Tough little spinnerby Dwayne A. Day

|

| There was a time when comsats were much more distinctive, large rotating drums wearing an ostentatious antenna display at their top like a fancy woman’s hat. |

One of the steps along the way was a series of four satellites produced by the company in the latter 1970s and known as Comstar. Two of the Comstar satellites had incredibly long lives. One of these may still be operational, although it certainly does not provide communications services and may be primarily a squatter, sitting on an orbital slot so that its owner does not lose the slot to a company that also wants to use it.

When commercial communications satellites first started operating in the 1960s, their primary role was serving as links across the oceans. Laying undersea cables to carry telephone and television transmissions was—and remains—costly. And at the time there was a limit to how much information could be crammed through copper cables. Satellites offered an economical alternative to laying cable, and so the first comsats were pressed into service over the Atlantic Ocean. Later comsats were also used for relaying television signals over the United States and Europe.

By the 1970s the telecommunications industry had evolved to the point where it became economical to use satellites for relaying telephone communications within the domestic United States. Comsat General Corporation hired Hughes Space and Communications Company (now Boeing Satellite Systems) to build four spin-stabilized satellites for telephone communications. Comsat in turn leased the satellites to American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) and a subsidiary of General Telephone and Electronics. The satellites were named Comstar.

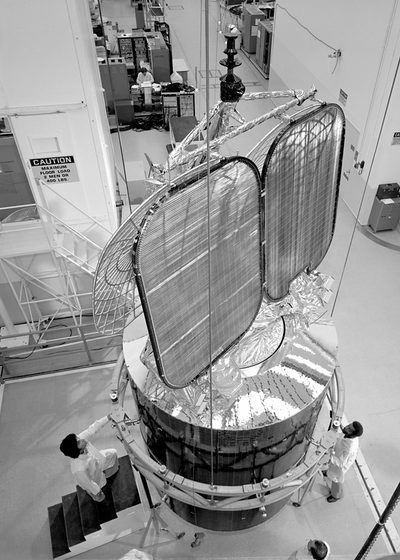

A Comstar 1 satellite being assembled. (credit: Hughes) |

Polarized in two directions

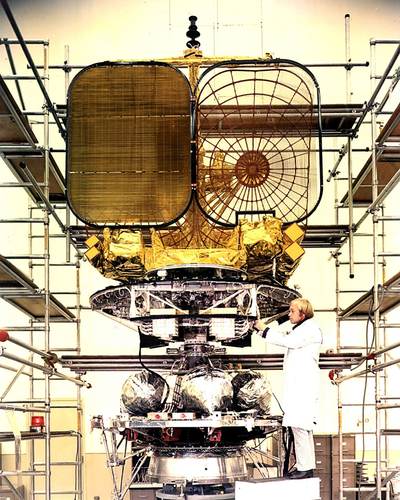

The Comstars used a unique trick to increase the satellites’ communications capabilities. This trick is readily visible in photographs of the satellites’ antennas. Ground stations transmitted up to the satellites on 6 GHz frequencies and the satellites transmitted to the ground on 4 GHz frequencies. They operated in the C-band frequency.

Earlier Hughes-built communications satellites had carried only twelve transponders. Hughes engineers doubled the number of transponders on the satellites to twenty-four, but used a signal polarization technique that enabled each satellite to use each frequency twice without interference. They did this by polarizing one antenna vertically, and the other horizontally. As a result, the transponders were capable of relaying a total of more than 18,000 telephone calls simultaneously. Photos of the satellite show two large antennas—one with a vertical screen, the other with a horizontal one.

In addition to the C-band system, the satellites also carried a millimeter wave experimental package for communicating in the 19 and 28 GHz bands. At the time, Hughes expected that communications satellites would soon begin operating in higher-frequency bands, now known as Ku- and Ka-bands.

Each Comstar had a height of 20 feet, 9 inches (6.34 meters) and a diameter of 7 feet 9 inches (2.38 meters), with a liftoff mass of 3,348 pounds (1,516 kilograms). They were covered with 17,000 solar cells providing primary power of 760 watts.

In the 1970s there was no commercial launch industry in the United States. NASA launched all civilian and commercial American satellites, hiring contractors to build and launch the actual rockets. Comstar contracted NASA to launch four satellites atop Atlas-Centaur rockets.

| An outside observer would conclude that the satellite, which probably has only minimal capability at best, is currently being used to squat on a valuable piece of orbital real estate until Tongasat can find a company willing to pay for that slot. |

The first Comstar was launched on May 13, 1976, and began commercial service in early July. Known as Comstar 1A, the satellite operated for eight and a half years. The second satellite, known as Comstar 1B, was launched on July 22, 1976, and was located at 76.6 degrees west longitude. It eventually operated for seventeen years. The third satellite, Comstar 1C, launched on June 29, 1978 and began operations in August. Like Comstar 1A, it operated for eight and a half years.

The final Comstar was launched on February 21, 1981, and placed at 75.4 degrees west longitude. In 2001, twenty years after it was launched, SSC Parallax purchased the satellite from LMGT and renamed it Parallax 1. In April 2002, Parallax sold the satellite to Tongasat, although Tongasat claims that it purchased the satellite from Seattle Scientific Corporation. It was renamed Esiafi 1.

A Comstar 1 satellite being assembled. (credit: Hughes) |

Tongasat: a polarizing company

Tongasat is somewhat infamous within the comsat community. The Kingdom of Tonga is an archipelago in the South Pacific Ocean consisting of 169 islands located east of Australia and New Zealand. In the late 1980s an American businessman approached the kingdom with a plan. Because of its location, Tonga was entitled by international agreements to some of the geostationary orbital slots overhead. But in order to lay claim to them, the country needed to demonstrate that it could use them.

So an American businessman and a member of Tongan royalty, Princess Pilolevu, formed a business with another American businessman and King Tupou IV. The company was named Friendly Islands Satellite Communications Inc. and does business as Tongasat. The first American businessman loaned the company the startup funds. The Tongan government contributed no money. Shortly before Tupou’s death, he gave his shares to the Princess; she now holds a 60 percent interest in Tongasat.

Tongasat laid claim to sixteen orbital slots. This was a bold move, because until that time companies only requested orbital slots that they were actually going to use themselves. Tongasat had no satellites and no capital to purchase or rent satellites to operate in its orbital slots. Eventually Tongasat reduced its request to six slots, which were awarded in 1991, with a seventh added a year later. The slots are in prime locations, enabling satellites to connect the United States with Asia. Over the next several years, Tongasat signed up customers who rented the slots for their satellites. But the company’s business has been controversial, as one would expect when members of royalty establish a company that they directly benefit from.

Today Tongasat’s website lists Esiafi 1—the old Comstar 1D—as its only space asset, although it mentions nothing of the satellite’s health or capabilities, or its origins as an American comsat three decades ago. Esiafi 1 is supposedly located at 70 degrees east, and the company claims to be “able to offer capacity on ESIAFI-1 on a highly competitive basis,” although this seems highly dubious.

An outside observer would conclude that the satellite, which probably has only minimal capability at best, is currently being used to squat on a valuable piece of orbital real estate until Tongasat can find a company willing to pay for that slot. Whether it is dead or alive, the ancient spinner is still rotating silently in its prized orbital position.