Blocked sale exposes the neglect of Canada’s space programby Chris Gainor

|

| The most positive impact of the MDA’s attempt to sell was that during the four months since the sale was announced, many voices were raised about the neglect of Canada’s 50-year-old space program. |

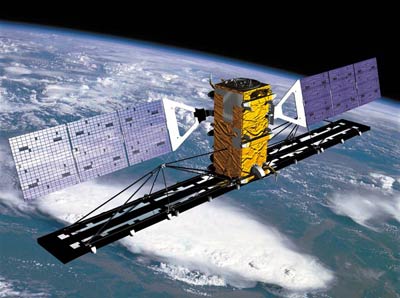

Canada’s space crisis broke suddenly on January 8, 2008, when MacDonald Dettwiler and Associates Ltd. (MDA) of Vancouver B.C., Canada’s largest space contractor, announced that it was selling all of its space operations to Minnesota-based Alliant Techsystems Inc. (ATK) for $1.3 billion. MDA is the corporate home of the shuttle remote manipulator system, the ISS Mobile Servicing System, RADARSAT-2, and much of Canada’s communications satellite contracting work. (See “Canada’s space program in crisis,” The Space Review, January 28, 2008)

The following day, the Canadian government announced that the CSA’s president, Laurier Boisvert, had resigned a few days earlier after just nine months on the job. Boisvert was supposed to restore leadership to the agency that had been missing since former astronaut Marc Garneau had stepped down from the president’s job in 2005.

These events set off a controversy as many Canadians expressed their fears that the core of Canada’s space program would be lost. Opposition political parties denounced the sale, and parliamentary committees began holding hearings on MDA’s plans. Canadian trade unionists and from peace activists who had rarely spoken about Canada’s space program lined up against the MDA sale because of ATK’s role as a manufacturer of land mines and other arms.

Much of the controversy focused on the fact that RADARSAT-2 is operated on a joint basis between the government and MDA, and the satellite is used by Canada’s military to monitor Canada’s shoreline and arctic islands. The prospect of RADARSAT-2 falling into American hands became a flashpoint for Canadian nationalists. Although Canada’s Conservative Party government is friendly with the Bush Administration, the two governments have publicly differed over control of passages between Canada’s arctic islands.

In April, Industry Minister Prentice announced that he was considering blocking the MDA sale, an announcement that surprised many people because of the close links between his government and the business community and because Conservative and Liberal Canadian governments had not rejected a foreign takeover of a Canadian business in more than two decades. Late on May 8, Prentice confirmed that the government would block the sale. Although MDA shareholders had overwhelmingly supported the sale to ATK, MDA management indicated that the firm will continue in the space business for the time being.

The most positive impact of the MDA’s attempt to sell was that during the four months since the sale was announced, many voices were raised about how the neglect of Canada’s 50-year-old space program in recent years threatens its future and the jobs of thousands of Canadians.

With the launch last December of RADARSAT-2, the impending end of the shuttle program in 2010, and the installation in March of the final segment of the Mobile Servicing System on the ISS, MDA was seriously short of new business. Critics pointed out that programs such as Radarsat Constellation, the follow-on to RADARSAT-2, are becalmed due to government neglect.

MDA founder John MacDonald complained that MDA has lost valuable contracts to help build the European Space Agency’s ExoMars rover because the Conservative government declined to take part in the project. Canada is taking part in the Mars Phoenix mission, but the previous Liberal government turned down Garneau’s plans for Canadian participation in NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory, along with his proposal for a Canadian Mars mission (see “A Maple Leaf on the Red Planet,” The Space Review, February 23, 2004).

Since Canada seemed to have no new space ambitions, MDA was forced to look south for business, and according to MacDonald, the door was closed because of American security regulations, forcing MDA to try to save its space business by selling it. While other Canadian space firms differed with MDA, saying it is possible for Canadian space contractors to make sales in the in the United States, the Canadian government heard loud and clear that it would have to use the Canadian space industry or lose it. The MDA sale raised for the first time ever a public discussion about the role of Canada’s space program in national security. (See “Small satellite builders: a tale of two mergers,” The Space Review, April 21, 2008)

Prentice has responded by taking modest first steps to restore Canada’s space program. On March 31, he set up an advisory committee headed by the President of the University of Alberta to review Canada’s space program. Shortly after blocking the MDA sale on May 8, Prentice announced that MDA will get a four-year, $109-million contract for service work on the ISS’s Canadian-built Mobile Servicing System, renewing an existing contract.

Setting up an advisory committee and renewing a contract are easy. Now Prentice and the Canadian government will have to make decisions about Radarsat Constellation and Canadian participation in NASA and ESA Mars programs.

In addition, Canada’s future in human space flight remains open to question beyond next year’s flights of a Canadian astronaut on the shuttle and another on Soyuz for a long-term stay on the ISS. Although the CSA is about to hire new astronauts, no role for Canada in NASA’s Constellation program has been established.

| The aborted sale of MDA placed Canada’s space program on the political agenda for the first time since the CSA was formed in 1989. |

Prentice has promised to “work diligently to ensure American markets are available to Canadian companies,” and this promise is probably based in part on the hope that the administration and congress that take office in Washington next year will move away from the post-9/11 policy direction of slapping new security restrictions on trade without regard for economic consequences.

Above all, the CSA needs new leadership, and the Canadian government needs to pay attention to that leadership and renew Canadian space efforts with increased funding to make up for diminished government support in the past decade.

“I think the lack of leadership in space for Canada has had consequences on our ability to fulfill our ambitions,” said John Keating, the CEO of another leading Canadian space contractor, COM DEV International.

The aborted sale of MDA placed Canada’s space program on the political agenda for the first time since the CSA was formed in 1989, and has provided a warning of the consequences of continued neglect of the space sector by the Canadian government. Canada’s space program has been a source of pride for Canadians and a success in terms of generating business for Canadian high technology firms. Now Canada has been put on notice that these successes will not continue without governmental action.