Prognosticating NASA’s futureSurveying the road ahead between hopeful change and future’s endby Bob Mahoney

|

| As the most strident supporters and critics would have it, the US space program is either on its way to finally opening up the solar system to high adventure and commerce, or it’s being abandoned completely. |

At face value, portions of this approach make a lot of sense for moving our nation forward in space. Encouraging private industry to come up with new LEO access options and NASA’s investing in high-leverage technologies that will open avenues for deep space exploration and exploitation have both been advocated for years from various quarters. I must confess, however, that I harbor some lingering doubts.

Call me suspicious, but is it not strange that an administration who for more than a year has insisted that a government-provided option in healthcare is necessary for introducing competition and reducing costs now suggests that the best means of fostering competition in the LEO access industry is to eliminate the already-in-work government option that holds a 50-year pedigree?

As for the exploration end of the roadmap, it seems so… aimless. I have always been a firm believer in the wisdom of exploiting the relatively close lunar surface as a staging base for opening up the entire solar system, not just getting people on Mars:

- for gaining experience (akin to how Gemini contributed to Apollo’s success);

- for supporting logistics (establishing stable infrastructure outside Earth’s deep gravity well in a not-unfamiliar environment);

- for tapping resources (accessing material already outside Earth’s deep gravity well—including the recently confirmed water ice).

Consequently, removing investigatory lunar surface operations from the first tier of a beyond Earth orbit (BEO) architecture strikes me as ill-advised, since having it first on the list could very well make getting everywhere else (including Mars) substantially easier. (This premise was the original backbone of the 2004 Vision for Space Exploration.)

Admittedly, the Obama approach does not explicitly exclude such lunar operations further down the road. But what of the other redirections in policy? Is US human spaceflight on the cusp of pouring concrete for a superhighway to a brilliant future, or is this policy (introduced curiously not in an inspirational bit of oratory but merely through a budget submission that seemingly caught even NASA Public Affairs offguard) paving a footpath to a dark grave? Can any of us predict what’s ahead for the United States on the road to the final frontier?

Crystal balling

One can predict the future to a certain extent, as long as the prediction:

- is based on reasonable and accurate supporting data;

- doesn’t reach too far ahead; and

- comes with some sort of probability (or at least a grain of salt) attached.

No, I’m not talking about psychic visions; more like political/technical/commercial extrapolation into the realm of the probable. People individually and collectively often act in predictable ways. Also, physics and chemistry necessarily constrain technology even as economic and societal factors frequently channel its application down anticipated paths. Some circumstances and developments will always come flying at us from left field, but in matters of technology, commerce, and human behavior, certain outcomes often stand out as more likely than others if one assesses present circumstances carefully.

Consider a curious example from another era: Morgan Robertson’s novella Futility, published in 1898, imagined a huge, opulent British ocean liner named the Titan racing across the Atlantic toward New York during April, hitting an iceberg on her starboard side near midnight, and sinking with massive loss of life. Only 14 years later, down went the Titanic. Some aspects of this fictional story were amazingly aligned with what came true while others were not. Psychic premonition? Hardly. The international race for the Blue Riband was well-known during the period [1], so imagining such a scenario really wasn’t all that remarkable a feat. (As for the similarity in the ship’s name, well, there are only so many synonyms for “large” befitting a ship.)

| The key to accurate forecasting lies in choosing one’s foundational assumptions carefully, something akin to the GIGO principle: Garbage in, garbage out. |

I myself pulled off something similar (if not so exact) a few years ago. As I was converging on the final draft of my novel about a space shuttle trapped in orbit due to port-side thermal protection damage from a debris impact, the Columbia tragedy occurred. Suddenly, much of what I had already written became what-if discussion fodder on the evening news and later, operational protocol: rescue scenarios, lifeboat procedures, tile repair kits, etc. Again, no clairvoyance involved: Damaging the fragile TPS with external debris had come to me years earlier as the most plausible fit for my desired storyline because it was an actual technical possibility in the face of a genuine spaceflight hazard.

In fact, science fiction authors have been predicting future developments and sometimes even nailing details for more than a century. Recall Jules Verne’s moon-bound Columbiad launched from Florida. But, of course, sometimes they don’t get everything right: Verne launched that same mission with a cannon! Even Kubrick and Clarke, amazingly precise with operational details in 1968’s 2001: A Space Odyssey [2] missed with their larger vista of commercial spaceliners commuting to massive lunar bases (at least with their timing—some of us are still holding out hope!).

The key to accurate forecasting lies in choosing one’s foundational assumptions carefully, something akin to the GIGO principle: Garbage in, garbage out. But while authors of fiction may sometimes get lucky, would anyone be able to successfully forecast government policy and its consequences?

Perhaps. While humility should keep me from saying, “I told you so,” in the matter of the current space policy, I actually can: I predicted the essentials of this new Obama space policy even before the President won his party’s nomination! Here’s an excerpt from an e-mail to a friend dated February 22, 2008 (restated since on a few blogs out there):

If a Democrat is elected, everything beyond earth orbit will get turned back into “advanced studies” and ISS ops will be continued indefinitely using a simplified Orion.

First, note the accuracy of this prognostication as it compares to the proposed policy: “everything” beyond Earth orbit essentially is being turned into “advanced studies” (versus a metal-cutting operational program); ISS operations are to continue “indefinitely” (=beyond the originally proposed 2016 wrap-up of US participation); and a “simplified Orion” (=smaller ISS taxi vehicle) is to be pursued.

But note too where I missed—incorrect predictions can sometimes be just as instructive as correct ones: the lack of a precise ISS operations termination date (minor miss), the “advanced studies” are to include real demonstration missions (medium miss), and the “simpler” LEO access is not to be a traditional NASA-run program (major miss). Note too that I never mentioned Ares 1; to be honest, I just wasn’t sure if the “simplified Orion” would be moved to an EELV or not.

How’d I get anywhere close? I traced a line from the Carter administration’s space policy through that of the Clinton administration into the then-current circumstances. The former explicitly stated that no new Apollo-like exploration efforts would be undertaken so as to focus NASA on space shuttle development, while the latter retreated from the previous Republican administration’s Space Exploration Initiative to focus on ISS operations in a scaled-back (Freedom to Option-A to ISS) space station design. Given the then-current lay of the land that was Shuttle, ISS, and Constellation (another Republican administration’s product), my prediction was safely “in character” for a post-Vietnam Democratic administration. What caught me by surprise, since it was so obviously “out of character” (see “healthcare”, above), was the LEO commercial competition angle.

So, one can sometimes predict the future with some accuracy, even in matters of space policy. But what of the fallout? Is there any chance we can accurately forecast where this new policy might actually lead the country? Is it, as fans and detractors are respectively painting it, Ferdinand and Isabella’s backing of Columbus or, instead, the Ming Dynasty’s burning of their fleet?

How to constrain a WAG

Instead of attempting a single potshot crystal ball prediction for the whole shebang, it may be more instructive to paint the boundaries of possible future outcomes stemming from the individual elements of the policy, employing our knowledge of technology, politics, and human nature as our brush and palette. Hopefully, if we cast our limiting scenarios carefully, we’ll have a good shot at catching the true future somewhere in-between.

This approach is similar to a tool of paleontology termed extant phylogenetic bracketing. If two related extant types of organisms (say, birds and crocodiles) each possess a certain physical attribute (sinus structures) not normally preserved in the fossil record, then any extinct organism type (dinosaurs) that lies inbetween on their family tree will also very likely possess that same physical attribute [3]. Well-fitting analogy or not (it extrapolates backward instead of forward, after all), it’s a cool term and concept, isn’t it?

What I offer below are some reasonable “potential outcome” brackets for the four main elements of the new space policy: cancelling Constellation, extending ISS operations, the commercial LEO access competition, and the technology development effort. While the four matters are obviously intertwined, exploring their separate potentialities and then considering how they might possibly interact will likely offer our best chance to predict the future—within bounds, of course—and perhaps even suggest possible motives behind the new policy that aren’t necessarily apparent on the surface.

Ding, dong, the Stick is dead—or is it?

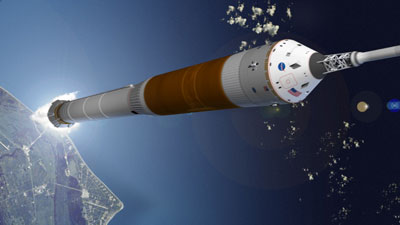

By almost all accounts (certainly if all the acrid commentary out in the blogosphere is any indication), the Constellation program, former NASA administrator Michael Griffin’s “Apollo on Steroids” technical response to the Bush VSE policy roadmap, was in serious trouble both financially and technically. To all appearances, the agency’s decision to attempt development of two new (but partly shuttle-derived) boosters under the Ares program (not an envisioned component of the original VSE) while it also created the Orion crew ferry and Altair lunar lander spacecraft—nearly all components being one-mission-only disposable—resulted in a budget-bending, schedule-slipping, four-year slog whose only avenue for success became, as to the Augustine Committee’s assessment could be paraphrased: “Send more money. A lot more money.”

| Constellation became a budget-bending, schedule-slipping, four-year slog whose only avenue for success became, as to the Augustine Committee’s assessment could be paraphrased: “Send more money. A lot more money.” |

As set forth, the new Obama policy will drive a big stick (sorry) through the Constellation program’s heart. Or will it? Rumblings on Capitol Hill and actions inside NASA already suggest that Constellation may very well be a reluctant corpse. As in all these matters, Congress will play a significant role because they control the purse strings. And even entities within NASA retain some influential capacities of their own.

So what are the most obvious boundary scenarios here? “Worst” and “best” case (depending on your views) would be either complete cancellation as defined in the budget submission, or Congress balks and restores full funding to all Constellation components, perhaps even adding the billions supposedly needed to make it work.

But those boundary scenarios obviously don’t help us much. For the former, the likelihood of Congress rolling over completely is slim, and for the latter, Constellation’s mounting budget and schedule troubles can’t be ignored, and such a move would be a slap in the face to the President. Members of Congress are bound to do something though because, well, that’s what Congress does: it’s part of their nature to either allocate funds or impose restrictions. (Sometimes, as we all know, the best thing to do is nothing, but persons elected to Congress always seem to forget this.)

To bracket possible outcomes for Constellation’s proposed demise I’ll divide the program into its two primary components, spacecraft and launch vehicles. Recall the original planned spacecraft roster for Constellation:

- Orion, to serve both as a LEO taxi and as the command-module-like crew quarters for trips to and from lunar orbit (and, theoretically, beyond);

- Altair, the separately launched lunar lander that would (as originally envisioned) ferry all four lunar crew to and from the lunar surface to support both any-desired-location sorties and buildup of an outpost at the south lunar pole.

Thus far, Orion had already grown beyond its booster’s ability to lift it, until the program began to unceremoniously jettison its broader features: land landing, six-person ISS taxi crew, etc. Meanwhile, the pregnant-fire-hydrant-like Altair had already been zeroed out of the budget to await funds to be allocated down the road.

For Constellation spacecraft bounding scenarios, I offer the following:

|

(A1) NASA will be directed to downscale Orion into a LEO-only version that can be launched on industry-provided (i.e., EELV-caliber) rockets. All of its BEO capabilities will be stripped. Operations will continue under the guidance of NASA Mission Control in Houston as JSC studies the possibility of handing off such operations to a prime contractor. Altair per se stays out of the budget even as low-key studies of possible lander configurations continue in-house. |

(B1) While LEO duties are handed over to industry (but see below), NASA will be directed to focus immediately on real (versus paper-only) development of a deep-space version of Orion (perhaps not under that name) whose configuration does not rule out support of lunar landing operations via another Altair-like spacecraft even if, on the outside, its primary motif is “look-but-don’t-touch” asteroid/lunar/Mars fly-bys. Like in (A1), operations, when they begin, will remain under the purview of NASA. |

Note the aspect common across both these bounding scenarios: NASA will continue to develop its own spacecraft controlled by its own organization and (not incidentally) flown by its own astronauts. If there’s one lesson history has taught us about government programs and agencies, while projects may come and go or even be cancelled mid-stream (like Apollo), institutions, once established, remain amazingly resilient. While Apollo the program was cancelled 40 years ago, the institutions of Apollo (JSC, MSFC, KSC, etc.) are still with us today supporting shuttle, ISS, and Constellation, even if their internal workings, or at least the organizational labels, have been shuffled dozens of times.

| At the very least, I would expect NASA to still (or relatively soon) be flying a crewed spacecraft of its own—to somewhere—after shuttle retires, regardless of the name it carries. |

Consider: the cost-saving suggestion to close any of NASA’s ten field centers has been taboo for decades since Congress must bring home the bacon: that’s just the way things work. The paradigm of NASA Mission Control directing NASA missions piloted by NASA astronauts goes much, much deeper than mere pork-barrel politics; it has been woven into our nation’s DNA. Merely staffing the space station for another decade won’t suffice to satisfy that expectation, especially if our astronauts must catch rides on another nation’s rockets for any length of time. The premise of NASA losing its birthright role in US human spaceflight, even for LEO access, seems most unlikely—certainly not until the agency has something real of its own to fly coming unmistakably down the pipeline. This is the major difference between the upcoming “spaceflight gap” and previous ones: earlier periods of no US human access to space were accompanied by ongoing metal-cutting development of the follow-on spacecraft or the return to flight of the current one.

At the very least, I would expect NASA to still (or relatively soon) be flying a crewed spacecraft of its own—to somewhere—after shuttle retires, regardless of the name it carries. Whether or not that spacecraft flies on a NASA booster is another matter.

Sticks and stones may break our budgets

For Constellation’s launch vehicle question, recall the program’s intended stable of rockets: Ares 1 to launch Orion into LEO to support ISS and the Earth-orbit rendezvous (EOR) of later lunar missions, and Ares 5 to launch the Altair lunar lander (unmanned) and Earth Departure Stage to this EOR before the joined spacecraft went to the Moon. In the grander scheme of things, Ares 1 was to serve as investment in Ares 5 development since both would employ SRBs and the J-2X hydrogen/oxygen upper-stage engine.

I believe the following boundary scenarios are most reasonable for the future of the Ares program (or at least its supporting personnel):

|

(A2) Ares 1 remains cancelled as human LEO access moves to EELVs or other industry-provided boosters. Ares 1/5 work gets redirected in pieces parts to support development of: (A2.i) some nebulous future advanced NASA heavy-lift launch vehicle (HLLV), first launch date uncertain or (A2.ii) a NASA side-mount HLLV (4-segment SRBs) configuration in parallel with stretching shuttle flights out until the LEO spacecraft can fly on an EELV or equivalent booster. |

(B2) NASA continues development of Ares 1 as a “guaranteed back-up” until at least one of the Merchant Seven (or another) achieves a successful rendezvous and link-up with ISS with a spacecraft (private or NASA) capable of carrying crew. While an Ares 1 may never fly an operational mission, its continuing development could feed—in some capacity and with a sizable gap in operations—into a currently undefined follow-on heavy-lift launch vehicle that bears some similarities to Ares 5, first launch date unspecified. |

Given that NASA has flown its spacecraft atop another’s boosters before (Mercury and Gemini), the first scenario (A2) strikes me as a reasonably likely means of eliminating the most troublesome component (thus far) of the Constellation architecture even as NASA keeps its core human spaceflight institutions occupied by flying their astronauts on EELVs (or some other industry-provided booster). Given that the new policy specifically mentions pursuit of new HLLV technologies, it only makes sense that NASA (with Congressional help) would try to make lemonade for the sake of its workforce by directing its Ares people toward any remaining “in-house” heavy-lift booster effort.

As for (A2ii), a side-mount design of some sort has the advantage of minimizing the impact to KSC ground interfaces and processes and would thus lessen transformative overhead, even more so than the imagined DIRECT architecture with its in-line configuration. But this only carries substantial viability if we’re going to keep said interfaces around for something else, namely more shuttle flights to close the gap. But extending shuttle, even at a significantly reduced flight rate, would be a seriously challenging (i.e., costly) premise because of component production line shutdowns and already-completed pad modifications. As many have indicated, shuttle shutdown by 2011 is very likely a ship that has already sailed.

For (B2), Ares 1 and Ares 5 are intertwined not unlike the way a side-mount HLLV and sustained shuttle operations would be. It makes little sense to pursue one unless the other is part of the package. And since NASA can’t seem to shake the mindset that it absolutely, positively, needs an HLLV sometime in its future, and a number of influential folks in Congress remain enamored of the Constellation architecture, an Ares 1/5 specter of some sort may persist in one form or another to haunt (or sweeten) the dreams of future NASA administrators.

While I am reasonably confident the future of Constellation (whether or not any program pieces retain that name) will fall somewhere in-between these boundaries (I’d bet my money on it lying closer to (A1) & (A2.i)), the outcome of the 2010 mid-term elections will likely be a very important, if not the dominant, factor in deciding Constellation’s actual fate, and the fate of the other space policy elements as well. Remember, we’re talking about Congress. They can’t help but do something.