Opening GAMBIT: The development of the KH-7 reconnaissance satelliteby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Although presumably many more details about GAMBIT—possibly including an engineering test model of the KH-7 satellite—will emerge in a few months, it is already possible to add to what is already known about this program. |

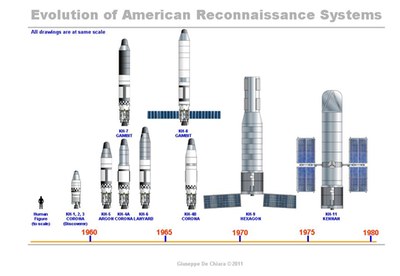

The KH-9 HEXAGON was a big satellite that took medium-resolution photos (on the order of 0.5 meters or better) of massive amounts of territory. Twenty satellites were launched between 1971 and 1986, although the last one blew up above its launch pad (see “The Flight of the Big Bird”, The Space Review, March 28, 2011). GAMBIT was a high-resolution satellite that took photos that ultimately were capable of showing an object as small as a baseball on the ground. The first KH-7 GAMBIT satellite launched in 1963. It was replaced by the KH-8 version later in the decade. Over 90 of the satellites were launched until 1984. Both the HEXAGON and GAMBIT satellites used film that returned to Earth in reentry capsules. The government declassified KH-7 imagery and the KH-9’s mapping camera imagery in 2002.

The broad outlines of the GAMBIT program are known (see “Ike’s gambit: The development and operations of the KH-7 and KH-8 spy satellites”, The Space Review, January 5, 2009). Although most technical and programmatic details of these two satellite programs remain classified, the NRO released portions of official program histories over two years ago. They contain a significant amount of information on the programs. Although presumably many more details about GAMBIT—possibly including an engineering test model of the KH-7 satellite—will emerge in a few months, it is already possible to add to what is already known about this program.

GAMBIT was first proposed around the time that Gary Powers was shot down in his U-2 spyplane over the Soviet Union in May 1960. When GAMBIT was first conceived, the United States had no operational reconnaissance satellites, Samos E-1 and CORONA were experiencing failures, and four additional reconnaissance satellites (Samos, E-2, E-3, E-4, and E-5) were at some stage of development, but ultimately would never return useful photographs of the Soviet Union, either because they were canceled or because they failed.

Following the U-2 incident, various reconnaissance contractors proposed new systems to fill the gap caused by the loss of high-resolution imagery of the Soviet Union. Eastman Kodak had been advocating a new camera system for several months before the incident and it impressed senior intelligence advisors to President Dwight Eisenhower. The camera proposal beat out an alternative and far less-capable proposal from the Space Technology Laboratories (which eventually became major aerospace contractor TRW) and another proposal from experts at the Rand Corporation.

By summer 1960 Eisenhower had approved developing the new system. But no decisions had been made about a spacecraft to carry it. One important decision that the reconnaissance leadership made at that time was that the new program would be covert and managed by the Air Force. This was unprecedented, because the Air Force had no history of developing systems covertly, meaning that not even their existence could be publicly acknowledged. Senior officials developed numerous methods for concealing the existence of this new and expensive project. At least part of their strategy was to openly order equipment—like Atlas launch vehicles—without assigned payloads. Nobody looking at the procurement would think that a secret project would operate in the open.

The project apparently had a different code name at first, which was soon changed because it had been previously used. The new code name was GAMBIT. By November 1960 it apparently also acquired an unclassified nickname, although what it was remains unknown.

One of the big surprises in the newly released GAMBIT material was that the satellite was originally intended for land recovery. When the original proposal was made to President Eisenhower in August 1960, one of its major selling points was that the film would be recovered over land. The CORONA reconnaissance satellite, which took low-resolution images of large swaths of territory, was recovered at sea. After a string of failures it achieved its first success only days before Eisenhower approved GAMBIT. Apparently senior officials were becoming increasingly concerned that a CORONA capsule could land at sea and be retrieved by a Soviet ship or submarine. The U-2 incident, which resulted in the recovery of significant amounts of reconnaissance film by the Soviet Union, probably contributed to this worry. The GAMBIT reentry vehicle would have come down near Wendover Air Force Base in Utah.

| One of the big surprises in the newly released GAMBIT material was that the satellite was originally intended for land recovery. |

GAMBIT development progressed through 1961 and 1962. But there were problems, and the program slipped by about four months, moving the planned first launch from February 1963 to May 1963. The causes for the delays are unknown, but the designers had decided that the GAMBIT camera would be mounted on a spacecraft developed by General Electric. That spacecraft was complex in order to precisely point the camera and keep it stable while film moved through the camera system. However, the GE Orbital Control Vehicle (OCV) and the camera system would be pushed into orbit atop an Agena rocket that served as the second stage of the launch vehicle. The Agena was already serving as the spacecraft for the CORONA satellite.

Program manager Colonel Quentin Riepe proposed an expanded test program, involving more qualification tests, construction of more spares for the engineering development program, inclusion of complete hot-firing tests, provision of complete back-up development of major elements of the command system, and addition of three reentry vehicles to the basic test program. But the Air Force general in charge of classified satellite programs, Robert Greer, became concerned about maintaining the schedule. He raised the possibility of using the Agena in orbit to point the camera rather than dropping it after achieving orbit. This would produce lower quality photographs, but could allow them to maintain their schedule. Ultimately, Greer decided to accept the schedule slip.

Over time, Greer became convinced that the land recovery requirement was overrated. He believed that there was little danger of a Soviet trawler or submarine recovering an American reconnaissance satellite capsule and that the American recovery forces had already planned for this contingency. In addition, the large expense of maintaining a sea recovery force to back up air catch operations had been an issue in summer 1960, but the need for surface forces had disappeared by 1962.

The bigger problem was land recovery itself. According to the official history of the program, “In a descent toward the sea, a CORONA reentry vehicle could safely shed all sorts of accessories—hatch covers and the ablative cone being the most obvious. Such jetsam fell into the ocean without danger to anything below, and then sank into the secure obscurity of a cluttered sea bottom. A land recovery vehicle could shed nothing that might come to earth as a lethal projectile or which, if discovered, might breach the security of the satellite reconnaissance effort.” In addition, a vehicle coming down to land in the United States would first fly over Canada. If something went wrong it could come down there. If it overshot, it could come down in Mexico. Either case could be politically embarrassing and could blow the program’s cover.

By summer 1962 Greer raised his concerns to the civilian head of the American reconnaissance program Joseph Charyk. Greer believed that it might be possible to modify the GAMBIT to accept a CORONA-type recovery capsule. Charyk ordered a “white paper” on the merits and shortcomings of land recovery. He also suggested a study of the feasibility of designing a capsule that could be retrieved in any of several different modes. Later he called for a study of simplifying GAMBIT to “possible alternative modes of operation” including sea recovery.

Several months of study indicated that relatively minor modification of the existing CORONA recovery vehicle would enable it to carry the larger GAMBIT film. In addition, eliminating land recovery would permit earlier testing with less risk, reduce requirements for orbit adjust, and in theory enhance the probability of recovering film by reducing an unknown.

The more they studied the problem, the more they concluded that land recovery was problematic. The land recovery capsule would be heavier and more complicated than the CORONA capsule. It would take longer to develop. And it might take many years to perfect. The overriding requirement for GAMBIT was to get it into service fast and ensure its reliability.

Ultimately, by fall 1962, Charyk agreed to switch to sea recovery for GAMBIT. In retrospect, this was a very late date for such a major decision—GAMBIT had been in development for two years, and would ultimately launch in less than a year. Somehow, the engineers managed to pull it off. GAMBIT used the CORONA recovery capsule and was successful.

| All in all, the GAMBIT was successful from its first mission, and returned data far faster than the earlier CORONA program. |

After some additional hitches, including a vehicle collapsing on the launch pad (see “Not a bang, but a whimper”, The Space Review, March 16, 2009), the first KH-7 GAMBIT was ready for launch at Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. Months before launch, program officials decided that during the first mission they would leave the Agena attached to the spacecraft for most of the flight as backup to the OCV. They also included a roll joint that would allow the forward part of the spacecraft to roll to the left and right of the Agena’s ground track. Normally the OCV would point the spacecraft, but the Agena and the roll joint were already proven, and including them provided additional insurance. General Electric’s engineers were probably not pleased at this decision and its implied lack of faith in their spacecraft. In addition, some may have seen it as an ominous sign—if there were alternatives to their spacecraft, someday somebody might decide that General Electric’s Orbital Control Vehicle was unnecessary.

The launch took place on July 12, 1963. Launch vehicle and payload engineers as well as program officials were all watching the launch from a blockhouse near the launch pad. When the countdown clock reached zero and the Atlas ignited the cameras and telemetry in the blockhouse went dead. Everybody feared that an explosion had occurred, but seconds later the signals resumed and they realized that the Atlas exhaust had knocked out an electrical connection.

The spacecraft reached orbit, but suffered other glitches. When excess propellants were dumped from the Agena, the reactive force caused the spacecraft to move, forcing the General Electric Orbital Control Vehicle to use up a lot of control gas to correct it. However, enough remained for stabilization.

Apparently the GAMBIT camera was also out of focus. The best resolution was about 3.5 feet (1.1 meters), with 5-foot (1.5-meter) resolution on several stretches of the exposed film, and average resolution was about 10 feet (3 meters). Despite the problems, the mission returned the best photographic imagery ever obtained from a reconnaissance satellite.

Control over the OCV was lost after seven orbits during the mission and the Agena provided backup flight control. This also apparently led to a decision to rely on the Agena again for the second flight. But all in all, the GAMBIT was successful from its first mission, and returned data far faster than the earlier CORONA program.

One of the unknown questions about GAMBIT is whether the NRO ever considered land recovery again. During the mid-1960s, the Air Force conducted several tests of the PRIME lifting body, firing it on ballistic trajectories to see how it handled high speeds. Both NASA and the Air Force were interested in manned lifting body spacecraft at this time, but was PRIME also connected to efforts to develop a way of bringing reconnaissance film down to a landing site within the United States, such as Edwards Air Force Base? Hopefully, when GAMBIT is finally revealed in a few months we will learn the answer.