NASA and space solar powerby Taylor Dinerman

|

| NASA will resist being forced to spend money on projects that it does not see as falling within its missions of science and exploration. |

Technology development in general has been cut back. The NASA Institute for Advanced Concepts has been closed. There is a minimal ongoing effort to build up some technologies that may in the future be useful for reusable launch vehicle development, but it is hard to see how this fits into a coherent future program. The agency has its priorities and is ruthlessly sticking to them.

NASA is not the US Department of Spatial Affairs: it does not have the statutory authority to control, regulate, or promote commercial space activities such as telecommunications satellites, space tourism, space manufacturing, or space solar power. Such powers are spread throughout the government in places like the FAA’s Office of Commercial Space Transportation, the Department of Commerce, and elsewhere. Even if NASA were somehow to get the funds and the motivation to do space solar power, these other institutions would resist what they would recognize as an encroachment on their turf.

Until the shuttle is retired and NASA has a new and secure method of getting people into space, either with the Orion capsule on top of the Ares 1 or perhaps another rocket, or using the SpaceX Dragon capsule and Falcon 9 combination, there is no room for any other major programs. It will require all they can do to cope with their current programs and to deal with a new president and his or her administration. They don’t need any more distractions right now.

Eventually NASA will have to play a role, even if a small one, in the development of space solar power. The best option is that it will be as part of an interagency process directly supervised from the White House, with lots of Congressional and private sector input. The debate on this new energy source has hardly begun and these are lots of very smart people with very strong opinions on the subject.

At some point within the next four years the president is going to have to decide whether to go ahead with this new and potentially unlimited source of energy or to put it back into limbo. The case for it is growing stronger every time the price of oil goes up or, more to the point, every time we suffer from a blackout or a near-miss. For example, a couple of months ago many large electric customers in Texas were asked to shut down their operations because there was not enough wind to spin the numerous wind turbines that have been sprouting up all over that state.

| The case for space solar power is growing stronger every time the price of oil goes up or, more to the point, every time we suffer from a blackout or a near-miss. |

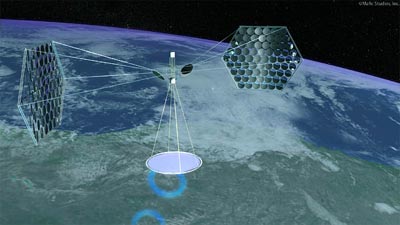

Obviously space solar power could provide a reliable, non-polluting, and very large-scale source of energy. The biggest question is, can it be done economically? Frankly, with its history of problematic cost estimates, NASA (or any other government institution) is not going to provide us with a trustworthy answer. The decision to go ahead will be a shot in the dark. If we can clearly see that low-cost access to space via the private sector is going to be a reality, then whoever is president will have a solid basis on which to proceed.

If SpaceX’s Falcon 1 rocket succeeds in the next launch, then there is hope that space solar power can be made to work economically within a reasonable time frame. If not, then it will be even harder to sell the whole idea.