When second best is good enough: The Initial Defense Satellite Communications Systemby Dwayne A. Day

|

| The decision to proceed with the new system was also a major policy reversal. Whereas the Army had been responsible for the Advent satellite and the Air Force was responsible for the ground stations, now that was reversed. |

By 1962, Advent’s mass and costs had increased to such an extent that it was cancelled, with a lightweight version of the satellite was proposed instead. However, by December 1962, the lightweight geosynchronous satellite was still in limbo, with the Air Force making no moves to begin a formal procurement effort despite several companies already prepared to bid.[1] The Air Force was instead focused on a less-complex approach, known as the Initial Defense Communication Satellite Program, or IDCSP, later renamed the Initial Defense Satellite Communications System, or IDSCS. Recently, some never-before-published photos of the early IDSCS satellites have surfaced.

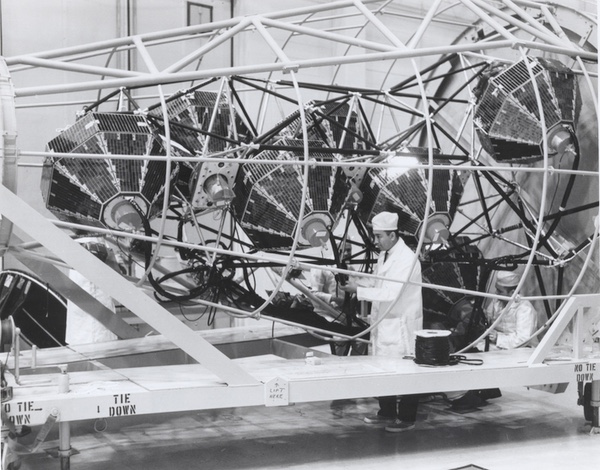

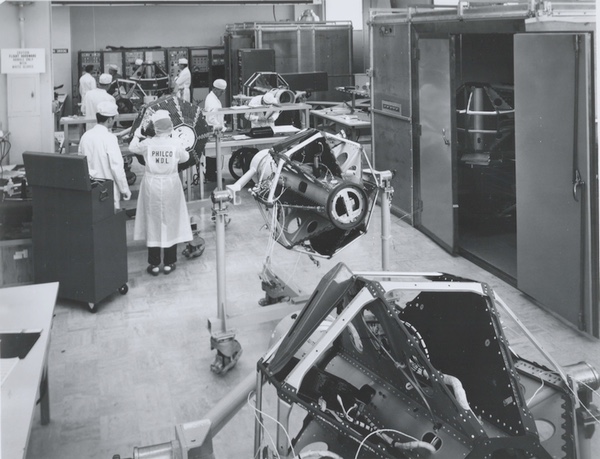

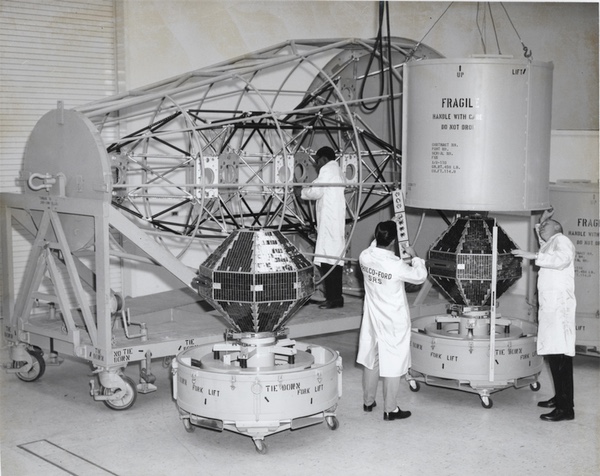

The relatively small satellites were tested on site. They were covered in photovoltaic cells. (credit: USAF) |

Program 369

In 1962, after Advent had been canceled, the Task X Committee, consisting of representatives of the Army, Navy, Air Force, ARPA, and the Rand and Aerospace Corporations, proposed placing multiple, relatively small satellites in medium-altitude orbits. By the end of 1962, Air Force Systems Command’s Space Systems Division began planning to brief potential contractors on this random-orbit, medium-altitude communication satellite program, now designated Program 369.[2]

The Air Force was interested in a medium orbit, 9,260-kilometer-altitude communication system which could involve as many as 20 satellites in random orbits at the same time. The satellites would move around the sky, requiring some movement of the ground antennas to keep track with them. As many as five to seven satellites could be launched by a single Atlas-Agena D rocket. Communications capability could be restricted to one to four channels in the initial program.[3]

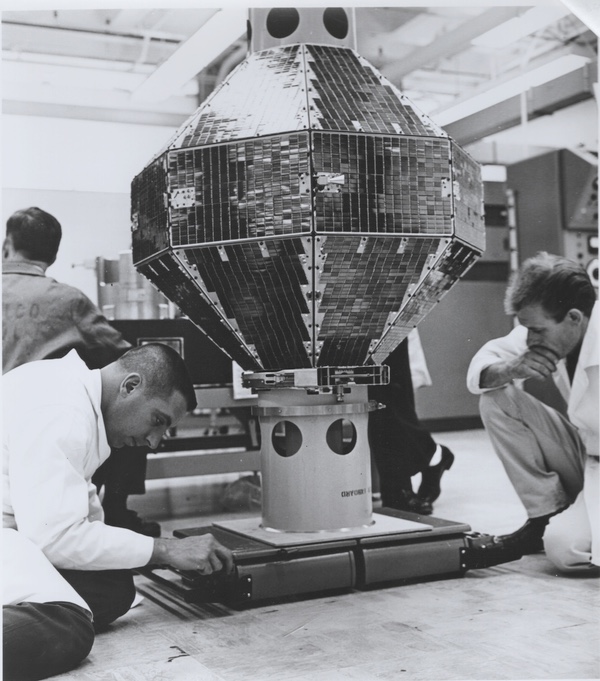

The satellites were manufactured by Philco, which was a major military computer provider at the time. (credit: USAF) |

The decision to proceed with the new system was also a major policy reversal. Whereas the Army had been responsible for the Advent satellite and the Air Force was responsible for the ground stations, now that was reversed, with the Air Force developing the satellites and the Army handling the ground terminals. The new satellites would require very little control.

After Philco won the competition to build the satellites, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara put the project on hold in October 1963 while the Pentagon negotiated over renting communications capability from the newly created Communications Satellite Corp. (Comsat). Negotiations dragged on until summer 1964 before they were suspended and the Air Force resumed work on the dedicated military communications program.[4] Although McNamara had hoped to buy satellite communications commercially, commercial providers could not meet many military requirements, particularly for secure communications. The Department of Defense would ultimately use commercial satellite communications, but for tasks that did not require high security.

In another cost-saving effort, in the latter half of 1964 the Pentagon tried to negotiate a “free ride” on experimental Titan III rocket launches rather than purchasing dedicated Titan III rockets after the vehicle was declared operational. The House of Representatives criticized the effort later that year as a “plan for short-range economics depending on a high-risk program that may prove costly in the end.”[5]

The original plan for the medium-altitude satellite program had an estimated cost of $60 million for the satellites and a total of $165 million, including ten Atlas-Agena launches. A modified approach, using a much higher orbit and fewer launches, cost $33 million. This was far cheaper than Advent, which had grown from the original $140 million estimate to $325 million (see “Aiming too high: the Advent military communications satellite,” The Space Review, September 26, 2022.)

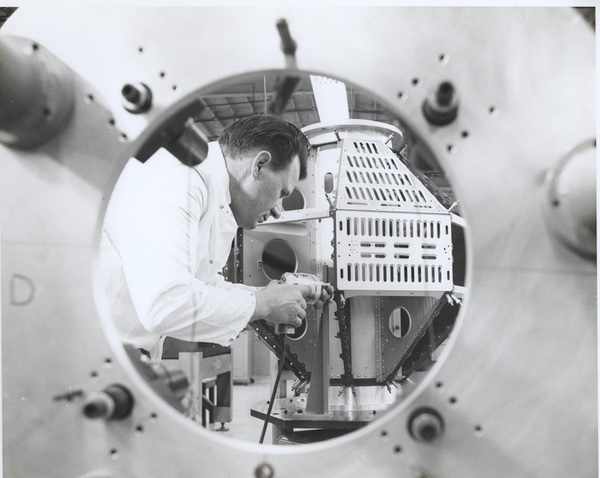

While the Pentagon negotiated—ultimately unsuccessfully—with Comsat, Program 369 proceeded in a design phase. Initially, the satellites were intended to launch on Atlas-Agenas. But the possibility of using the new Titan IIIC was attractive, and so for a time, the satellites were designed to be able to launch on either vehicle, to equatorial or polar orbits. The reasoning was that if the Titan IIIC was ultimately selected, the Atlas-Agena would provide “insurance” until the Titan IIIC had fully proven itself.

The satellite dispenser was initially designed to be carried atop either a Titan IIIC or Atlas-Agena D.(credit: USAF) |

According to a contemporary history of the program, “this convertibility had three aspects – first, the satellite and dispenser had to be mechanically, thermally and electrically suitable for use with either vehicle from launch through ascent, parking orbit, transfer orbit and final injection. Second, the spacecraft had to be designed dynamically, magnetically and electronically for medium or high altitude. Finally, the thermal, solar cell and repeater design had to be acceptable in polar or equatorial orbits.”[6]

| Philco established a production line capable of building one satellite every four days. This was possible in large part because the satellites were relatively simple. |

This decision to design for either Atlas or Titan ultimately had a cost. “There were many conflicts that were resolved only by compromising the performance in both cases, but the program flexibility and non-dependence on a new booster design justified them,” engineers involved in the program explained. “The convertibility feature was maintained through the early part of 1965. At that time, some of the conflicts became serious, the compromises more painful, and most important of all, the Titan III program was looking good.” Rather than the medium-altitude orbits, the Air Force could use the Titan IIIC to place them into near-synchronous orbits.[7]

The first Titan IIIC had launched successfully in June 1965. A second launch, in October, had failed. A third launch, in December, had been partially successful. The Air Force decided to eliminate the Atlas-Agena option and launch the satellites atop the fourth Titan IIIC launch.

The IDSCS satellites used the new Titan IIIC rocket, which placed them in a near-synchronous orbit. Concern about the availability of the Titan IIIC was a major uncertainty early in the program. (credit: Peter Hunter Collection) |

Simple satellites

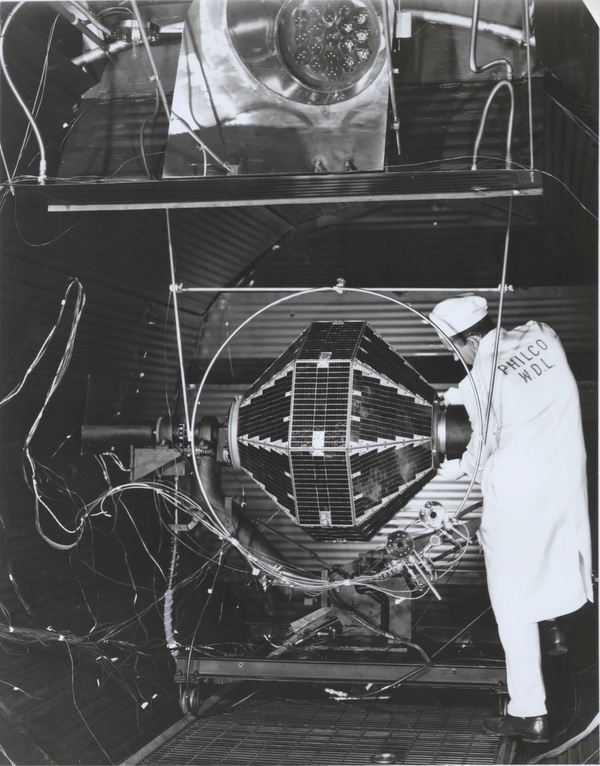

Philco had previously built the Courier IB satellite and had built computers for the military. The company established a production line capable of building one satellite every four days. This was possible in large part because the satellites were relatively simple. They had no moving parts, no batteries for electrical power, and limited telemetry capability to report the status of the spacecraft. The satellites could not be commanded from the ground, which had the benefit of making them resistant to Soviet tampering. They could provide two-way circuit capability for 11 “tactical-quality” voice circuits, or five “commercial-quality” circuits. The latter could transmit digital or teletype data.

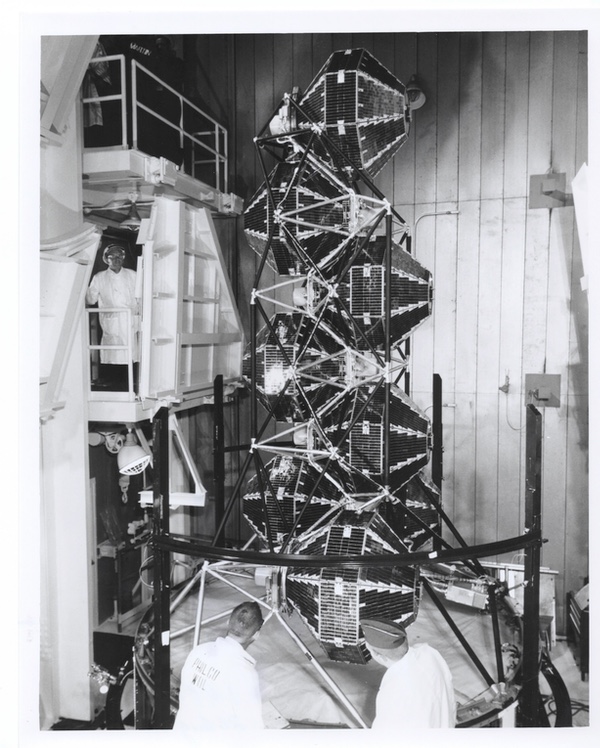

Philco was capable of manufacturing a satellite in approximately four days. Each launch carried eight satellites. (credit: USAF) |

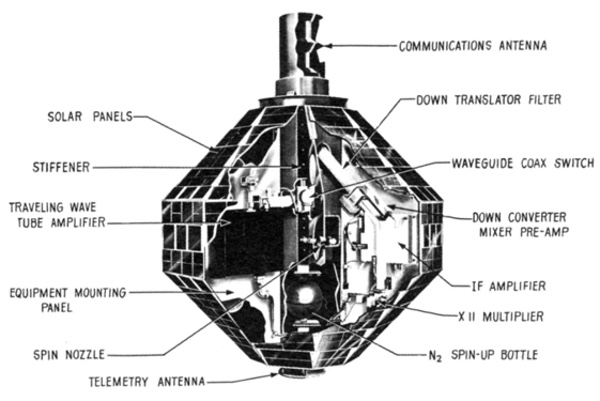

Each satellite was a polyhedron with twenty-four faces, weighed 45 kilograms, was a meter in diameter and a meter high, and was covered with 8,000 solar cells. The communications equipment consisted of a single-channel 8,000-megahertz receiver, and a 20-megahertz double-conversion repeater. In addition, they would have a three-watt traveling-wave-tube amplifier transmitting around 7,000 megahertz. The satellites had three-year operational lifetimes. In service, they often lasted twice as long.[8]

The IDSCS satellites were about a meter wide and a meter tall, weighed 45 kilograms, and relatively simple. (credit: USAF) |

In June 1966, the Air Force launched seven communications satellites into near-synchronous orbits of 33,877 by 33,655 kilometers (an eighth satellite was a technology demonstrator). A second cluster of eight satellites was launched in August, but failed to reach orbit. Two more launches, in January and July 1967, increased the number of satellites in orbit.

The relatively small satellites were tested on site. They were covered in photovoltaic cells. (credit: USAF) |

According to those who worked on the program, the orbit options had been extensively studied. The near-synchronous orbit was selected in case a satellite in the cluster failed. If they were placed in geosynchronous orbit, that failed satellite would remain in place for a long time. But in near-synchronous orbit, the cluster would slowly drift. “Because of this slow drift, satellites will stay in view of the ground stations for several days but a malfunctioning or failed satellite will not completely destroy the communications capabilities of a particular link.”[9]

The system was declared operational before the launch of the last group of eight satellites and renamed the Initial Defense Satellite Communications System (IDSCS). The final launch of eight satellites in June 1968 atop a Titan IIIC brought the total number in orbit to 35 satellites.[10] It was years later than planned, but the Air Force finally had its communications satellite system.

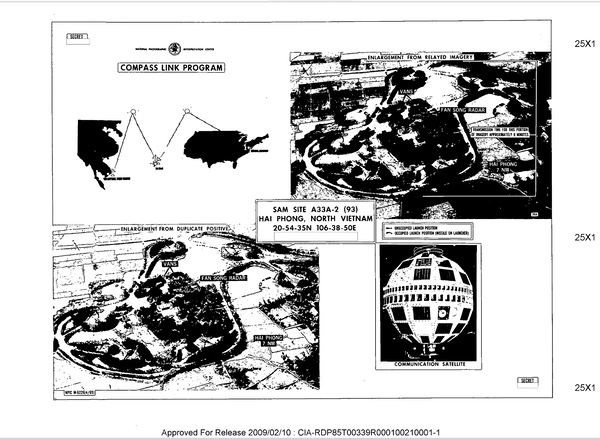

Compass Link was a system for scanning photographs in Vietnam and transmitting them via satellite to Washington, DC, where they were analyzed at the National Photographic Interpretation Center. The scanning hardware had been developed for the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program. Although little is known about Compass Link, it did use IDSCS satellites. (credit: CIA) |

Vietnam goes to orbit

In 1964, the US Army established a ground station in Saigon to relay messages via NASA’s Syncom satellite. In July 1967, the military installed satellite ground terminals at Saigon and Nha Trang for communicating via the IDSCS satellites. They linked military forces in Vietnam directly to Washington, DC. This provided new capabilities compared to existing telecommunications networks.

| Communications satellite technology was advancing rapidly throughout the 1960s, pushed in part by clear commercial demand as well as significant military investment. |

One of the more unusual and secretive uses of this new capability was Project Compass Link, which provided circuits using the IDSCS satellites to transmit high-resolution photography between Saigon and Washington, DC. This meant that photos taken by tactical aircraft over the battlefield could be analyzed in Washington. After the planes returned to base, their photos were developed and taken to the transmission center. The ground stations had a scanner that could scan a photograph for transmission. This scanner had been developed using technology originally intended for the Manned Orbiting Laboratory program (see “Live, from orbit: the Manned Orbiting Laboratory’s top-secret film-readout system,” The Space Review, September 18, 2023.) To date, information on the Compass Link equipment and how it was used remains scarce.

Other commercial communications satellite systems were also used by US military forces in the Pacific during this time. The commercial systems were used for administrative and logistical requirements, and the military systems were used for more sensitive communications.

Satellites undergoing fit checks prior to shipment to the launch site. (credit: USAF) |

Evolving communications

IDSCS was intended to be an interim system until a better and more capable communications system was developed. The Air Force was aware of the system’s limitations from the start, and planned for a follow-on program to address many of them, increasing lifetime, adding better encryption and anti-jamming capability, as well as operating in geosynchronous orbit, the goal originally established with Advent in the late 1950s. Communications satellite technology was advancing rapidly throughout the 1960s, pushed in part by clear commercial demand as well as significant military investment. The Air Force sponsored experimental communications satellites like Tacsat and the LES satellites, and NASA also sponsored communications satellites to develop new technologies. Although commercial industry sought to satisfy growing demand, the government had unique needs and could not rely on the commercial market to satisfy them.

In 1971, the Air Force launched the first of the Defense Satellite Communications System II (DSCS II) satellites. DSCS II was a much larger, spin-stabilized satellite placed in geosynchronous orbit, but did not have all the features that the Air Force desired; they would later be included in the DSCS III satellites. Once DSCS II satellites became operational, the Air Force primarily relied upon large satellites in geosynchronous orbit for its primary communications requirements, a situation that is only beginning to change today with the advent of large numbers of small comsats in low Earth orbit.

Acknowledgement: the author wishes to thank Jamie Draper and Jim Behling for assistance in obtaining the photographs used in this article, and Aaron Bateman for providing the AIAA history overview.

References

- “Defense is Pushing Random-Orbit Satellite,” Aviation Week and Space Technology, December 24, 1962, p. 23.

- Philip J. Klass, “DOD Communication Satellite Launch Set,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, May 9, 1966, p. 33.

- “Military Comsat Bidder’s Briefing Set,” Aviation Week and Space Technology, February 4, 1963, p. 31.

- H.B. Kucheman, Jr., W.L. Pritchard, and V.W. Wall, “The Initial Defense Communication Satellite Program,” AIAA Paper No. 66-267, AIAA Communications Satellite Systems Conference, May 2-4, 1966.

- Philip J. Klass, “Military Comsats Deploy for Global Cover,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, June 27, 1966, pp. 25-26.

- “The Initial Defense Communication Satellite Program,” p. 4.

- Ibid.

- David N. Spires and Rick W. Sturdevant, “From Advent to Milstar: The U.S. Air Force and the Challenges of Military Satellite Communications,” in Beyond the Ionosphere: Fifty Years of Satellite Communication, Andrew Butrica, ed. NASA SP-4217, 1997, pp. 67-69.

- “The Initial Defense Communication Satellite Program,” p. 5.

- Ibid.

Note: we are now moderating comments. There will be a delay in posting comments and no guarantee that all submitted comments will be posted.