Transition to commercial services for LEO transportationby John Michael Lounge and Mary Lynne Dittmar

|

| Mike’s idea was to “phase” the entire commercial program via a logical transition from NASA-owned hardware and services to missions that were executed entirely by commercial providers. |

In late May, Mike called me on the phone and wanted to meet. I had been talking regularly with Paul Hill, the Director of the Mission Operations Directorate at JSC, and had discussed some of the ideas generated in those meetings with Mike. Paul was spearheading an innovative re-architecture and evolution of MOD and had begun discussions with commercial space companies earlier in the spring. (More background may be found in the series about Mike published at www.marylynnedittmar.com). One concept explored in those exchanges involved a phased approach to the development of ops expertise among commercial entities, beginning with missions controlled from MCC in Houston but progressing with less and less NASA involvement to commercial control over time.

Mike’s idea was to “phase” the entire commercial program via a logical transition from NASA-owned hardware and services to missions that were executed entirely by commercial providers. His plan consisted of five phases that he forwarded shortly after we tagged up. I made some modifications regarding contract structure and ops integration and kicked it back. Emails and phone calls flew fast and furious as our opinions quickly diverged about Phase III, which was the true “transition phase” (see this table). At that point my strategic planning background took over and the paper morphed into a treatise on the nuts-and-bolts of how to go about actual procurement, systems engineering and integration, and ops integration; how to manage crew selection and training once “mixed” crews came into being (which we forecasted for Phases IV and V); and so on. Thankfully, Mike pulled back at one point and suggested a three-phase approach that dispensed with much of the detail—and the table. I gratefully agreed, and we refocused on addressing the policy and programmatic implications of our proposal. To that end, some of the points in the paper were re-vectored specifically to address some of the political debates then driving much of the national discussion.

A draft white paper was eventually distributed far and wide for comment. We were fortunate to get input from almost everyone we sent it to. What follows is the final document, far better for all of the thoughtful comments we received. Once it was re-distributed in this form, however, we chose not to publish it. The hope was that it would provide food for thought in the midst of intense political battles in the summer of 2010. Our intention was to help, not throw more fuel on the fire.

The decision to finally publish it now, with the original table—a year after we first began writing—has come about as a result of three things. First, after 15 months of struggle stemming back to February 1 of last year, some progress has been made but many issues that Mike and I were concerned with remain unresolved. Second, the paper itself began to surface in late 2010 with just my name on it. This was a source of amusement for Mike, but also some frustration. Early in January of this year he noted that he had several good ideas and inputs in 2010, and not one had seen the full light of day. I assured him I intended to remedy the situation and made several tongue-in-cheek comments about “not taking the heat alone”—also much to his amusement. Mike also commented that because the paper was now “dated”, it might be useful for people to know how it came about: what motivated it, why we had bothered to write it in the first place. I agreed.

| This phased transition approach may take several years longer to get to the final full commercial service model. However, the benefits of this approach outweigh the extra time and additional costs. |

Little did I suspect that I would fail to correct the situation before Mike had the opportunity to see it done. After a brief illness he died on March 1 of this year, leaving us—friends, family, colleagues, the entire community of people invested in Human Space Flight—far, far too soon. Shortly thereafter, with inputs from several colleagues who were so helpful during the writing process, I determined to keep my promise. Jeff Foust has kindly agreed to publish the paper, and so here it is.

It is my conviction—and I know, Mike’s—that whether or not the ideas here are adopted is less important than what they represent; an initial attempt to explore a workable transition between 50 years of achievement in human space flight created and shepherded by NASA and the next 50 years, which will hopefully benefit from the efforts and creativity of NASA together with those in an emerging commercial space industry. It was only a first step, but it represents that vision we shared as authors—one we hoped would lend support to the effort Mike once called, “Building the pyramids of our civilization.”

- Mary Lynne Dittmar, May, 2011

Introduction

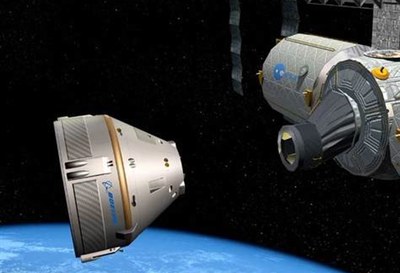

There is a good deal of skepticism within NASA and in the broader community about the ability of private companies to safely and reliably provide mission critical services such as crew transportation to the ISS, given their starting point today. There is also great pressure to take advantage of expertise and infrastructure from current NASA programs, representing as it does 50 years of investment, development, and especially the practice of human spaceflight. The stakeholders’ dialogue on this subject to date appears to assume that the move to commercial services for crew transportation to the ISS must be done in one step. To skeptics, this approach does not represent a transition from government systems to commercial services as much as it does an abrupt abandonment of tested systems and operations in favor of untested systems and operations.

Recommendation: Instead of mandating that the transition to commercial services occur in a single step, NASA should consider an approach that allows commercial service providers (CSPs) to gradually prove themselves capable of delivering of safe and reliable services before taking over the entire earth to Low Earth Orbit (LEO) transportation mission.

First, Elements: In this approach, NASA would start as the overall system integrator and operator, procuring the spacecraft and launch vehicles from commercial providers where they exist, and via collaborative development programs where necessary.

Then, Systems: Once those elements have been flight proven as a system, NASA could turn flight system acquisition and integration and launch responsibility over to commercial service providers, while retaining mission integration and operations responsibilities in a manner that enables NASA expertise to be gradually transferred to CSP Integration and Operation (I&O) functions.

Finally, Missions: Subsequently, and only after the commercial service providers have then demonstrated capability for mission I&O, the entire mission would be turned over to private industry.

Benefits of this approach

This phased transition approach may take several years longer to get to the final full commercial service model, relative to the “single step” underlying the President’s 2011 budget request for a commercial crew development program. However, the benefits of this approach outweigh the extra time and additional costs, because it may be the only approach that has a reasonable probability of achieving the ultimate goal of robust and safe commercial LEO transportation services while leveraging and retaining critical NASA skills and infrastructure that will be needed for space exploration beyond LEO.

| A programmatic approach to transitioning LEO transportation services that leverages the national assets of expertise and capability built up over 50 years of spaceflight systems integration and mission operations is the best insurance policy available to the nation and to the CSPs themselves. |

It is important to note that this phased approach does not alter any of the basic tenets of the Commercial Crew Development Program (CCDP) being developed by NASA. Chief among these tenets is that private companies will invest in and retain design ownership of their space systems. Furthermore, no aspect of the phased transition should be taken as justification for a “holding pattern”, where companies get stuck in Phases I or II while they satisfy innumerable requirements for safety, reliability, or skills acquisition. NASA must write clear, concise requirements for this program that commercial firms can reasonably expect to execute without government interference. In addition, companies should be incentivized to meet these requirements in as straightforward and timely a manner as is feasible. Partnering with industry in this innovative manner could accelerate the availability of US human access to LEO, while reducing risk and strengthening the capabilities of the US commercial launch industry.

Safety and risk

Crew and vehicle safety are of paramount concern for NASA and for CSPs. One frequently stated objection to a transition to commercial providers is that this change will result in increased risk to the safety of crewmembers and vehicle, and an overall increased risk to mission success. However, risk is extremely difficult to characterize in complex systems, particularly before an extensive flight history is available. In other words, although much of the debate about CSPs has focused on the perception of increased risk relative to government-developed and -operated vehicles, there can be no quantification of risk beyond that provided by engineering risk assessments without an operational track record.

Some launch systems, such as those provided by United Launch Alliance (ULA), have extensive histories; however, these have not yet supported crewed missions. Simply put, there is no reason to believe that CSPs will produce and operate flight hardware that is any more or less “risky” than government-provided flight hardware—the opinions of CSP stakeholders (both skeptics and proponents) notwithstanding. A phased transition enables CSPs to prove their capability to manage risk associated with flight hardware and systems integration while assuming more and more responsibility and independence over time. It also provides CSPs with opportunity to develop their own safety culture—aligned with NASA’s safety requirements when NASA is the customer—and to incorporate innovative methods by which to meet those requirements over time.

| Downsizing the NASA contractor workforce as a result of the transition to commercial services in combination with the end the Shuttle Program will eliminate more jobs than initially will be created in the new space industry. However, a phased transition softens the impact of this change somewhat. |

While much of the debate to date has focused on whether or not CSP systems themselves are inherently more vulnerable (“risky”) than government ones, mission I&O are every bit as critical to risk management as hardware and likewise can be fully assessed only over time. A programmatic approach to transitioning LEO transportation services that leverages the national assets of expertise and capability built up over 50 years of spaceflight systems integration and mission operations is the best insurance policy available to the nation and to the CSPs themselves. A phased approach that makes full use of these assets at the outset, then transfers them to CSP integrators and operators as appropriate, then finally releases CSPs to full responsibility for all aspects of each mission, meets this goal. It will also be critical to assure that CSPs are free to innovate as I&O expertise is transferred in order to reap the benefits of “next-gen” provider models for hardware and mission management. A transitional approach jointly provides opportunity to prove new approaches while continuing to benefit from well-established methods.

Workforce and skills retention

Another point of discussion among the broader space community has been the challenge of retaining the US industrial base and core capabilities, skills and expertise represented by the human spaceflight workforce. The challenges and necessity of doing so were summarized by A. Thomas Young, a retired executive with Lockheed Martin, in a recent statement:

“…spaceflight is not a typical technological activity. Because of the special characteristics of spaceflight… a workforce is required that has the culture and capabilities aligned with these characteristics. A workforce with the necessary intellectual strengths and possibly even more important, the experience and longevity to establish the sensitivity as to what is required for spaceflight success. Today in government, universities and industry we have such a workforce. It has evolved over decades of extraordinary successes and tragic failures… It is truly a national treasure. Without a challenging and meaningful space program, this national capability will atrophy.”

Development of a commercial space transportation capability relies on the workforce described by Mr. Young and others. Retention of significant portions of that workforce is therefore a necessary condition for its success, both in the short term with regard to meeting the goals of developing robust CSPs, but also to realize the longer-term goal of developing a vibrant commercial space market. The President’s Budget enables the development of a commercial space industry that will create new jobs and requirements for the specialized skill set extant in the current workforce. There is every reason to believe the demand for this unique workforce will grow over time: an analysis carried out by the Tauri Group in April 2010 estimated that the commercial space industry would develop up to 14,200 new jobs by FY12, assuming the President’s Budget request for the commercial crew and cargo programs is fully funded.

There is no debate that downsizing of the NASA contractor workforce as a result of the transition to commercial services in combination with the decision to end the Shuttle Program will eliminate more jobs than initially will be created in the new space industry. However, a phased transition softens the impact of this change somewhat by retaining those individuals with mission-critical skills and experience to support CSPs during the “Elements” and “Systems” phases of the plan. At the same time, that transition provides for ongoing engagement with spaceflight necessary to maintain those specialized skills. In this way the nation will continue to reap the benefits of its investment in the development of this specialized workforce as it first enables and then transitions to the burgeoning commercial space industry. Together with the President’s budget amendment of June 18, 2010, which transfers $100 million of Exploration funds to spur regional economic growth and job creation in Florida and other areas affected by the end of the Shuttle Program and the cancellation of the Constellation Program, the transition to commercial LEO transportation services as outlined here provides substantial support and opportunity for the nation’s spaceflight workforce.

Beyond Earth orbit

The President’s FY11 Budget “Adds $6B to NASA’s budget over 5 years and draws upon American ingenuity to enable us to embark upon an ambitious 21st Century program of human space exploration.” The cornerstone of this program is investment in game-changing technologies to enable the nation to explore space beyond earth orbit in an efficient and sustainable way, with Mars as the next major destination. Many of these have already been identified. In addition, many of the components and technologies created for existing programs will be carried forward. The Human Exploration Framework Team (HEFT) is charged with driving out the knowledge, capabilities, and infrastructure NASA needs to send people to explore multiple destinations in the solar system. Their findings will provide additional guidance to NASA’s technology development programs. The infrastructure and expertise resident in NASA exists in the context of a spaceflight culture developed over decades and possessed of hard-won insight and skill. Fifty years of development and execution of human spaceflight missions provides many of the building blocks upon which the nation will rely as it explores beyond Earth orbit. The evolution of a of a robust commercial space industry capable of managing transportation to and from LEO destinations has long been seen as a necessary precursor to furthering NASA’s reach to further regions of the Solar System. The maturation of commercial launch and cargo and crew transportation will reduce government resource investment in LEO operations, freeing it to explore beyond earth orbit. The “Elements”, then “Systems”, then “Missions” transition to commercial LEO services harvests the value inherent in the nation’s human spaceflight expertise and capabilities, utilizes it to ensure the successful development of a commercial space industry, and positions the agency for an exciting new era in space exploration.