Space solar power and the Khyber Passby Taylor Dinerman

|

| In the longer run Pakistan’s closure of the Khyber Pass supply route justifies investment in SSP as a technology that landlocked nations can use to avoid the pressures and threats that they now have to live with. |

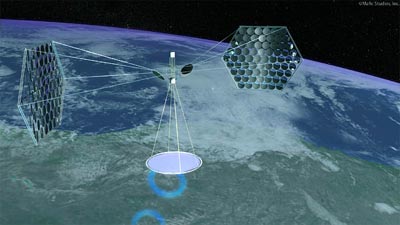

Last year the National Security Space Office released its initial report on space solar power (SSP). One of the primary justifications for the project was the potential of the system to provide power from space for remote military bases. Electrical power is only part of the story. If the military really wants to be able to operate for long periods of time without using vulnerable supply lines it will have to find a new way to get liquid fuel to its forward operating forces. This may seem impossible at first glance, but by combining space solar power with some of the innovative alternative fuels and fuel manufacturing systems that are now in the pipeline, and given enough time and effort, the problem could be solved.

The trick is, of course, to have enough raw energy available so that it is possible to transform whatever is available into liquid fuel. This may mean something as easy as making methanol from sugar cane or making jet fuel from natural gas, or something as exotic as cellulosic ethanol from waste products. Afghanistan has coal and natural gas that could be turned into liquid fuels with the right technology.

What is needed is a portable system than can be transported in standard containers and set up anywhere there are the resources needed to make fuel. This can be done even before space solar power is available, but with SSP it becomes much easier.

In the longer run Pakistan’s closure of the Khyber Pass supply route justifies investment in SSP as a technology that landlocked nations can use to avoid the pressures and threats that they now have to live with. Without access to the sea, nations such as Afghanistan are all too vulnerable to machinations from their neighbors. Imagine how different history would be if the Afghans had had a “Polish Corridor” and their own port. Their access to the world economy might have changed their culture in positive ways. Bangladesh and Indonesia are both Muslim states whose access to the oceans have helped them adapt to the modern world.

In Africa some of the poorest nations tend to be landlocked. Some, like Botswana and to a lesser extent Uganda, try and make up for this disadvantage by having relatively decent governments. Others are have simply fallen victim to regional violence. Some coastal nations such as Nigeria and Angola, which have abundant oil, have seen the money produced disappear into the pockets of corrupt officials or just wasted. On the other hand South Africa, which has huge coal reserves, has not done badly.

Clean and plentiful energy from space will not solve these problems anymore than having lots of oil solved the problems of places like Nigeria, but it may be an essential part of the development process for poor landlocked nations. It will take a long time for this technology to become available, but there are few, if any realistic alternatives.

| In today’s climate of economic uncertainty, it may seem strange to want to focus on problems that both the US military and very poor nations will be facing 15 or 20 years from now, but that is what true visionary leadership is all about. |

Major developing nations such as China and India will be able to gain access to SSP without too much trouble. It is the smaller and poorer nations of what has been called the “Fourth World” that will need it the most and be least able to afford it, at least in the early stages. This is why the development process should be done in such a way as to provide at least some of these nations—the ones who show a commitment to good government—with experimental receiver stations. They can contribute to the process by making an investment of time, space, and effort rather than cash. This could be recognized at a later date by giving them access to SSP at a discount.

In today’s climate of economic uncertainty, it may seem strange to want to focus on problems that both the US military and very poor nations will be facing 15 or 20 years from now, but that is what true visionary leadership is all about. Energy insecurity has been and will continue to be a driving factor in world affairs. For very poor nations, space solar power may allow them to escape form the economic chains forged by geography. In turn this may promote long-term prosperity that can be sustained over many decades.

Economic and political isolation is just as bad for a nation as it is for a military force. Space-enabled communications long ago ensured that control of landlines of communications would not enable states to cut off their landlocked neighbors from all but vulnerable radio communications with the outside world. SSP can do for energy what communications satellites did for information, for the poorest of the poor. In many ways the people of Afghanistan are just that, and this may be the best thing that 21st century technology can do for them.