Reality bites: the future of the American human spaceflight endeavorby Rodger Handberg

|

| That is the fate of the American human spaceflight program: great expectations and limited resources. What causes consternation presently is that the Obama Administration is willing to publicly say that the emperor has no clothes. |

As a product of the first space age immediately after Sputnik in 1957, NASA has long labored under the burden of achieving great feats in its infancy while in more recent years the program has labored under the burden of great expectations but limited resources, especially for the task the agency most fervently wished to pursue: human exploration beyond Earth orbit out into the solar system. What existed and continues to exist is the great disconnect between what program is aspired to by the agency and what is in fact supported. If one looks back over the past forty or so years, the consistent pattern is one of inconstant support. Repeatedly, major projects in all areas across the agency are initiated or more likely proposed but if approved are cut back, stretched out, or terminated after starving for a few years.

That is the fate of the American human spaceflight program: great expectations and limited resources. What causes consternation presently is that the Obama Administration is willing to publicly say that the emperor has no clothes. That is a radical concept, but one that grows directly out from the realities of how NASA and the human spaceflight program has been treated politically and economically. Supporters of human spaceflight have tended to ignore this reality because the white knight is on the way; that is, the next president will be the one to save the program by ignoring political reality and adding significantly more money to NASA programs. The record is clear: that is not going to happen unless a major shift occurs in the external political environment that demands an enhanced human spaceflight program to save or ameliorate the crisis.

This record, however, refers to government-funded and -directed programs, not the private sector, which is partially sheltered from the problem as long as they are not dependent on government subsidies or contracts. Unfortunately, too often, private space advocates have spoken out of both sides of their mouths, ripping government programs as inefficient and flawed but on the other hand demanding government subsidies either directly or by transferring government-developed technologies to their control, usually with some start up money thrown in to make things go more smoothly. The Obama changes will not end this disconnect between private and public although some act as if the tentative steps being suggested are ending the world in a giant bonfire of the vanities. That is a matter for another day; the question here is how to view the historical record and what conclusions can be drawn.

| Repeatedly, major projects in all areas across the agency are initiated or more likely proposed but if approved are cut back, stretched out, or terminated after starving for a few years. |

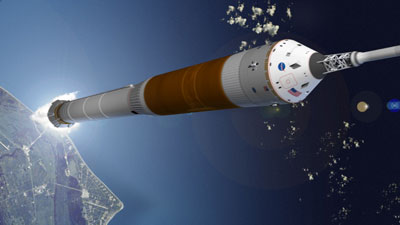

As former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich and former Congressman and Chair of the House Science Committee Robert Walker wrote recently in the Washington Times, “The launch-vehicle portion of the Constellation program was so far behind schedule that the United States was not going to have independent access for humans into space for at least five years after the shutdown of the shuttle. We were going to rely upon the Russians to deliver our astronaut personnel to orbit. We have long had a cooperative arrangement with the Russians for space transportation but always have possessed our own capability.” This statement effectively summarizes why the Obama Administration decided to move in the direction that they chose. It was not an aberration but a decision grounded in the realities of the American space program, stagnant budgets, and burgeoning aspirations. What is lost in much of the discussion is that the NASA budget will receive a $6 billion boost over the short term.

The record

History does not necessarily teach us anything but it does provide a glimpse at how certain problems were handled—or not—in the past. From those historical events, one can draw certain conclusions or patterns that may distress but also enlighten. Rather than delve into a lengthy series of case studies, one might consider the following highly condensed chart of the realities of human spaceflight within the context of American politics. Several items are included because they were impacted by the decisions made with regard to human spaceflight. The reality since 1961 is that for NASA leadership, regardless of administration, Republican and Democratic, human spaceflight remains the engine of the space program with everything else secondary or more likely supportive, such as space science missions. Thus, as a result, the path for the entire federal space program has been a roller coaster not because cuts were always imposed from outside the agency (although some were) but those agency missteps, especially budgetary, with regards to human spaceflight often had immediate and disruptive consequences in other areas of the agency. For example, the decline of the aviation side of NASA especially after the supersonic transport program was terminated in March 1971 was accentuated later in the 1970s by the agency fixation on getting the shuttle launched. The more famous understanding comes from James Van Allen’s 1986 article in Scientific American lamenting the “slaughter of the innocents” in his view: the space science missions were terminated, stretched out, or forced onto the shuttle in order to expand its launch manifest. The driving issue was achieving shuttle flights.

Table of Historical Events (condensed)

| Event Date (approximate) | What Occurred | Importance and Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1958 | Mercury program | Established US human spaceflight program, Flew in 1961after the Soviets, overcame President Eisenhower’s objections |

| 1961 | Apollo Announcement | JFK set in motion Moon landing, successful landing on Moon 1969, program stopped early, 3 flights cancelled |

| 1964 | Post Apollo Applications Program | Follow on to Apollo using Saturn equipment, effectively terminated in 1967 by Congress although Skylab missions flew in 1973–74 |

| 1969 | Space Task Force | Proposed 3 levels for future human spaceflight programs including on to Mars—Act 1, rejected by President Nixon |

| 1972 | Shuttle decision | Replace Saturn as human spaceflight vehicle, approved by President Nixon, poor funding plan as remnant of 1969 Space Task Force projections |

| 1978–1981 | Shuttle development | Overcoming technical issues and budget problems, “slaughter of the innocents”: damage to space science in its Golden Age |

| 1984 | Space station decision | Next logical step—Step 2, (shuttle step 1), budget overruns, redesigns plague program |

| 1987 | Challenger Accident | Exposes danger of shuttle flight, shuttle repairs and upgrades—whether problems solved unknown |

| 1989 | Space Exploration Initiative | Long range human spaceflight program—on to Mars—Act 2, died without serious congressional action or review |

| 1991 | Mission to Planet Earth | Systematic observations of Earth; environment program to deflect political pressure for more immediate environmental policy changes, continual funding issues |

| 1993 | Space Station Freedom Revision – Clinton | Attempt to rescue failing program, transformation into International Space Station |

| 1993–1994 | Establishment of United Space Alliance | Attempt to control shuttle costs, consolidation of contracts |

| 1996 | Shuttle Replacements | X-33, National ero Space Plane, Space plane (2000), failed efforts at shuttle replacement |

| 2001 | ISS Revision – Bush | Attempt to rescue failing program, reduced and modified program, “Station complete” |

| 2003 | Columbia Accident | Déjà vu all over again, Shuttle now declared experimental |

| 2004 | Vision for Space Exploration | Set course for Moon & Mars—Act 3, replace shuttle, set future directions with possible budget, end ISS by 2015–2016 |

| 2010 | Obama and the Flexible path | Fix budget and technology issues, flexible path, future unknown, ISS extended to 2020 and beyond? |

What the above table attempts to do is identify critical points in the US space exploration program when events both physical and political intervened to change the direction pursued by NASA. Some changes were major, as in 2004 with the Vision for Space Exploration (VSE), while others were continuations or elaborations of established trends, such as the stripping of funds from space science budgets to support shuttle development at the end of the Carter Administration and effectively again in the aftermath of the VSE initiative. In sweeping terms, one can observe that several of the trends occur somewhat separately from each other: the primary quest is to keep human spaceflight alive despite what appears to be a difficult flight system, the space shuttle, declared to be experimental and dangerous. None of the major program initiatives, including Apollo, were assured of stable and continuing funding: the Apollo program was repeatedly cut as the Vietnam War and the War on Poverty began to eat into the federal budget. Prior to his death, President Kennedy proposed to significantly alter the Apollo program by converting it into a joint US-Soviet lunar landing program. The Soviets failed to respond, seeing the proposal as a trap.

Problems

NASA’s attempts to further expand its human spaceflight effort have repeatedly floundered on the unwillingness of administrations and congresses to keep their funding stable and, more critically, expanding. Instead, the space program continually suffered cuts and stretch-outs. New initiatives are funded well for a time and then they fall into the pit of “politics as usual”, meaning everything is up for grabs, including adding earmarks. The NASA budget has been repeatedly damaged by earmarks for programs. For example, from FY 1997 to FY 2006, the number of earmarks rose from six to 199. The point is that NASA as an agency and its programs are not, and have never been, immune to the impact of normal congressional politics. The result has been a consistent pattern of inconstant support—projects are started or more likely proposed but even if approved are eventually cut back and stretched out. The question is why does this occur?

The reasons are fairly simple but telling. First, political support for human spaceflight remains a mile wide and an inch deep in terms of the American public. There exist pockets of committed political support for an expansive human spaceflight program but they are dramatically outnumbered by adherents to other equally important and sought after programs, such as environmental and education funding, veterans’ benefits, and money for science and technology. Universities, for example, are cross pressured by their support for the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and NASA, the first two being more important to most universities.

| The point is that NASA as an agency and its programs are not, and have never been, immune to the impact of normal congressional politics. The result has been a consistent pattern of inconstant support—projects are started or more likely proposed but even if approved are eventually cut back and stretched out. |

In addition, within the space community, there exist severe splits between those who support unmanned or robotic missions as opposed to human spaceflight programs. These distinct clusters of space exploration supporters, especially the former, see the competition for scarce resources as essentially zero-sum; that is, if one wins, the other loses. Strategies to overcome this problem can take several forms, usually with bad results. One strategy taken by NASA when the space station program was originally set up after President Reagan’s approval of the program, over the objections of his science and political advisors, was to incorporate all the major NASA centers and other players into the program. The space station office originally was not located at any center in order to make the point that everyone had a piece of the pie, as it were. The result was a program out of control and incapable of disciplining itself to stay on schedule and within budget parameters. The result was a near-death experience in 1993 when the House of Representatives came within one vote of cancelling the program. That same summer, the Superconducting Super Collider program was cancelled due to a House vote. In addition, the cost overruns from the space station and the space shuttle forced the science community, including space sciences, to come out in public opposition to the station’s continuation since they saw its completion coming only at the cost of the space science community’s decimation. Given their previous history during shuttle development, they saw no alternative to becoming publicly critical of the space station. This was highly unusual within the Washington political community but reflected their desperation if Congress was not mobilized.

Moreover, for the public as a whole as well as much of Congress, the priority of the space program, especially its human spaceflight side, is low in comparison to other national priorities. When the public is asked to comparison shop between the space program and various social and defense programs, the space program loses and often badly. This has been a standard finding since the Apollo program when denunciations of a “moondoggle” were loudly proclaimed even as the Apollo 11 lifted off the launch pad. There was a civil rights demonstration at the gates of the Kennedy Space Center protesting the diversion of needed monies to a frivolous vanity program considered by some as similar to a potlatch ceremony among Northwestern Native Americans.

The ace in the hole for many supporters is the fact that one can cast the human spaceflight program as a pure and simple jobs program—who can be opposed to jobs for constituents? The mythology of the Apollo program neglects the crude reality that the program was seen by the Southern Democrats who dominated Congress in the 1960s as a source of constituent jobs and regional economic development. That linkage between NASA and its political patrons through the mechanism of jobs has been an important one for resisting change, or at least changes the agency did not want. The controversy over the current Obama program can be seen as a struggle for the soul of the future of US human spaceflight or, more crudely and equally accurately, as a fight over jobs, especially in Alabama (Marshall), Florida (Kennedy), and Texas (Johnson), the epicenter for the shuttle program and its successor Constellation.

This same job linkage occurred in 1972 with the shuttle approval decision by Nixon and in 1996 with Clinton’s approval of the X-33. In both instances, the focal point was specifically jobs in California in a presidential election year. However, other regions see job growth in expanding science missions, such the Jet Propulsion Lab (JPL) in California and Goddard in Maryland. So, even among congressional supporters, there exist differences depending upon what benefit they see as coming to their area and their constituents. Constituent jobs is a both a political virtue and a vice depending on which way the current is flowing. When budget times are normal, all sides agree to go along but when crisis arises, it is every senator and representative for himself.

| What has long protected NASA and the exploration program from outside competition in the form of the private sector has been the continued inability of the private sector to match its hype with its actual performance. |

Even more damning for NASA is the reality that it is remains a government agency, with all the stigma that incurs in American political culture. The private sector is clearly perceived as more compatible with American values. One must remember that efforts to privatize or commercialize the space shuttle date back to Carter Administration, even before the shuttle flew its first mission. The Reagan Administration also had such designs on the shuttle but those floundered on the shuttle’s flight problems even before Challenger in 1986. The shuttle was to be the equivalent to a bus with a regular and relatively fixed schedule. Launch delays and safety concerns made the shuttle a non-starter as a commercial vehicle once the subsidies were withdrawn. Gingrich and Walker also argue the point that the commercial or private sector should be the path forward in their Washington Times op-ed. “Reliance on commercial launch services will provide many other benefits. It will open the doors to more people having the opportunity to go to space. It has the potential of creating thousands of new jobs, largely the kind of high-tech work to which our nation should aspire. In the same way the railroads opened the American West, commercial access can open vast new opportunities in space. All of this new activity will expand the space enterprise, and in doing so, will improve the economic competitiveness of our country.” The difficulty has been that the space shuttle never was capable of becoming the space equivalent of a railroad both in terms of schedule and steadily falling costs.

What has long protected NASA and the exploration program from outside competition in the form of the private sector has been the continued inability of the private sector to match its hype with its actual performance. As mentioned above, the private sector argues for freedom from government interference and restrictions imposed by outdated policies. Many of those policies, such as those that hindered development of a robust remote sensing industry, have been removed, but the area of the most disappointment remains space launch, where private ventures have a checkered past. For many years, the complaint was unfair competition from the space shuttle with its subsidized payloads. That problem went away after Challenger exploded during liftoff in 1986. The next complaint was unfair competition from international competitors such as Russia (after the fall of the Soviet Union) and China—those competitive threats were limited by a series of agreements setting constraints on pricing and number of payloads the two could launch.

More damaging was the failure of the comsat boom of the early and mid 1990s to come to fruition; instead, Arianespace, plus some tamed international competitors such as International Launch Systems and Sea Launch, dominated the market. The failure of NASA’s X-33 program killed the RLV effort while the military’s EELV program upgraded the standard US launch vehicles, the Delta and Atlas. Both those programs occurred because the federal government funded them at least initially. The current SpaceX Falcon 9 and the Orbital Sciences Taurus 2 are being developed to resupply the ISS but one must note though that both programs are being supported by NASA contracts, which make protestations of pushing forward regardless of the risk somewhat difficult to credit. This continued dependence at least partially undermines the private sector’s claims that it is ready to step up as the shuttle’s replacement (see “Will NASA’s embrace kill NewSpace?”, The Space Review, February 15, 2010). However, NASA’s continued problems with developing a shuttle replacement continue to lend credence to a private sector approach.