both were a major target for United States intelligence agencies. (Note: there are different spellings of Yevpatoriya and the author has chosen to use the one most commonly—but not always—used by the CIA during the Cold War.)

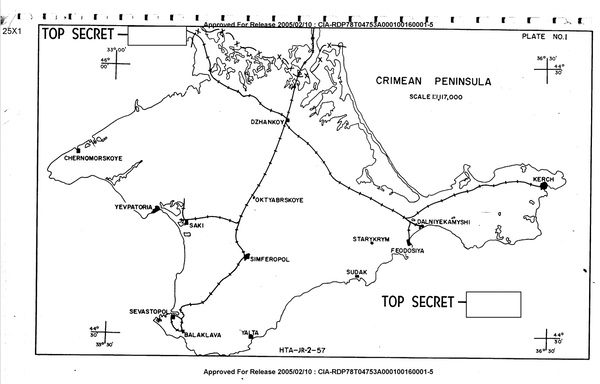

A 1957 CIA map of Crimea. Note both Yevpatoriya and Simferopol, which later became important space tracking stations. (credit: CIA) |

Like something from a James Bond film

It does not appear that Yevpatoriya was of particular interest to the CIA during the early years of the Cold War. As a small city in western Crimea, the CIA was aware of it and its potential importance in the control of the Black Sea, but there were other locations of greater interest, particularly seaports. In November 1956, an attempt to search for evidence of an anti-ship missile proving ground near Yevpatoriya was made using a U-2 reconnaissance aircraft, but cloud cover prevented interpretation of photography over the area.

In summer 1957, a U-2 flew around the Crimean peninsula and photographed many military installations, notably many warships both at anchor and underway. A known airfield at Yevpatoriya was not able to be photographed due to cloud cover and it being far from the aircraft’s path. In September, the CIA produced a detailed report about military installations on Crimea, notably many warships both at anchor and underway.

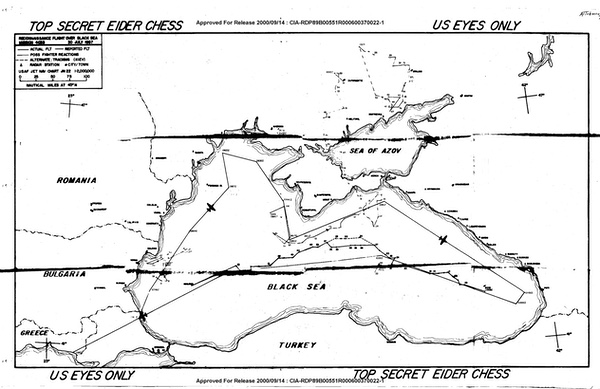

In summer 1957, a U-2 reconnaissance plane flown by a CIA pilot flew over the Black Sea and photographed targets inside Crimea. During this mission, Yevpatoriya was obscured by clouds. (credit: CIA) |

Starting in 1960, the Soviets began construction of a major satellite tracking station only a few kilometers from Yevpatoriya. The main construction was apparently finished by 1961. The facility was intended to support Soviet lunar and planetary missions, and the Soviet government did not keep it secret. Soviet publications about the facility were used by the CIA to piece together clues as to what was happening there.

| It looked like something from The Thunderbirds, or a James Bond movie—nothing like it existed in other space programs. |

In 1963, the Soviet newspaper Komsomol’skaya Pravda published an article titled “Attention! The Automatic Interplanetary Station is Calling…” which referred to the tracking station at Yevpatoriya and its role in Soviet planetary programs, and even published a photograph of the facility.

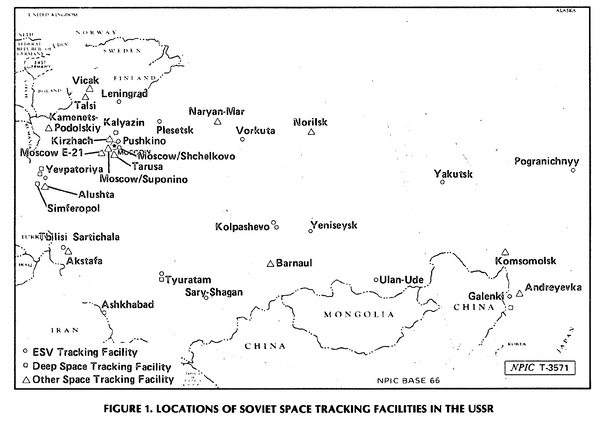

This 1982 map shows the location of the many satellite tracking stations throughout the Soviet Union. There were only a few stations used for communicating with lunar and planetary missions. (credit: CIA) |

Equally important, at the invitation of the Soviet Union, Sir Bernard Lovell, who was then the director of the United Kingdom’s famed Jodrell Bank Observatory, visited the Yevpatoriya facility in 1963. Lovell had developed good relations with the Soviet space science community and had even helped them with their space missions. His visit was unprecedented, and Lovell described it in a July 1963 article for New Scientist. “As few Russians have been able to visit the place, I felt very privileged at being the first Westerner to go there,” he wrote. “The primary purpose of the station, and the reason for its existence, is the tracking of lunar and planetary probes; it was from here that the abortive Venus and Mars probes were commanded. It belongs to the Institute of Radiotechnics and Electronics, directed by Academician V.a. Kotelnikov,” Lovell stated.

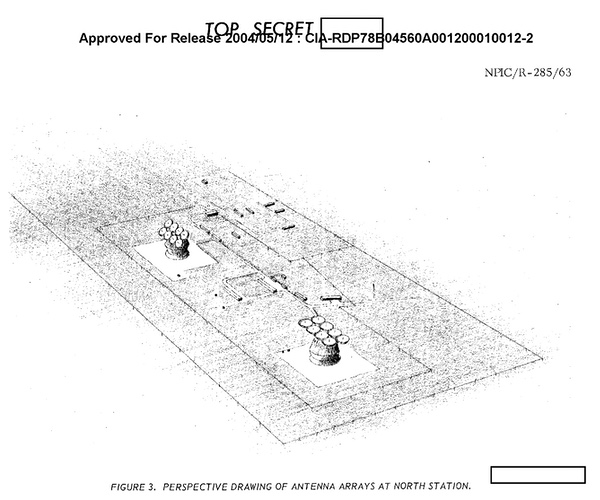

The north facility at Yevpatoriya had two large satellite dish arrays. The south facility had only one of these antenna arrays. The Soviet Union released photos of the antennas, and in 1963 Sir Bernard Lovell was able to visit Yevpatoriya. (credit: CIA) |

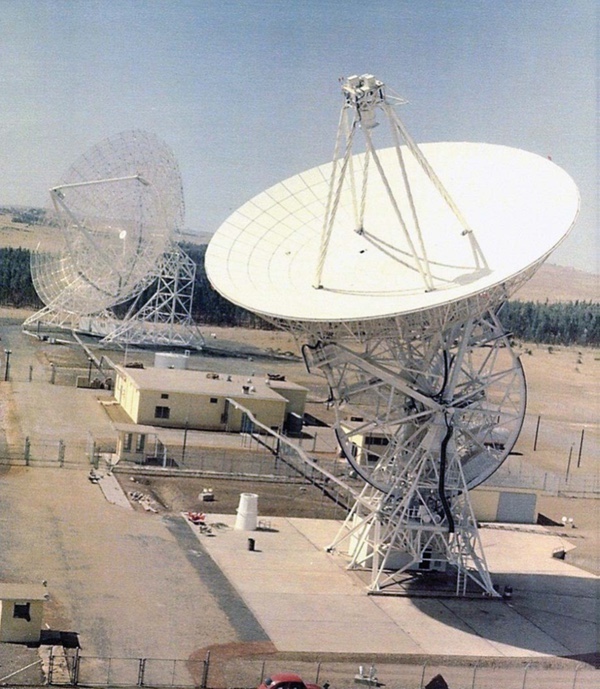

Lovell mentioned the huge tracking dishes the Soviets had built at the location, eight large dishes mounted on a single rotating rectangular mount. It looked like something from The Thunderbirds, or a James Bond movie—nothing like it existed in other space programs. The Soviets released photographs of the tracking antennas which appeared in books in the West, adding to the mystique of the Soviet space program. Whereas Jodrell Bank in England with its big impressive dish in the countryside became iconic in its own way, the unique communications system at Yevpatoriya also came to symbolize the often secretive Soviet space effort.

The locations of the three Yevpatoriya facilities as depicted in an early CIA map. The microwave station would eventually become the site of the large 70-meter dish. (credit: CIA) |

Yevpatoriya grows

Starting in 1960, American satellites overflew Crimea and photographed the facilities there. The United States was fully aware of what the Soviets were doing, although initial photographs were low quality. In September 1963, for unknown reasons, the National Security Agency, which was responsible for intercepting Soviet radio signals, requested that the National Photographic Interpretation Center (NPIC), which analyzed reconnaissance photos, conduct a survey of the area near Ust Ukhta in the northern Soviet Union for a deep-space tracking or communications facility. NPIC surveyed the area for a 50-nautical-mile (93-kilometer) radius and found nothing.

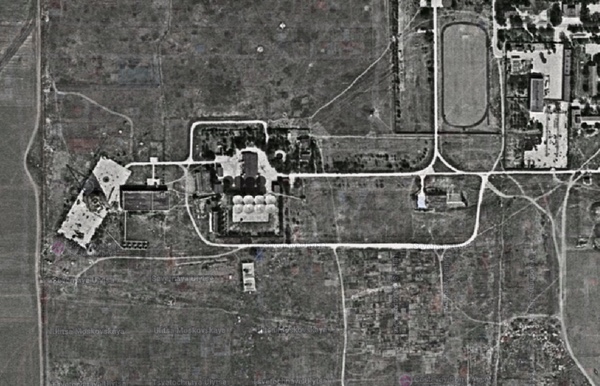

Yevpatoriya was divided into three facilities, which the CIA designated North, Central, and South. The north station was used for receiving signals and was separated from the south station, which was used for transmission, to avoid interference. Multiple antennas and satellite dishes were at the northern site, including two large eight-dish antenna array clusters. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

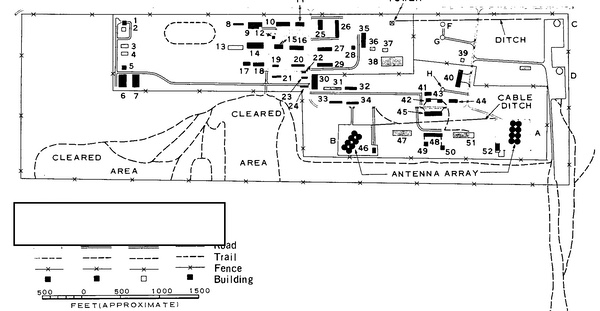

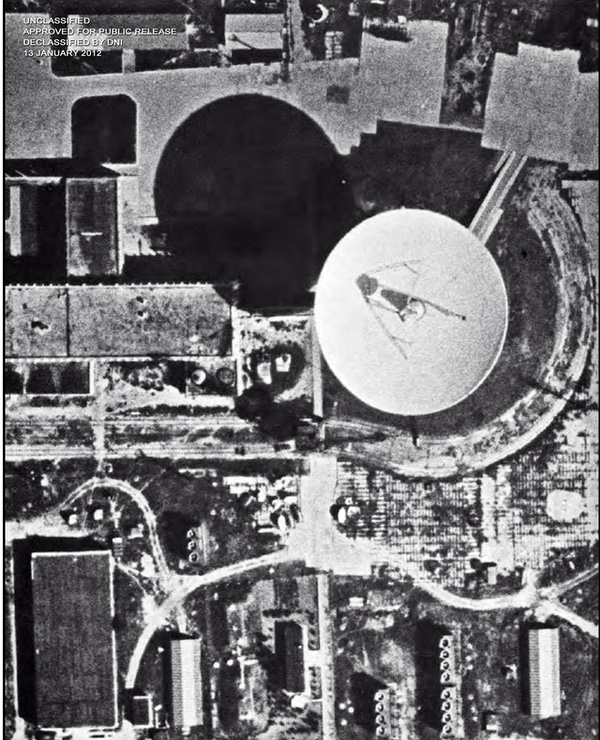

By November 1963, NPIC created a report: “Deep-Space Probe Tracking and Communication Center, Yevpatoriya, USSR.” As NPIC described it, the center consisted of two tracking stations, then designated “North” and “South,” and a microwave station for ground communications.

The north station was divided by security fences into three sections: a “celestial communication section,” as the report called it, a support section, and a probable terrestrial communication section. The celestial communication section contained two steerable antenna arrays located 600 meters apart, two possible amplifier buildings, and nine miscellaneous control and/or laboratory buildings. Each steerable antenna array consisted of eight 16-meter solid, circular parabolic reflectors arranged in two rows of four reflectors each. The probable terrestrial communication section consisted of a large area of grassland that probably contained high-frequency receiving antennas, but they could not be identified given existing sources.

A 1963 CIA map of the north Yevpatoriya facility produced from satellite photos. Photo-interpreters kept close watch for any new construction at the facilities. (credit: CIA) |

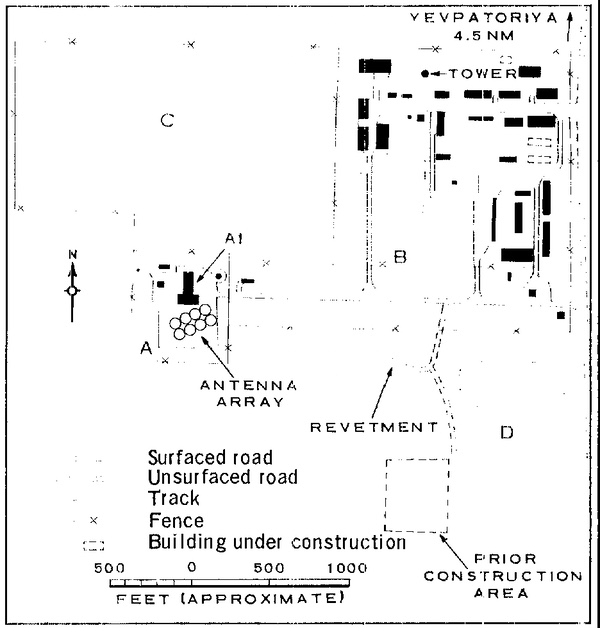

The south station consisted of four main sections: a celestial communication section, a support section, a probable terrestrial communication section, and a possible antenna array section. The celestial communication section contained a steerable antenna array identical, or nearly so, to the two arrays at the north station. The array was believed to be the transmitter for communication with deep space missions, and the arrays at the north station were the receivers. The support section had four barracks-type buildings capable of holding 200-300 personnel. Satellite photos also indicated that a possible antenna array section may have started construction but then been abandoned.

One of the unique antenna arrays at the northern Yevpatoria facility. From the ground, particularly when pointed at a low azimuth, they look like something from a movie. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

The microwave station was located midway between the two stations. It consisted of a control building and a lattice tower approximately 240 feet (73 meters) high supporting two microwave dishes. They appeared to be oriented in the general direction of Simferopol. A wire line connected the station to north station.

The satellite antenna array at the south Yevpatoriya facility. This was used for transmitting. This antenna has since been demolished. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

Yevpatoriya was not the only place with the large antenna arrays. A CORONA reconnaissance satellite mission photographed identical eight-dish antenna arrays, with smaller diameter dishes, that had been built at the Serpukhov Radio Physical Station by August 1964.

By October 1965, continuing review of CORONA satellite mission 1024-1 photographs revealed new construction at Yevpatoriya. By August 1966, the CIA’s Imagery Analysis Division had produced a detailed chronology of the development of the facilities there. New construction was underway at the electronic facilities at the north station. The CIA conducted detailed measurements of all of the buildings at both sites.

The south facility at Yevpatoriya was not as extensive as the northern facility, but it did include large bunkers to house hundreds of personnel. (credit: CIA) |

In August 1966, CORONA mission 1036-1 identified a new steerable parabolic dish at Yevpatoriya. Although no new multi-dish arrays were built, other communications equipment was later added at the locations, and the US intelligence community kept track of the facilities. In January 1970, photography revealed an excavation for a possible second large space tracking antenna at Yevpatoriya south. By this time, the north facility already contained five large antennas. A large rectangular excavation was dug about a kilometer and a half from the existing eight-dish antenna array. It was of the same approximate size as the existing eight-dish antenna. An antenna at that location would, “like the existing antenna, have an unobstructed look-angle for acquisition of spacecraft to the south and east.” However, no new eight-dish antenna array was built.

| The report indicated that Simferopol was now “apparently the most significant tracking facility in the Soviet Union,” containing “the largest number of antennas, the largest area, and the most personnel of any of the Soviet tracking facilities.” |

By the early 1970s, the central facility, which up to this time had been a microwave communications center, was the site of a major new construction. The Soviets built a huge, 70-meter diameter satellite dish, equivalent to the largest satellite communications dishes built by NASA. It was designated as RT-70, and could also be used as a radio telescope. This dish was used for collecting very faint signals from more distant spacecraft and was equivalent to NASA’s three large 70-meter dishes constructed during the early 1960s in California, Spain, and Australia.

The Soviet government referred to the Yevpatoriya facilities as NIP-16. The Soviets designated the north site as site 1, the south site as site 2, and the central site as site 3. Site number 1 is near Vitino, site number 2 is near Zaozyornoe, and site number 3, which was the last to be constructed, is near Molochnoe.

The satellite antenna array at the south Yevpatoriya facility. This was part of the Pluton network. It has been demolished. (credit: Wikimedia Commons) |

Although the US intelligence community may not have known it for decades, the eight-dish array antennas were designated ADU-1000 by the Russians and formed the Pluton (“Pluto”) deep space tracking network. The southern transmitting array and northern receiving arrays were separated from each other to ensure that the transmitting antenna did not interfere with the receiving antennas. The 70-meter dish at the central site was designated as RT-70 by the Russians and became operational in the 1970s when it apparently began to take over most of the functions of the ADU-1000 antennas. NIP-16 also served as the mission control center for Soviet manned space missions until the mid-1970s.

Simferopol was the site of a large dish used to receive signals from Soviet Mars and lunar missions. Its operations were connected by the CIA to the Yevpatoriya facility to the northwest. (credit: NRO) |

Simferopol

Yevpatoriya was not the only space communications facility on Crimea. It is unclear when the US intelligence community first gathered hard data on the existence of a space tracking and communications facility at Simferopol, 28 nautical miles (52 kilometers) southeast of the south station of Yevpatoriya. But in September 1963, recent satellite and ground photography identified a large parabolic antenna about 26 meters in diameter at Simferopol.

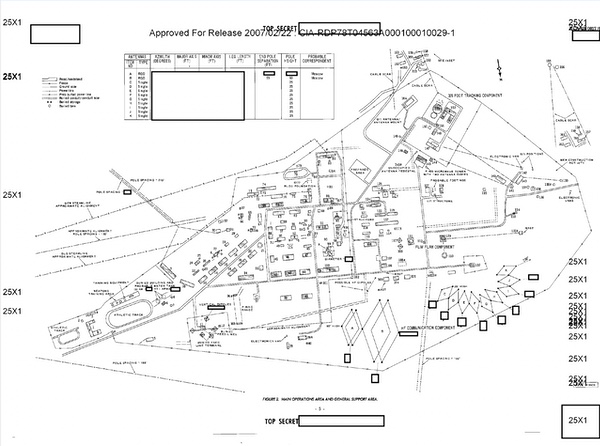

Simferopol eventually became a large space tracking and communications station that was closely monitored by the US intelligence community. It is depicted here in a declassified 1969 map. (credit: CIA) |

In November 1962, Komsomol’skaya Pravda discussed the Mars 1 mission and the Yevpatoriya station. Pravda discussed the Lunik 4 tracking operation in April 1963. Both articles indirectly referred to a large dish antenna, which was likely a dish located at the Simferopol station. They also mentioned the frequency used for communicating with the planetary spacecraft. Based upon Soviet statements about the Mars 1 and Lunik 4 missions, the US intelligence community believed that the Simferopol dish was connected to those missions, and concluded that radio or radar astronomy were not its primary missions.

Although Yevpatoriya was the first deep space tracking facility in Crimea, it was soon joined by Simferopol, also on the peninsula. By the late 1960s, the CIA determined that Simferopol was the most extensive satellite and space tracking facility in the Soviet Union. It was also used to eavesdrop on the Apollo missions. This satellite photo was taken in 1972. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

Over the next few years, Simferopol grew substantially. In June 1969, NPIC produced a detailed overview of the Simferopol Space Flight Center. The report indicated that it was now “apparently the most significant tracking facility in the Soviet Union,” containing “the largest number of antennas, the largest area, and the most personnel of any of the Soviet tracking facilities.” It was one of a network of ten facilities containing satellite vehicle tracking equipment and providing command and control for Soviet near-space events. It also supported lunar programs “associated with the Yevpatroriya Deep Space Tracking Facility.”

Simferopol continued to grow and is seen here in 1983. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

A dish at Simferopol photographed by an American reconnaissance satellite in 1983. (credit: Harry Stranger) |

Simferopol could be divided into four functional areas: the operations area, telemetry collection area, interferometer area, and the general support area. A major portion of the facility was the “Flim Flam component,” which consisted of two control buildings with roof-mounted environmental domes covering tracking and receiving dishes. Other Flim Flam components were located at other tracking facilities, and they provided the main method of communicating with Soviet spacecraft in Earth orbit. It is unclear if the US intelligence community was aware that the big dish at Simferopol had been used by the Soviets to eavesdrop on Apollo missions to the Moon. (See “The satellite eavesdropping stations of Russia’s intelligence services (part 1),” The Space Review, January 20, 2025, and part 2, January 27, 2025.)

The STONEHOUSE facility in Ethiopia was operated by the National Security Agency until 1974 and used to eavesdrop on communications sent from spacecraft down to the Yevpatoriya and Simferopol ground stations. (credit: NSA) |

BANKHEAD and STONEHOUSE

The US intelligence community began an effort in the early 1960s to intercept communications to and from Yevpatoriya space tracking and communications station and later the Simferopol station. Transmissions from Yevpatoriya to space could be intercepted at an American listening post in Turkey initially named BANKHEAD. But any signals coming down to Earth from distant spacecraft, such as lunar and Mars probes, would be very low power and require a large dish to collect them.

| The NSA’s STONEHOUSE facility was apparently able to collect higher quality signals than the Soviets could with their equipment at Yevpatoriya. |

In the early 1960s, the United States began considering building three large interception dishes at three different locations around the world to collect signals from Soviet planetary spacecraft. They were to be named STONEHOUSE. The Americans expected that the Soviets would have three deep space ground stations around the world, and STONEHOUSE stations would be required for each of them (see “Stonehouse: Deep space listening in the high desert,” The Space Review, May 8, 2023 and “Stealing secrets from the ether: missile and satellite telemetry interception during the Cold War,” The Space Review, January 17, 2022.)

The National Security Agency, which prepared to build the STONEHOUSE dishes, eliminated two of the three stations due to cost. But it caught a break when the Soviets decided to not build additional ground stations and only transmit during the time when the spacecraft was in view of the Crimean station—the so-called “dump method.” Thus, only one STONEHOUSE interception station was needed.

A deep space interception station required a large antenna, a highly sensitive receiver, and high-quality recording devices. It also ideally needed to be sited in a location free of radio noise. The single STONEHOUSE station was built in Ethiopia starting in 1963, and in 1964 the Department of Defense released a cover story that it was an electronics research facility.

The BANKHEAD system in Turkey, which was eventually renamed HIPPODROME, which could intercept signals going up to space, was apparently tasked with cueing STONEHOUSE about Soviet planetary launches so that STONEHOUSE could later intercept their data.

The original STONEHOUSE plan was a single 26-meter (85-foot) diameter antenna, but a 46-meter (150-foot) diameter antenna was later added for redundancy. The larger antenna had lower surface quality but simpler construction. Jodrell Bank’s huge dish in the United Kingdom, although not ideally suited for intercepting Soviet deep space communications, was also used for that purpose—Sir Bernard Lovell, although friendly with Soviet scientists, was also British to the core.

The NSA’s STONEHOUSE facility was apparently able to collect higher quality signals than the Soviets could with their equipment at Yevpatoriya. In 1974, the STONEHOUSE facility was closed due to a civil war in Ethiopia, and the NSA apparently moved operations to a British facility in Cyprus, which had the benefit of being closer to Yevpatoriya and Simferopol.

Although the CIA’s interest in Soviet planetary missions decreased during the 1970s, Yevpatoriya and Simferopol were also used to communicate with high-altitude Soviet communications satellites, so they remained important targets for intelligence collection.

By early 1982, Yevpatoriya’s north facility had been updated with newer equipment. The north area consisted of 24 different antennas, including two 12-meter diameter ORBITA antennas, an 8-meter diameter antenna, two 25-meter diameter antennas, the two famous eight-dish antenna arrays, a four-element telemetry antenna, a QUAD LEAF antenna, and several others. The central facility contained the huge 70-meter-diameter antenna, a large antenna control building, and ten support buildings.

| Why Ukraine attacked Yevpatoriya is confusing. They apparently believe that the 3762/4 observatory and the big RT-70 dish are associated with the GLONASS navigation system. |

The south facility included four double rhombic antennas, two horizontal dipole antennas, a 16-element telemetry antenna, the eight-dish antenna array, a new 32-meter diameter antenna, and two mast antennas. The facility consisted of an operations and support area. The support area contained twenty support buildings. By this time, the US intelligence community had measured the frequencies and azimuths of the transmitting antennas. They knew what was happening there in detail.

Three other dishes as big, or nearly as big as the one at Yevpatoriya had been built at other locations throughout the USSR, although the Soviet Union never developed the worldwide tracking network that the United States had constructed for both its civil and military space programs.

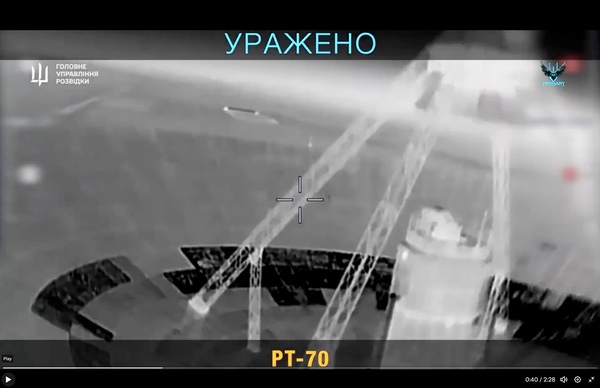

Drone view of the PT70 dish during a Ukrainian attack in summer 2025. Ukraine's military believes that this large dish is used to support the GLONASS navigation satellite system. (credit: Ukraine Ministry of Defense) |

Yevpatoriya today

According to space historian and analyst Bart Hendrickx, in recent years Russia began developing new optical space tracking facilities in multiple locations, including one in Yevpatoriya, which contained four optical telescopes. These are part of the Pritsel military space surveillance system, with the optical sites having the designation 3762. The tracking systems consist of optical telescopes located under domes and the observatory at the north facility is designated 3762/4.

In late August 2025, Ukraine launched drones at the 3762/4 observatory, aiming at one of two domes. It was unclear from the video if the drone damaged the observatory or merely impacted on the dome without exploding. At the same time of this attack, at least one drone was attacking the big RT-70 dish a few kilometers away. In video, the drone approaches the dish, which has some missing panels. Whether the drone hit the dish, and if it caused any damage, is unknown. It is also unknown if the dish was still in operation, although the missing panels imply that it was no longer used.

On September 10, 2025, Ukraine released another video of an attack on the 3762/4 observatory. Dramatically, a surface-to-air missile fired by the Russians failed to hit the drone before the drone impacted on the control building at the observatory and exploded. Another explosion is seen at another part of the facility.

Why Ukraine attacked Yevpatoriya is confusing. They apparently believe that the 3762/4 observatory and the big RT-70 dish are associated with the GLONASS navigation system. The extent of the damage, if any, is publicly unknown. However, the US intelligence community is certainly still watching Yevpatoriya.

Acknowledgements: Special thanks to Harry Stranger, Chris Pocock, Xin Lu, and Bart Hendrickx. Harry Stranger’s website is https://spacefromspace.com/.

Further reading:

“Military Targets on the Crimea Peninsula, USSR,” Central Intelligence Agency, Office of Research and Reports, September 30, 1957. CIA-RDP78T04753A000100160001-5

“Deep-Space Probe Tracking and Communication Center, Yevpatoriya, USSR,” National Photographic Interpretation Center, November 1963. CIA-RDP78B04560A001200010012-2

“Simferopol Space Flight Center, Deployed Comm/Elec/Radar Facilities, USSR,” National Photographic Interpretation Center,” June 1969. CIA-RDP78T04563A000100010029-1

“Yevpatoriya Deep-Space Tracking Center, USSR,” Photographic Intelligence Report, Central Intelligence Agency, August 1966. CIA-RDP78T05161A001000010049-5

“Yevpatoriya Deep Space Tracking Facility, North/Yevpatoriya Deep Space Tracking Facility, South,” National Photographic Interpretation Center, July 1969. CIA-RDP78T04563A000100010012-9

“Imagery Analysis Service Notes,” Central Intelligence Agency, Directorate of Intelligence, January 16, 1970. CIA-RDP78T04759A009700010047-0

“Activity at Selected Soviet Space Tracking Facilities, Deployed Commo/Elec/Radar Facilities, USSR” National Photographic Interpretation Center, March 1982. CIA-RDP82T00709R000100070001-9

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.