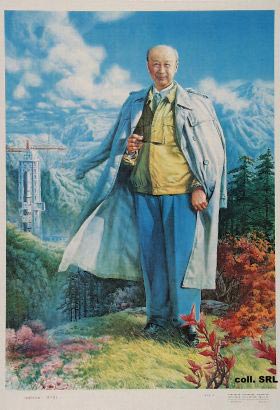

A dragon in winterby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Tsien is admittedly a difficult subject, full of contradictions and mystery. But the problem has not been with the subject, but the people writing about him—with a notable exception. |

Tsien was born in 1911 in China and in the 1930s came to the United States on a college scholarship. He was brilliant, learned quickly, and soon acquired a Ph.D. His area of expertise was aeronautical theory and he became a protégé of the famed Theodore von Kármán at Caltech (it is worth noting that, Tsien, von Kármán, and so many other brilliant American scientists came from somewhere else). During World War 2 Tsien conducted rocketry research and as the war wound down he was involved in the effort that sent American scientists to war-torn Germany under military sponsorship to investigate German technology. He was given the temporary rank of colonel in the Army and was often right on the front lines in order to access information and people as soon as they became available, and before the Russians could get to them. Tsien was one of the first people to interview Wernher von Braun after he was captured.

American historian Iris Chang published the definitive biography of Tsien in 1995 titled Thread of the Silkworm. Chang recounted how in summer 1950 the FBI suddenly showed up at Tsien’s door and accused him of being a communist based upon his friendship with several other alleged communists and his attendance at social gatherings of leftists. These friendships and gatherings occurred in the late 1930s, when Tsien was still a shy, quiet graduate student, and before he became involved in military work and rose to fame and honor. The FBI also revoked Tsien’s security clearance.

The reason that Tsien suddenly became a focus for suspicion appears to be a case of a misunderstanding spiraling out of control. Tsien made a request to travel to Communist China to visit his elderly parents (whom he had previously visited in 1947 with US government approval). This made a government official uneasy, prompting him to suggest that Tsien’s request be denied. While this was being considered, the FBI discovered a list of people who had attended a social gathering that they suspected was a meeting of “Professional Unit 122 of the Pasadena Communist Party.” It was a time where Senator Joseph McCarthy and others were claiming that any association with communists was essentially the equivalent of being a communist.

By all accounts Tsien was stunned by the allegations and vigorously denied them. He had never demonstrated any real interest in politics at all. By this time he was highly regarded, especially on the Caltech campus, and his shyness had long faded, replaced by arrogance. The allegations apparently shook him to his core, so much so that he suddenly announced plans to depart for China permanently two weeks later. This decision, and the fact that Tsien started to pack up his substantial—unclassified—technical library, only heightened FBI suspicions. The government essentially placed him under house arrest, without ever charging him.

All of Tsien’s colleagues, including his famous mentor von Kármán, rallied to his defense. Some even traveled to Washington to speak on his behalf, and Caltech hired a lawyer to defend him. Tsien reversed his plans to leave for China and decided to stay and clear his name. But the FBI kept Tsien under virtual house arrest for five years before he was deported in 1955. The government justified the long detention by claiming that after five years he would no longer know any valuable secrets. What they failed to recognize was that the man himself was far more important than the information he knew. The man who had only wanted to travel to China to visit his parents was now forced out of the United States, sent to China with a shove and a kick.

Iris Chang’s account of Tsien’s life is highly readable and meticulously researched. She noted that the Immigration and Naturalization Service file on Tsien contained no evidence that he was a communist or a spy. Although she had portions of Tsien’s FBI file as well as a large Army intelligence file on him, Tsien’s full FBI file had not been released in time for her book. Neither did she have any access to Tsien himself. Like a careful historian, she acknowledged that without his complete FBI file, it was impossible to make a more firm conclusion about his actions leading up to his decision to leave the United States. Nevertheless, the US government never proved that Tsien was a communist, nor a spy, and there is substantial evidence that what had started out as a bureaucratic impulse to prevent him from leaving had escalated into unproven charges and Tsien’s ultimate deportation.

| The man who had only wanted to travel to China to visit his parents was now forced out of the United States, sent to China with a shove and a kick. |

After he was deported to China, Tsien was quickly enlisted by the communist government there to aid its nonexistent ballistic missile program. But before Tsien could even start a program, he had to teach students about the basics of aeronautical engineering. He then helped to develop Chinese ballistic missiles during the 1960s and probably later, although Chang has acknowledged that this period of Tsien’s life is still murky. What is clear is that over time, perhaps out of bitterness at the way he was treated by the country that had educated him and then held him a virtual prisoner in his own home before kicking him out, Tsien became a committed communist. In fact, the formerly apolitical Tsien did not merely adopt communism, but embraced it wholeheartedly, becoming a parody of the apparatchik who in the end comes to love Big Brother. By the 1980s and 1990s his former students and even his closest friends were scared of him because of his loyalty to the Communist Party. Tsien also became interested in pseudo-science, including UFOs and extra-sensory perception. The aeronautical theorist had crossed over to political and scientific mysticism.

Thread of the Silkworm was the first of Chang’s three books. Her next book, The Rape of Nanking, published in 1997, made her famous, especially among Chinese Americans, because it recounted in excruciating detail the brutal Japanese occupation of that Chinese city. She followed this in 2003 with The Chinese in America: A Narrative History.

When she wrote Thread of the Silkworm Chang stated that the biggest gaps in knowledge about Tsien concerned his involvement in China’s missile and space programs. She speculated that those gaps would start to close over time, as more of Tsien’s contemporaries wrote their memoirs. She expected that Tsien’s closest colleague would write Tsien’s biography after the elderly Tsien died. And Chang said that she might someday revisit the subject of Tsien’s life.

Unfortunately, that will never happen. Chang’s energy, meticulous research, and devotion to historical honesty all came with a price: she suffered from bipolar disorder. She finally lost a long struggle with depression and in 2004 at the age of 36 she shot herself with an antique pistol. Her death shocked many Chinese Americans, some of whom speculated that she had been killed by nationalist Japanese in retaliation for her book about Nanking. It seemed impossible that a beautiful woman of such extraordinary talents would simply kill herself, especially by using a firearm. But in a new book, Finding Iris Chang: Friendship, Ambition, and the Loss of an Extraordinary Mind, Chang’s friend, Paula Kamen, describes Chang’s life and descent into the depression that took her life. To the friends who knew her, there were many signs that Chang was disturbed, and signals that all was not right with her life. For instance, she had used a surrogate mother in order to have a child, but hid inside her house for months, until after the baby was born, and then claimed that she had given birth, deceiving even her closest friends.

With the sad death of Iris Chang, it will fall to some other researcher to pick up the story of Tsien’s life, but it is unlikely that that person will possess Chang’s gifts. And it is much more likely that Tsien’s history will be told by people who have limited research skills, but try to compensate for it with ideology, repeating some of the same sloppy errors that ultimately resulted in a brilliant mind being deported to one of America’s Cold War enemies.

|

The most recent example of this can be found in an article published on a think tank website that went unnoticed until its author followed it with a more public article that gained the attention of the space community. A few weeks ago, Richard Fisher, Jr. published an op-ed article in The Wall Street Journal Asia edition advocating that the United States keep the Space Shuttle in operation beyond 2010 to serve as a “deterrent” to China’s own alleged spaceplane ambitions. That was only one of several dubious assertions in Fisher’s op-ed (another being the ridiculous claim that China has long sought to “dominate” space, something that not even the most strident anti-China hardliners claim; China is primarily interested in denying America’s ability to dominate space). Fisher’s op-ed was largely based on his earlier, little noticed December 17 analysis piece about an alleged Chinese spaceplane that was published on the website of the International Assessment and Strategy Center.

According to the think tank’s website bio, Fisher was one of the authors of a 1999 congressional document that has done significant harm to American space policy. In his December article, Fisher demonstrates a remarkably shallow grasp of current space policy issues. For instance, he never bothers to cite any of several books on the Chinese space program. But he briefly mentions Tsien, and quotes one of the 1999 report’s more preposterous comments about him.

| Over time, perhaps out of bitterness at the way he was treated by the country that had educated him and then held him a virtual prisoner in his own home before kicking him out, Tsien became a committed communist. |

In 1998, following allegations that nuclear weapons secrets and rocket technology had been illegally transferred to China, the House of Representatives conducted an investigation. The investigation was named after its chairman, Republican Christopher Cox of California. Cox left Congress in 2005 and is currently the chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission, where at least he no longer has input into American space policy. Officially, the Cox Report was known as the report on U.S. National Security and Military/Commercial Concerns With the People’s Republic of China. It remains one of the more infamous space policy documents of the past two decades, having a profound effect on American space policy, among other things resulting in severe restrictions on the export of American space-related technology.

The report was a sloppy piece of work, full of extraordinary leaps of logic, dubious allegations, and incorrect facts. As one example, the report incorrectly stated the payload capabilities of the Space Shuttle, leading some people to question why, if an American congressional report could not even get details of American spacecraft correct, the report could be trusted in its conclusions about Chinese rockets and spacecraft?

The larger policy conclusions and factual flaws of the Cox Report have been discussed elsewhere, although they certainly remain worth of further discussion. But the report did also briefly discuss Tsien. Tsien was not a mere footnote to the report, but an anchor. The report’s authors wanted to demonstrate a long history of China both acquiring knowledge of rocketry from other countries, and using espionage to do so. By discussing Tsien, they could supposedly prove that the events of the 1990s that they were so concerned with had been put in motion in the 1950s.

Chapter 4 of the report, on China’s missile and space forces, includes this opening teaser: “The early development of the PLA’s indigenous ballistic missile programs was marked by Soviet assistance, and by the guidance of a Chinese citizen who had returned to the PRC after working on the U.S. Titan intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) program.” The report further stated that Tsien Hsue-shen was “a Chinese citizen who was trained in the United States and had worked on classified U.S. missile programs, including the Titan intercontinental ballistic missile program.”

The report frequently cited Iris Chang’s biography of Tsien. The report stated: “During the 1950s, allegations arose that Tsien was spying for the PRC. He lost his security clearances and was removed from work on U.S. ballistic missiles.” Then came the money quote: “The allegations that he was spying for the PRC are presumed to be true.”

That is the quote that Richard Fisher re-used in his December article on the Chinese spaceplane: “The allegations that he was spying for the PRC are presumed to be true.”

But presumed to be true by whom? And where is the evidence?

The report also stated, “There were additional allegations that Tsien attempted to ship classified documents to the PRC before he left in 1955.” For this fact, the report cited Chang’s book, which does indeed say that there were “allegations” that he did this, and also states that those allegations were false. What Tsien sought to ship back to China was his unclassified personal library.

To demonstrate just how factually sloppy the Cox Report was, simply consider the first statement about Tsien’s work on the Titan ICBM, which the report repeats six times in chapter 4.

In reality, work on what became the Titan 1 ICBM was authorized in April 1955, the Air Force solicited bids in May, a contract was awarded to the Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Company in October, and the first production Titan was delivered to the Air Force in June 1958, with a flight test shortly thereafter. The first flight of a Titan 2 (a missile shown in a photo in the Cox Report) was in December 1961.

Tsien was deported in September 1955.

Unless Tsien possessed the secret of time travel, there is no way that he could have worked on the Titan ICBM before the program even started. But the Cox Report’s authors—including Fisher—did not bother themselves with unimportant issues like facts and causality. They were on a mission to prove espionage and the theft of American missile secrets, in 1998 and in 1955, and were not going to let mere logic stand in their way.

Concerning the allegation that Tsien had worked on the Titan ICBM, and the allegation that he had been a communist spy while he was in the United States, the report cited a “Department of Defense briefing to Select Committee, December 11, 1998.”

| Unless Tsien possessed the secret of time travel, there is no way that he could have worked on the Titan ICBM before the program even started. |

I somehow doubted that the DoD had actually informed the committee either of these things, suspecting that they were probably the result of sloppy staff work by the report’s authors. So I sought information on the briefing. I concluded that any such briefing on Tsien’s espionage would probably have been made by the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), and I submitted a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to DIA for any briefing that they made to the committee. After several months I received a response from DIA that they could find no such records. It is possible that the DIA has such records and they simply did not turn up during a search for my FOIA request. It is equally possible that no paper records ever existed, or that they exist in some other DoD agency. But whoever wrote that section of the report could easily have learned the facts from public sources. After all, they had a copy of Iris Chang’s book, and they could have looked up the date of the start of the Titan missile program and seen that there was no way he could have worked on a program that had not even started before he was deported to China. So it seems likely that the same people who “presumed” that the espionage allegations against Tsien were true are the same ones who presumed that he could have worked on the Titan—i.e., idiots.

Soon after the Cox Report’s release, numerous people reported on these and other problems. Iris Chang herself declared that the report had misused her research: “As the person who wrote the definitive biography of Tsien, all I know is that the U.S. never officially charged Tsien with espionage… [and] in the end they found no convincing evidence that he was either a communist or a spy.” Space historian and journalist Jim Oberg also wrote about the inaccuracies. The CIA produced a report disputing many of the report’s key charges, although it did not address the comments about Tsien. But the most comprehensive response was produced by a group of professors at Stanford University’s Center for International Security and Cooperation, who wrote an exhaustive response to virtually all of the report’s claims. They stated that the myriad flaws that they found were not “mere nitpicks” but collectively added up to a grossly distorted picture. “The combination of factual errors, misused evidence, incorrect, misleading, or nonexistent citations, and implausible interpretative spins of existing research—interpretations that the authors of the research themselves would likely have objected to—together create a misleading impression of Chinese politics and economics,” they wrote. Alas, Fisher is still repeating these falsehoods because they suit his narrative: China is a space threat today and China has always been a threat, Tsien’s espionage proves it.

Iris Chang’s magnificent biography of Tsien Hsue-shen formed the basis for much of Aviation Week’s article justifying his selection as “person of the year” for events that he had no involvement in—this despite the fact that Chang admitted that we know very little about Tsien’s actual work on Chinese missiles and spacecraft. Nevertheless, Bradley Perrett’s feature article does make a keenly insightful observation: for several decades the nuclear-tipped missiles that Tsien helped his country build were not aimed at the United States, but at our primary enemy, the Soviet Union. In the end, Tsien had inadvertently helped the country that trained him, nurtured him, and then kicked him out. That’s something that the Cox Report, and apparently Fisher, never recognized.

Chang speculated that eventually the world would learn more about Tsien’s work on the Chinese missile and space programs, especially after his death, when his colleagues would be more likely to speak about him. She wrote that thirteen years ago, and yet the old dragon is still here, in the twilight of his life, still an enigma.