The Vision for Space Exploration and the retirement of the Baby Boomers (part 1)Is this the beginning of the end, or the end of the beginning?by Charles E. Miller and Jeff Foust

|

| Any long-term projections of NASA’s budget, and the development of a national space strategy based on those projections, needs to account for the major demographic shifts the country is facing as the Baby Boomer generation retires, and the resulting effects on federal spending. |

For years—decades, even—many space program advocates have promoted the idea that NASA should receive a slightly bigger piece of the overall federal budget. In 1990, the Augustine Commission called on the US government to give NASA a 10% per year increase for an entire decade. Similar calls for significantly more money have been heard in the last few years, as the agency has struggled to maintain the shuttle and ISS programs as it ramps up its implementation of the Vision for Space Exploration, including the development of the Orion spacecraft and Ares 1 launch vehicle. Recent efforts have ranged from calls by advocacy organizations to increase NASA’s share of the federal budget from its current 0.6 percent to a full 1 percent, to repeated efforts by Sens. Barbara Mikulski and Kay Bailey Hutchison to add an additional $1 billion to NASA’s budget, and to Rep Dave Weldon’s recent “SPACE Act” proposal that would require a several-billion-dollar per year increase to continue Shuttle flights for many more years. While such efforts are well intended, we will provide historical information suggesting there is little reason for optimism.

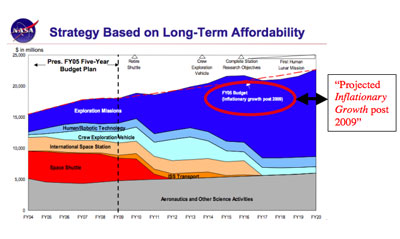

NASA and the White House have maintained less ambitious budgetary goals. When the Vision for Space Exploration (VSE) was announced in January 2004, the “sand chart” figure (below) that showed the agency’s projected spending through 2020 anticipated only inflationary growth in NASA’s budget beyond 2009. We will demonstrate that the VSE sand chart projection of even flat spending for NASA in the next decade may be optimistic.

|

Consistent with the 2004 White House budget projection, Administrator Mike Griffin has repeatedly argued over the last several years that a NASA budget that keeps pace with inflation over the long term would allow the agency to take on a number of ambitious missions. “If we make the necessary strategic investments and maintain the sense of purpose that I find around the agency today, then we can indeed be back on the Moon by 2020, have a lunar base by mid-decade, and we can be on Mars by the mid-2030s,” he said in a speech last month (see “Hoping for a reality tomorrow”, The Space Review, March 10, 2008). A year earlier Griffin predicted flat but stable top-line funding for NASA for 50 years (Aviation Week & Space Technology, March 14, 2007), stating that “the U.S. today is spending more than twice as much on civil space, per capita, as any other nation, and I believe this situation is unlikely to change significantly for some time” and that this is a “reasonable yet conservative projection”.

It is certainly reasonable and appropriate to ask for that level of financial stability, and Administrator Griffin is making a valiant effort to protect NASA’s budget. However, recent history and current major trends suggest that 50 years of flat funding for NASA is optimistic.

Any long-term projections of NASA’s budget, and the development of a national space strategy based on those projections, needs to account for the major demographic shifts the country is facing as the Baby Boomer generation retires, and the resulting effects on federal spending. As Boomers retire—and the oldest ones are already eligible for Social Security—they will put an increasing strain on the federal budget as spending on Social Security, Medicare, and other so-called “mandatory” programs grows. The first Boomers who were born in 1945 are 63 years old today, and thus already eligible for early retirement. These boomers will be 65 in 2010, and will start retiring in large numbers.

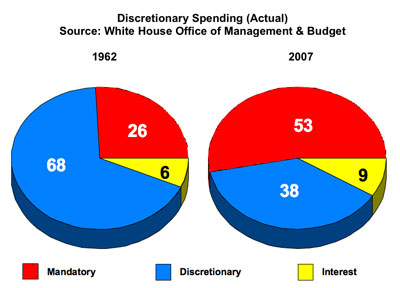

Ignoring the coming wave of Boomer retirements, mandatory spending has already grown from 26 percent of the federal budget in 1962 to 53 percent in 2007, at the expense of discretionary spending (which includes NASA as well as many other federal agencies, including the Department of Defense).

|

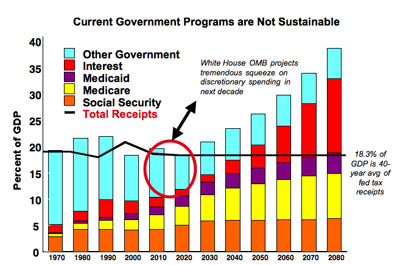

According to White House Office of Management & Budget (OMB) projections, this trend will continue, if not accelerate, in the next decade as Baby Boomers retire, making significant cuts to discretionary spending increasingly likely. As can be seen from the following White House OMB chart, released with the fiscal year 2009 budget release, the White House OMB is projecting significant cuts to domestic spending between 2010 and 2020.

|

Obviously, these long-term trends in Social Security, Medicaid, and Medicare are not sustainable, and our national leaders will be forced to do something about it. This is our point. A near-term fiscal crisis is emerging in the next decade, and solving it will be the responsibility of the next President of the United States and the US Congress.

| It is unrealistic to expect that NASA will somehow be immune to pressures to cut spending. If that happens, it will be difficult, if not impossible, for the current exploration architecture to continue in anything resembling its current form and schedule. |

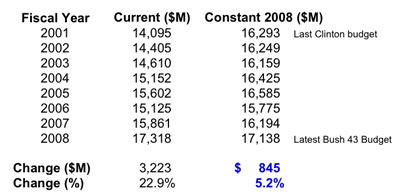

Recent history provides a taste of what NASA may be facing in the very near future. During the Bush Administration NASA has done reasonably well in terms of spending: its budget, in constant 2008 dollars, has increased from $16.3 billion in fiscal year 2001 (the last Clinton Administration budget) to $17.1 billion in fiscal year 2008. This 0.7% real increase per year, on average, is far short of the increases that many space advocates have been seeking, but it is better than what some other agencies have received during the same period. However, this small budget increase has taken place during a time when balancing the budget has not been a priority for either a Republican President or the U.S. Congress.

Sources: Budget Data: http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/fy2009/hist.html Inflation Index: http://cost.jsc.nasa.gov/inflation/nasa/inflateNASA.html Credit also to anonymous posters on www.spacepolitics.com. See http://www.spacepolitics.com/2008/02/28/bill-clinton-hillary-supports-human-spaceflight-just-like-me/ |

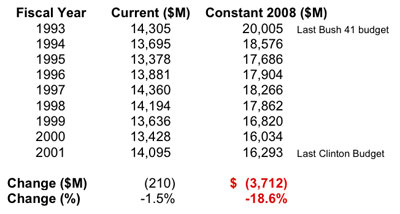

By comparison, during the Clinton Administration, when both the Democratic White House and Republican Congress sought (and achieved) a balanced budget, NASA fared far worse: in constant 2008 dollars, its budget fell from $20 billion in fiscal year 1993 to $16.3 billion in 2001, a decline of nearly 20 percent. Considering the budgetary challenges created by the retirement of the baby boomers, the next graph may be a better guide to the austerity NASA will face in the years to come than its experience of the last few years.

|

These fiscal pressures will force the next president—regardless of whoever is elected in November—to make some hard decisions in the years to come about discretionary spending. It is unrealistic to expect that NASA will somehow be immune to pressures to cut spending. A budget cut in the next Administration that is equivalent to last decade’s cut would result in reduction of NASA’s budget of over $3 billion per year. If that happens, it will be difficult, if not impossible, for the current exploration architecture to continue in anything resembling its current form and schedule. It will be significantly delayed, radically altered, or even cancelled.

Should that happen, is there a way to keep the Vision for Space Exploration alive?

Is there a realistic and credible strategy that will allow us to simultaneously re-invigorate aeronautics research, to meet the critical challenges to understand the science of climate change, to aggressively search for life around other stars and in our own solar system, and to also execute the Vision for Space Exploration?

Perhaps of most interest to the readers of The Space Review: is there a national space strategy, easily understandable by the American people and our elected leaders, that will deliver clear and specific benefits to national security, to the national economy, and to science, and therefore help NASA defend itself from major budget cuts even in an era of budget cutting?

The answer to all these questions is “Yes”.

To be continued in Part 2.