Space policy 101: civil space 2009by Dwayne Day

|

| For the civil spaceflight part of the symposium numerous space policy experts indicated that NASA’s bold plans for the future of human spaceflight were all on hold until after a high-level independent review is finished later this summer. |

The symposium featured nearly two dozen speakers and covered both civilian and military space topics. Because the focus was on government space programs, there was relatively little discussion of NewSpace topics. Although not really surprising (NewSpace represents not only a tiny fraction of government space procurement, but also a very small fraction of the space industry as a whole), it did serve as a stark reminder that what the space-involved public is so passionate about is not what the majority of the people with the money or the power to direct space programs care about.

What follows is a summary of most of the talks at the symposium. This is more of a narrative than a subject-specific account. It is best read as an overview of the significant space policy issues as recognized by the people who control and who observe space policy in the United States today.

Scott Pace, director of the Space Policy Institute, started the symposium by discussing the erosion of NASA’s budget over the years since the Vision for Space Exploration was first unveiled in January 2004. He said that the cumulative effects of cuts resulted in $11.7 billion in reductions since that time. He noted that although NASA received a substantial boost this year in the latest budget, the space agency will lose $3 billion in the out years. So for NASA, aligning its policies with a budget that is heading downward will be a major challenge.

But Pace also pointed out that the charter for the Review of US Human Space Flight Plans Committee (i.e. the Augustine Committee) allows the committee to say whether or not NASA has the money it requires to conduct the mission it has been given, and so there is the possibility that the out-year budget slump could be reversed.

Having set the stage, Pace introduced the first speaker, someone who is not widely recognized outside of Washington as a major player in establishing American space policy.

The operational arm of earth sciences

The first speaker was Mary Kicza, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Assistant Administrator for Satellite and Information Services. NOAA is responsible for weather and water information, managing fisheries and maritime commerce—a portfolio that ranges far beyond operating satellites. But NOAA’s space budget and activities are substantial, and vital to the nation’s well being.

According to Kicza, NOAA currently has a brighter budget outlook than NASA. The agency received $4.5 billion in Fiscal Year (FY) 2010 and has 12,600 employees—approximately two-thirds as many employees as NASA with about 25% of the budget of the space agency (the difference can be explained by NASA’s procurement of very expensive pieces of hardware). According to Kicza, NOAA currently operates 16 spacecraft, 9 ships, and 12 aircraft.

Kicza provided an overview of NOAA’s current activities. NOAA spends approximately $1.4 billion on satellite and information services, whereas NASA spends essentially the same amount on Earth sciences.

Kicza said that the agency will soon launch the GOES-O geostationary weather satellite—hopefully in late June—which is the second of the “N-O-P-class” spacecraft. GOES-P will be launched next year. A normal weather satellite constellation consists of two active satellites and one spare. Although NASA—which acts as a procurement agent for NOAA—awarded a contract for the GOES-R class of satellites to Lockheed-Martin in December—that contract decision is currently being protested by Boeing, which lost the bid.

| Kicza said that NOAA is involved in discussions concerning a “national climate service.” She said that it is clear that no government agency can handle everything in this area and it is still unclear what the evolution of such a service will be. |

NOAA also operates the Polar Operational Environmental Satellites, or POES. These satellites operate in low Earth orbits and provide up-close mapping and weather predictions required in part to calibrate the higher orbiting satellites. The last spacecraft of this type launched was NOAA-19 (formerly NOAA-N Prime), which is operating properly in orbit, giving NOAA five operational satellites. The POES series is scheduled to be replaced by the National Polar Orbiting Environmental Satellites, or NPOESS. NPOESS has run into severe development problems, however. Kicza did not dwell on the subject of NPOESS, and a discussion of all that has gone wrong with that project would have taken its own symposium.

On the subject of current policy issues, Kicza said that NOAA is involved in discussions concerning a “national climate service.” She said that it is clear that no government agency can handle everything in this area and it is still unclear what the evolution of such a service will be. Right now NOAA is concerned with finding homes for the climate sensors that were removed from the NPOESS platforms when it was de-scoped several years ago in order to reduce cost and complexity. NOAA and NASA are seeking to put the sensors on other platforms, preferably small satellites that can be built and launched relatively quickly.

Kicza said that whereas NASA conducts Earth science research, and NOAA conducts operations, there is a gap between them that is always challenging to bridge, but she cited several examples where NOAA is not only cooperating with NASA, but with other countries and space consortiums. For example, the new budget contains $23 million for the Jason-3 spacecraft, a collaboration between NOAA, the European meteorological satellite consortium Eumetsat, and the French space agency CNES, will be launched in 2013, allowing it to overlap with Jason-2, something that is necessary for sensor calibration. This will continue 17 years of continuous ocean altitude measurements started with the Topex-Poseidon satellite, continuing with Jason-1 and the current Jason-2.

NOAA is also interested in developing a follow-on to the successful Advanced Composition Explorer (ACE) satellite, which samples low and high-energy particles in space, which is important because of the effects of “space weather” on other satellites as well as various terrestrial operations such as airline flights and electricity transmission. One possibility is refurbishing the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) satellite, originally developed as Triana and in storage for nearly a decade. NASA owns DSCOVR and could provide the satellite to NOAA to refurbish, with DoD providing the launch. An alternative is a commercial purchase of a follow-on spacecraft.

Kicza also mentioned the Quickscat satellite, which has proved to be important for marine weather forecasting, and said that NOAA may fly an instrument on a Japanese spacecraft as a follow-on. She said that NOAA is currently looking into Taiwan’s GPS radio occultation program that measures the changes in radio signals received from GPS satellites. Measuring these changes provides useful space and atmospheric weather information.

One member of the audience wanted to know what NOAA does in the area of information security. NOAA’s satellites are national assets—the loss of a weather satellite, or the disruption of ocean and atmospheric data, could have significant negative effects upon the American economy and population. The Chinese ASAT test of early 2007, where the Chinese destroyed one of their own obsolete weather satellites, created significant orbital debris in an orbit that is also used by American weather satellites. Kicza explained that every three years NOAA’s systems are subjected to detailed scrutiny, including penetration exercises, to identify potential vulnerabilities to attack. She said that NOAA is concerned about the orbital debris issue and other potential threats, but that the agency has limited ability to defend against them and is working with the Department of Defense and others to try and understand the threat.

Another topic that was raised several times during the day concerned how the government will respond to the Obama Administration’s proposed “cap and trade” policy for carbon emissions, as well as a possible international treaty concerning greenhouse gas emissions. Both domestic regulations as well as international treaty verification will require new space-based platforms for monitoring the gasses. Not all of the questions were directed at Kicza, but it is clear that the federal government is only beginning to think about how such broad-reaching policies and/or a treaty would require new space assets that are not currently designed or funded. The recent launch failure of the Orbiting Carbon Observatory only adds to the murkiness surrounding this issue, because OCO would have provided a useful demonstration of what space platforms could contribute to environmental monitoring for purposes of regulation, as opposed to science.

Civil space programs: Waiting for Godot

Next came a panel discussion involving four experts on the civil space program, although as one would expect, the most insightful and thought-provoking commentary came not from government bureaucrats, but from those who had a little more freedom to speak. First to speak was Paul Shawcross, chief of the Science and Programs Branch of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB), who addressed the topic raised by Scott Pace at the beginning of the symposium—what is going to happen to NASA’s budget in the next several years. Shawcross noted that the reason that NASA’s out-year budgets are flat is because OMB is anticipating increases in Social Security, Medicare, and Defense, among other areas. That, and deficit reduction, is going to force cuts from the rest of the domestic discretionary spending programs, like NASA.

Shawcross was followed by Damon Wells, a senior policy analyst in the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). Wells noted that although the Obama administration has indicated that its priorities are the economy and health care, it has also made a clear commitment to increasing support for science and technology. NASA received $18.7 billion this year, 5% more than in 2009. NOAA’s budget also increased as well. He said that NASA received $4.48 billion for science, including an increase in the Earth sciences budget. But he also noted that NASA would probably face a constrained budget in the next several years.

Michael Hawes, NASA’s associate administrator for Program Analysis and Evaluation, said that at the beginning of 2009 the agency expected a confusing budget year compared to the normal process. This was because of the new administration wanting to set its own priorities. However, the economic stimulus bill only added to the confusion. He added that “the budget integration task has been enormous.” Hawes noted that “historically, NASA has done badly the first budget of new administrations,” which makes the current situation, where the agency finds itself with a billion dollars more than it had last year, so surprising.

| “Exploration obviously is the elephant in the room,” Hawes conceded. The agency requires an “integrated plan for exploration” that not only considers where the agency is going and how, but also includes the ISS program as well as related issues like workforce. |

Hawes noted that there has long been strong congressional interest in aeronautics at NASA, but no long-term commitment. That appears to have changed, and so aeronautics may be due for a long-term boost, with research funding in areas such as “green aircraft” technologies. He also said that NASA still believes that they can retire the shuttle by the 2010 date and the budget is coordinated with that goal.

“Exploration obviously is the elephant in the room,” Hawes conceded. But this involves more than simply funding the existing programs for returning Americans to the Moon. The agency requires an “integrated plan for exploration” that not only considers where the agency is going and how, but also includes the ISS program as well as related issues like workforce. Right now, a number of NASA activities related to exploration are suspended as the Augustine Committee gets underway. Hawes’ office is set up to support the committee. He said that starting in mid-June the panel will have a series of fact-finding telecons, site visits, and public meetings. “So the rest of my summer is trashed,” he joked.

What Hawes did not focus upon, but which is apparent to everyone who is familiar with NASA’s planning process at the moment, is that this review has essentially resulted in NASA’s exploration planning and space station planning being put on hold until Norm Augustine and his committee can produce their report. Most Ares V and Altair work has been suspended until the review is completed, and major questions about what to do with the International Space Station after 2016 have also been put on hold. NASA’s policy and analysis experts have stopped doing much of their normal work in order to support the committee. As a result, many of these projects are going to have their schedules suspended until the fall at the earliest, and possibly until the next budget emerges in February or March 2010.

Hawes concluded his talk by noting that NASA’s supporting activities don’t get much public attention, but include such important issues as spectrum management (i.e., making sure that NASA’s spacecraft don’t interfere with the signals of other satellites and communications systems, and vice versa), communications support for the agency’s missions, and interoperability between systems.

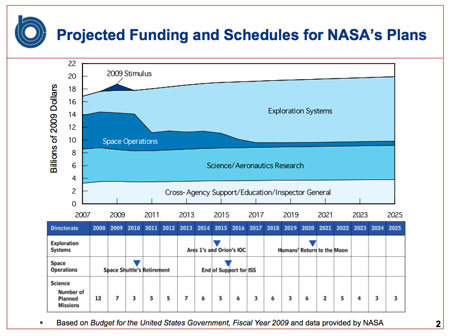

Kevin Eveker, an analyst with the National Security Division of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), spoke about the budgetary implications of NASA’s current plans. He primarily discussed the findings of a report produced by CBO several months ago. Eveker’s talk included a budget chart demonstrating how NASA’s major activities are divided up into exploration, space operations, science and cross-agency support. The chart indicates that once shuttle operations cease, exploration systems will dominate the agency’s budget over the next several years.

NASA’s projected budget and schedules, divided by major account. (credit: CBO) |

The last speaker on the panel was Marcia Smith, president of the Space and Technology Policy Group and well-known for her previous work for the Congressional Research Service and the National Research Council’s (NRC) Space Studies Board. She said that she is enjoying being able to speak her mind at such a forum, and as the only non-government employee on the panel, she also had the most interesting insights about current space policy.

Smith noted that the US government currently spends a large amount of money on space. In addition to NASA’s budget, the DoD and classified intelligence space budgets are also large [Author’s note: combined, they are apparently significantly larger than NASA’s total budget]. She said that a key question that everybody should ask is whether bigger budgets are necessary, “or should we spend money more wisely?” While the people involved in space policy would clearly prefer more money, not everybody in government agrees that they should get it.

Smith said that a 2006 NRC report on balance in the space science budget concluded that NASA was trying to do too much in the space sciences with too little budget to accomplish it. [Author’s note: the 2003 Columbia Accident Investigation Board report concluded the same thing for NASA’s human spaceflight program.] Smith asked if anything has really changed in the intervening years. “You really cannot plan a program based on the hope that Congress will give you more money,” she said. “Hope is not a strategy.” She then quoted Tom Young, former Martin Marietta CEO and the chairman of innumerable military and civil space policy reviews, who said of NASA that “the current system is designed to maximize the number of programs that are started—and minimize the number that are completed.”

According to Smith, there are two steps to realigning NASA’s budget and its programs. The first step is controlling the costs of current programs. She showed a list indicating that NASA’s current budget is allocated as follows:

54% for human spaceflight

24% for space science

18% for cross-agency support

3% for aeronautics

0.6% for education

The second step, according to Smith, is determining priorities. The NRC’s “decadal surveys” determine ten-year priorities for space science disciplines and for aeronautics based upon the consensus reached by the relevant communities. Right now the NRC is undertaking decadal surveys in astronomy and astrophysics, planetary exploration, and life and microgravity sciences, and NASA is currently starting to implement the priorities established in the first Earth sciences decadal survey completed two years ago.

Although the space sciences have a mechanism for establishing priorities, human spaceflight does not. Turning her attention to Michael Hawes’ elephant in the room, Smith emphasized that the Augustine Commission will help set priorities, but will not actually set those priorities. Right now it’s not clear who will, or when. The committee’s “aim is to identify and characterize a range of options,” not set priorities.

| Smith emphasized that the Augustine Commission will help set priorities, but will not actually set those priorities. Right now it’s not clear who will, or when. |

Smith also expressed some skepticism about the ability of a small blue ribbon panel with a short time frame to develop what needs to be a consensus opinion. Will the review actually settle the debate? Not everybody agrees on either the committee’s mandate or timing. Smith quoted Senator Richard Shelby, who recently said that “instead of providing Constellation with funds to move forward, [the FY2010 budget] is delaying the current mission while seeking to have a do-over of plans that have been authorized by both Republican and Democratic Congresses.”

Smith then listed several questions that she hopes the panel will address:

- Why is the 2020 lunar landing date important? (i.e., why not some other date?)

- Does the humans-to-Mars paradigm still resonate with the public, and will it still resonate with the public by the time we can actually conduct it?

- How can NASA avoid promising more than can be delivered?

- What is to be done with the International Space Station now that it is nearing completion? Shouldn’t we use it?

With regards to the last question, Smith said that when she was writing about the space station at the Congressional Research Service during the 1980s and 1990s, it was inconceivable to her that the United States would build a space station and then not actually utilize it, but that is the situation that the agency is apparently facing now. She noted that numerous scientific reviews of the station have indicated that the primary research tool required for the station to be relevant to life and microgravity science is a centrifuge, and NASA decided years ago not to build a centrifuge module.

Smith said that one question she has is whether instead of re-doing what the agency did in the 1960s, NASA should focus on developing technology for self-assembling laboratories and habitats that can unfold and construct themselves on planetary surfaces so that they would be waiting when the astronauts arrived. She noted that such an approach would allow crews to land and immediately stay for months, not days. It would also allow them to do exciting things from the start, rather than spending a lot of time on construction. It would engage a younger generation interested in robotics and new technologies. And finally, it could produce valuable spinoffs on Earth.

Smith said that there are some important questions in the space policy field right now. First on the list is who is in charge? Where is the National Aeronautics and Space Council that was discussed during the election? Such an organization is vital, she believes, to bringing in all the actors, particularly industry, to discuss important policies. Another question is whether or not we need a national space strategy to implement the national space policy.

Finally, Smith said that the third step in aligning budgets and policies was sticking to the priorities unless they crossed a “tripwire.” She said that this means canceling what does not fit the budget, such as the Department of Defense’s TSAT program. Congress has established some tripwires for DoD and NASA programs. But clearly not enough has been done in this area, and once programs are started they are very difficult to cancel.