Take off and nuke the site from orbit (it’s the only way to be sure…)by Dwayne A. Day

|

| Ever since the dawn of the space age lunar base proponents have had a difficult time explaining exactly why a lunar base is needed and what it can do that justifies its immense cost. |

Richardson’s article focused primarily on the physics of the Moon: the low gravity, the lack of air, the trajectory and velocity calculations for firing rockets at the Earth. Rather than advocate that the United States should build a lunar rocket base, Richardson warned that another country could undertake a secret project to develop a lunar base and achieve strategic surprise against the United States. He did not clearly explain why the Moon would be a good place for basing missiles other than presumed safety from Earth observation, and noted that it would take at least a day for a rocket to reach Earth with its warhead. Considering that there were other means of basing long-range strategic weapons that did not involve the massive cost of a space program and a lunar base, Richardson’s idea was fanciful at best. But Collier’s was a large circulation magazine, not a science fiction pulp, and this short article certainly reached a big audience.

Richardson was not the only person writing about the possibilities of using space as a platform for attacking Earth. Robert Heinlein co-wrote a non-fiction article in August 1947, also for Collier’s, called “Flight into the Future.” Heinlein and his co-author, US Navy Captain Caleb Laning, suggested basing atomic weapons in orbit, and Heinlein later used this idea in his book Space Cadet. The 1950 movie Destination Moon, which Heinlein co-wrote, also echoed a similar theme (see “Heinlein’s ghost (part 1)”, The Space Review, April 9, 2007). One of the characters in the movie explains why a lunar base is necessary: “There is absolutely no way to stop an attack from outer space. The first country that can use the Moon for the launching of missiles will control the Earth. That, gentlemen, is the most important military fact of this century.” (Decades later, Allen Steele would explore the idea of a missile base on the Moon in his novel The Tranquility Alternative.)

In December 1956, the commander of Air Research and Development Command, Lieutenant General Thomas S. Power, established a Guided Missile and Space Vehicle Working Group. Three months after Sputnik, in December 1957, that group issued a “Special Report Concerning Space Technology” that laid out an “ARDC Five Year Projected Astronautics Program” including a “Manned Lunar-Based Intelligence System,” with a projected first flight in 1967. By January 1958 the Air Force initiated Program 499, a “Lunar Base System” and by March the Air Force was formalizing plans for a “Manned Lunar Base Study.”

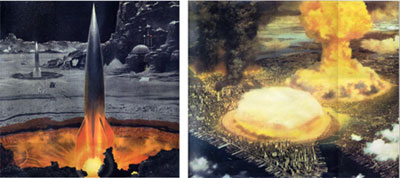

It did not take the Air Force leaders long to start talking about their plans in public. In January 1958 USAF Brigadier General Homer A. Boushey spoke in front of the Aero Club of Washington, DC. Boushey’s speech was reported in U.S. News & World Report under the title “Who Controls the Moon Controls the Earth.” Boushey justified the Moon base in terms of national security using language that could have been taken straight from Heinlein’s Destination Moon eight years before: “The Moon provides a retaliation base of unequaled advantage,” Boushey said. “If we had a base on the Moon, the Soviets must launch an overwhelming nuclear attack toward the Moon from Russia two to two-and-one-half days prior to attacking the continental U.S. first, only and inevitably to receive, from the Moon—some 48 hours later—sure and massive destruction.”

Boushey was not the only Air Force officer publicly calling for a Moon base to provide retaliatory capability. In early March 1958, Air Force Lieutenant General Donald L. Putt spoke before the House Armed Services Committee about various possible responses to the Soviet Sputnik launch, including a base on the Moon. According to a Time magazine report, “Since the Moon’s gravitation is only one-sixth as strong as the Earth’s, it should be easier to shoot at the Earth from the Moon than in the other direction. The Moon’s lack of atmosphere might make it possible to catapult Earth-bound missiles out of deep shafts. Both the Moon base and its weapon launchers could be on the far side of the Moon, forever invisible from the Earth, but all of the turning Earth could be examined from the Moon with telescopes.” Putt also made a suggestion that seems amazing when looking back on fifty years of space history: “We should not regard control of the Moon as the ultimate means of ensuring peace among the Earth nations,” Putt said. “It is only a first step toward stations on planets far more distant… from which control over the Moon might then be exercised. Nevertheless, the Moon appears to be of such significance that we should not let another nation establish a military capability there ahead of us.”

And so in the fall of 1958 the advanced systems studies office of the Air Force Ballistic Missiles Division in Los Angeles commissioned several studies by defense contractors to evaluate the strategic value of manned spaceflight. These were “Systems Requirement” studies. SR-181 was called the Strategic Earth System Study (or alternatively, the Global Surveillance System), SR-182 the Strategic Interplanetary Study, and SR-183 the Lunar Observatory Study. All three of the studies apparently included a nuclear weapons component. SR-183 eventually gave birth to SR-192, a Lunar Strategic System study. That’s not where it ended, either. A declassified 1963 report lists several other studies as well: SR-17527, the Military Test Space Station; SR-17532, the Permanent Satellite Base and Logistic Study; SR-79503, the Strategic Orbital System, SR-79814, the Space Logistics, Maintenance and Rescue System; SR-79821, the Earth Satellite Weapon System; and SR-79822, the Advanced Earth Satellite Weapon System. Clearly the Air Force had a lot of people looking at various projects for putting humans in space for “strategic” purposes, as well as orbiting nuclear weapons. Dr. Strangelove would have been orgasmic.

| Gen. Putt made a suggestion that seems amazing when looking back on fifty years of space history: “We should not regard control of the Moon as the ultimate means of ensuring peace among the Earth nations,” Putt said. “It is only a first step toward stations on planets far more distant… from which control over the Moon might then be exercised.” |

Unfortunately for historians, none of these studies has been found and released, nor has anyone discovered significant supporting documentation like memos, letters, and other paperwork associated with the studies—all of these references (the ones in quotes above), with the exception of the magazine articles quoting Generals Boushey and Putt, tend to be footnotes or citations in other reports. Researching the history of early Air Force lunar base studies is like reading Wikipedia: every article refers to some other article that refers to another article that, at best, refers to a list of documents or studies, not the actual documents or studies themselves.

The Lunar Observatory Study summary report was declassified in the 1970s, but is only nine pages long and lacks many details. These reports may still exist somewhere, buried in dusty government archives next to the Ark of the Covenant or even in the garage of some retired Air Force officer who once illegally took a copy home. For the most part historians simply know that they existed, but almost nothing about what they addressed. The most likely explanation for their demise is that they were the victim of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who took over the Pentagon in 1961. McNamara’s whiz kids applied systems analysis and economic models to weapons systems and many of the Air Force’s pie-in-the-sky ideas were soon canceled for the simple reason that they were incredibly expensive ways of doing things that really did not require doing. Although McNamara has a legacy overshadowed by Vietnam, in the early 1960s he managed to kill a number of dubious and expensive Air Force programs, and it seems probable that the military lunar base was one of them.

But it is also apparent that there was no discussion of lunar missile bases in the highly active deterrence theory community at the time these Air Force studies were underway. By the late 1950s the RAND Corporation was producing voluminous studies on deterrence theory, including the need for survivable nuclear forces capable of riding out a first strike and smashing the commies into dust. Some of RAND’s most famous thinkers—the “wizards of Armageddon” to use Fred Kaplan’s immortal phrase, men like Bernard Brodie, Herman Kahn, Henry Kissinger, and Albert Wohlstetter—were writing publicly about deterrence theory. Lunar bases equipped with nuclear weapons do not appear in any of this literature. The late, great Brodie’s seminal book Strategy in the Missile Age, first published in 1959, makes no mention of the Moon as a missile base. Thus, it appears that the Air Force’s strategic space studies had no discernible impact on Cold War nuclear deterrence and are little more than a footnote in Cold War history.

However, their impact on the American space program—and thus, space history—may be greater than historians have recognized. The fact that these Air Force SR studies have not been found has apparently distorted the historical record of early American lunar planning. A similar Army study, known as Project Horizon and conducted at the same time, has been declassified in its entirety for many years, and attracted much more attention from historians. But the Air Force studies involved many more companies and personnel and lasted over a longer period of time, and it is possible that they have had a subtle legacy that has been overlooked by space historians.

A lonely ambassador and keen observer

Fortunately for historians, there is some new information on the Air Force’s SR-183 study effort in the form of detailed notes taken by NASA official Edwin P. Hartman who attended a mid-point briefing on the lunar study. Hartman’s records are preserved in the National Archives regional office for southern California at Laguna Niguel, south of Los Angeles. They provide much more detail and insight into the Air Force lunar study than has been previously disclosed.

Starting in the early 1950s, Hartman was the head of the Western Support Office of the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics (NACA), which was absorbed into NASA when it was created in fall 1958. Hartman’s job was to serve as the representative of NACA and then NASA in southern California. NACA conducted aeronautics research and did not buy much hardware, and so Hartman was in many ways a lonely ambassador representing NACA’s interests in southern California, as well as the organization’s eyes and ears on the West Coast. As NASA increased in size and began to sign hardware development contracts with aerospace companies in California, the agency increased its presence on the West Coast and Hartman’s role changed. By the early 1960s the agency needed representatives at the factories that were building the Apollo spacecraft and the Saturn rockets. But during the 1950s Hartman was pretty much the sole agency representative, traveling to various aerospace companies and obtaining briefings on their work and then reporting back to his bosses in Washington, such as NACA director Hugh Dryden.

Hartman was a keen and meticulous observer and his reports from this era are a treasure trove for many reasons, including the fact that so many corporate records have never been preserved. Hartman reported not only on what projects the companies were undertaking, but also their key figures and personalities and even the companies’ financial situations and organizational and other problems. Although his memos represent his personal point of view, and sometimes humorously demonstrate the difficulties for an airplane expert to adapt to the new subject of spaceflight (for instance, referring to “turns” around the Earth instead of “orbits”), in some cases history has revealed that Hartman’s observations were extremely astute.

Charity work with taxpayer money

In late March 1959 Hartman attended several briefings at the Ballistic Missile Division in Los Angeles conducted by industry teams on the results of their studies concerning SR-183, the lunar systems or lunar observatory study. According to Hartman, there were four industry teams, consisting of North American Aviation’s Missile Development Division and RCA; Boeing, Westinghouse, and Aerojet Nucleonics; Republic Aviation and Systems Corp. of America; and United Aircraft Corp. and Minneapolis-Honeywell. The Douglas Missiles Division participated on its own. Somewhat surprisingly, Lockheed, which then had the most active space program, the WS-117L reconnaissance satellite program funded by the Air Force, was not a participant. According to a 1992 history paper by Lockheed employee R.D. Allen, the company did bid on the studies, but was apparently not selected. By late 1958 Ballistic Missile Division officers were concerned that Lockheed was overextended and so they may have banned the company from participating in the study effort.

| The Air Force studies involved many more companies and personnel and lasted over a longer period of time, and it is possible that they have had a subtle legacy that has been overlooked by space historians. |

The briefings occurred over several days and Hartman missed the final briefing by United Aircraft and Minneapolis-Honeywell and therefore did not report on their work. These companies were presenting their results at the mid-point of the one-year study. After these briefings, information on the study leaked (or was officially given) to Aviation Week magazine, as happened again in September 1959 when the study was concluded. But Aviation Week lacked the detail that Hartman provided about the Air Force effort in his extensive notes. The Army study was apparently initiated in March 1959, only shortly before the Aviation Week article appeared, but the decision to finish the Project Horizon study before the rival Air Force finished its study was undoubtedly due to a desire to beat the Air Force to the punch.

There is conflicting information about whether the studies were funded by the Air Force or undertaken using company money. According to the final summary report produced a year later, three of the individual companies were funded whereas the others were “voluntary.” In his notes Hartman implied that all of the teams used their own money for what must have been expensive studies involving a lot of people. “The companies that undertake SR studies for the Air Force do so largely at their own expense,” he explained. But Hartman also had a rather blunt insight into what a “voluntary study” really meant: “As the income of most aircraft companies comes mainly from the government, it is obvious that the studies are paid for by the government with the cost appearing as overhead charges on military contracts,” he wrote. The fact that at least part of the work was not directly paid for by the government may explain why these SR studies have so far eluded historians—very little paper in the form of final reports may have actually made its way into the hands of government officials, and what did was probably stamped as industry proprietary.

“The objective of SR-183,” Hartman wrote, “is to determine a sound and economical approach for the establishment of a manned intelligence observatory on the Moon. The Moon is considered a favorite vantage point from which to observe enemy actions in space. Also, because of its low gravity, the Moon is believed (by some people) to be a good platform for launching defensive vehicles.”

Based upon Hartman’s description of the four industry briefings he attended, it is clear that these studies clearly started with each team suggesting multiple ideas about what the Air Force could do on the Moon, determining the technical aspects of them, and trying to flesh out the basics of how to start a lunar base project. Given the fact that the teams had only six months and virtually no experience at all in spaceflight—certainly not human spaceflight—it is not surprising that they often proposed some rather unrealistic, even fanciful ideas. Some of their ideas are still around even today, and may be no more possible now than they were half a century ago.

But a funny thing also happened on the way to the Moon: the thought experiment of a Moon base highlighted the superiority of other ways to do things in space. The contractors concluded that a number of missions really could be better accomplished from different locations, like geosynchronous orbit. Much like today, it appears as if government officials picked the location and then asked contractors to figure out what, if anything, they could do there, rather than figuring out what they wanted to do, and then deciding the best location for doing it.