Debating a code of conduct for spaceby Jeff Foust

|

| DeSutter is concerned about one passage in the Code that could be a first step to space arms control. “It sort of ties you to something you may or may not want to do, and probably in my view shouldn’t do.” |

One thing the document does not do, that many observers in the days and weeks leading up to its release thought it might, is formally endorse a “Code of Conduct” for outer space activities promulgated by the European Union. That prospect attracted enough attention—and, in some quarters, concern—that nearly 40 members of the Senate wrote to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton last month, asking her to consult with the Senate before signing on to the EU Code (see “Six answers to 37 senators”, The Space Review, this issue). But as many inside and outside government have recently noted, that it’s far too early for the US or anyone else to sign onto a code that is still very much a draft.

Critiquing the Code

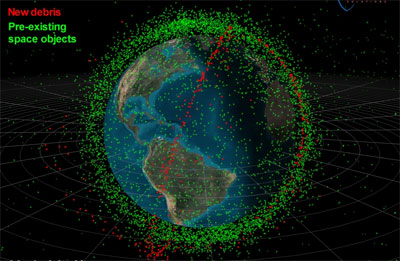

The draft “Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities” was first published by the EU in 2008, with a revised draft released last September. The document calls upon countries to refrain from actions that would damage or destroy other satellites or interfere with their communications, and to minimize the risk of collisions, as well as limit the creation of orbital debris, among other measures. “[T]he formation of a set of best practices aimed at ensuring security in outer space could become a useful complement to international space law,” the Code’s preamble states.

In many respects, the Code’s provisions are hardly controversial, and reflect commonsense practices for operating in orbit. “If one reads it, and reads it in the context of the US National Space Policy, you come away with a large sense of agreement on basic principles,” said Jeff Kueter, president of the Marshall Institute, said in the introduction to a panel session hosted by his organization last month about the EU Code. Both documents are full of “motherhood and apple pie statements”, he said: passages that are widely accepted and noncontroversial.

Some, though, take issue with specific provisions in the Code. Paula DeSutter, former Assistant Secretary of State for Verification, Compliance, and Implementation, took issue at the Marshall Institute forum with Section 4.5, which calls for “further security guarantees within the appropriate fora for the purposes of enhancing the security of outer space activities by all States and the prevention of an arms race in outer space.” That passage, she said, is a “slippery slope” towards broader arms control in space that should be stricken from the document. “It sort of ties you to something you may or may not want to do, and probably in my view shouldn’t do,” she said.

DeSutter is also concerned with Section 5, which calls on signatories to “refrain from the intentional destruction of any on-orbit space object or other activities which may generate long-lived space debris”. “On its own, it’s not good,” she said, since it doesn’t include any exceptions for cases like self defense. However, she noted those caveats are found elsewhere in the document, so it would be simple to incorporate similar provisions in that section.

Scott Pace, Director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University, noted at the Marshall event that Section 2 of the EU Code refers to “international law and security, safety and integrity standards” for respecting the safety of objects in space, without being more specific. “I always worry about whose standards, and what are those requirements, and what do they mean,” he said.

| “I would say the US should never sign an EU Code of Conduct,” said Pace, beliving that other nations should be consulted with first. |

Peter Marquez, the former director of space policy at the National Security Council who helped craft the current National Space Policy, brought up on the panel a passage in Section 6.1 of the Code that requires notification when spacecraft perform maneuvers in “dangerous proximity” of other objects. “‘Dangerous proximity’ all depends on one’s inherent capabilities,” he said. Some, like ISS partner nations, can safely operate very close to the space station. “Another nation that has no idea what they’re doing gets within one kilometer of my satellite, and I’m going to be scared.”

He was also skeptical about the utility of Section 9, which provides a “consultation mechanism” and means to “investigate proven incidents” in space, leaving the specific details of such investigations for later. “That one just seems to be, in some ways, ripe for theater,” he said. “I can just see this going the wrong way, that it just becomes an investigation after investigation of the US.”

While critiquing various details about the EU Code, the panelists were all generally supportive of the general aim of the document, particularly when compared with a more restrictive proposed space arms control treaty, known by the acronym PPWT, supported by China and Russia. “I think the EU has done a good job,” DeSutter said. “I think it is not something that should be rejected out of hand.”

Enacting the Code

While the general aims of the EU Code may have broad support, that doesn’t mean the US is likely to formally sign onto the document—in part because the document itself remains a draft that may be years away from being formalized.

“Even if the administration decides that it wants to sign the EU Code, I think it would be a significant mistake for it do so anytime soon,” DeSutter said. Instead, she said the US should wait until it’s clear that the document is in its final form, with no additional significant changes planned, before signing on. In the interim the administration could issue a statement supporting the Code while working to finalize the document’s text before signing. “Our leverage to make sure that this is an okay agreement ends the moment the United States puts its signature on it.”

“I would say the US should never sign an EU Code of Conduct,” said Pace. Instead, the US should be consulting with a wide range of countries, including emerging space powers in Latin America, Asia, and Africa, to get their buy-in to the document. “For a code of conduct to really be useful, it needs to represent an emerging international consensus.”

| “We are looking with great interest at this code of conduct and working with the Europeans,” said Deputy Secretary of Defense Lynn. |

Even if the US was to sign on some version of the EU Code, both DeSutter and Pace believe it would desirable, if not necessary, to get the approval of the US Senate. DeSutter said it wasn’t clear if Senate “advise and consent” was strictly required for a document with less standing than a treaty, but that it would still be useful. “For me, it doesn’t matter if it’s required,” she said. “My general approach is, on something that is very significant, like this, for national security, go ahead and seek advise and consent. Go ahead and put it through those tests.”

A benefit of getting Senate support for the document is that it would make it clear to other countries that the US backed it. Other countries “look to see if the two ends [of Pennsylvania Avenue] are in sync,” Pace said. “And where they are in sync, in things like remote sensing and GPS, they know there’s policy stability and they can rely on it.”

It may take some time before there is a version of the Code of Conduct ready for the Senate to formally consider. “Basically, this document is more like an internal memo for us,” said László Deák, political counselor with the EU’s delegation in Washington, referring to the current draft of the EU Code. “This is not intended to be an international legal document. Debating the merits of the document is very important, but at the same time, we are just inviting you to talk about it. We are not inviting you to sign on to it.”

In that respect, then, it’s not surprising that the new National Security Space Strategy doesn’t explicitly mention the EU Code, even though some of its provisions, such as “promoting responsible, peaceful, and safe use of space” are broadly consistent with the goals of the EU document. Late last year administration officials noted that consistency while suggesting that a US decision on supporting the EU Code would come in the near future (see “Securing space security”, The Space Review, December 20, 2010).

At a forum on the new space strategy convened last month by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Deputy Secretary of Defense William J. Lynn III confirmed continued US interest in the EU Code, without explicitly endorsing the current draft. “We think it promotes transparency and responsible use of space. So we think it’s a positive. It has a very strong potential of being a positive step,” he said. He added that he expected a “final” draft of the code from the EU in the next 12–18 months. “We are looking with great interest at this code of conduct and working with the Europeans.”

Given that the EU Code carries less standing than a treaty, and lacks any effective enforcement mechanisms, just what benefit does it provide? Pace suggested at the Marshall event that its strength is in dealing with new spacefaring nations rather than established powers like Europe, Russia, and China. “I am concerned about some of the new entrants, some of the new drivers on the road,” he said, who launch satellites with little means of tracking them to ensure they don’t pose a hazard to themselves or other spacecraft. “They don’t really necessarily know where these things are and what they’re doing and where’s they’re going.”

Having a code of conduct in place, he said, provides a means for consultations with and education of these nations without the appearance of being overbearing. Having the US wanting to talk with a country “about how you can do a better job of running your space program” doesn’t always go over so well, he said, but doing so within the context of an international code of conduct can be more constructive. “Could you do it without it? Yes, you could, but it’s more difficult.”