Shuttle with racing stripesby Dwayne A. Day

|

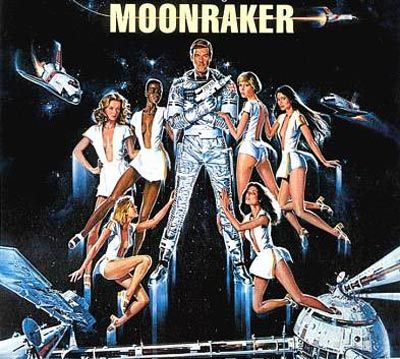

| The movie that made the shuttle an icon even before it flew was the 1979 James Bond film Moonraker. |

I’ve written in the past about my distaste for Bond movies, which I think are generally pretty lousy films (see “Bond, in orbit”, The Space Review, January 8, 2007). To summarize the things I dislike about them: the megalomaniacal billionaire bent on world destruction at the center of virtually every plot, the lame double-entendres, the blatant sexism, the dumb quips Bond makes upon dispatching a bad guy, the amazing coincidence that Bond happens to possess exactly the right gizmo he needs at the moment, and the absurdity of a “spy” with brand name recognition whom everybody knows the second he walks through the door. In other words, I hate pretty much everything about them.

But I like Moonraker, at least a little bit, and it has to do with the shuttles. Moonraker has lots of them. And they’re awesome.

Roger Moore has stated on several occasions that he viewed the Bond franchise essentially as camp, and so he played the character that way. Moonraker’s director, Lewis Gilbert, has also said that the production team did not think that the movies were supposed to be taken seriously. But the films are not played as obvious parodies or comedies. When I first saw the movie as a kid I had a hard time processing the campiness, and apparently I’m not alone in that.

I know the exact day that I first saw Moonraker at the theater. In fact, I know the exact time too. I know this not because it left a major impression on my young mind, but because when my mother dropped me and a friend off at the movie theater Skylab was falling out of orbit, and when she picked us up, it had reentered. That was kind of a punctuation mark for me—I was disappointed that NASA had not found a way to save Skylab and reuse it, and yet the Space Shuttle seemed like it would answer all of our hopes, launching regularly and easily and building a future space station in the sky. (Yeah, I was pretty young.)

The film was weakened by several things. For starters, it is pretty much a repeat of the previous Bond movie, The Spy Who Loved Me. The story is that a rich industrialist has decided to kill everybody on the planet. In Spy the rich guy is obsessed with the oceans and so he wants sea life to thrive, and figures that Global Thermonuclear War™ is the best way to achieve this. In Moonraker, the billionaire, named Hugo Drax, is a little less fish-focused and a little kinkier and wants to repopulate the planet with a race of superior beings who he has selected based upon their long legs.

The movie starts with a space shuttle on the back of a 747. Two stowaways on the orbiter emerge and climb into the cockpit. They fire up the shuttle’s engines and fly away, blowing up the 747 in the process. Bond then gets put on the case, sent to California to “investigate” why no shuttle was found in the wreckage. (It’s not clear why the bad guys hijacked the shuttle over the Canadian Yukon, rather than the ocean, where shuttle wreckage would have been much harder to find.)

Bond ends up at Drax Industries in the Mojave Desert, which manufactures the space shuttles for NASA. He is initially shown around by Drax’s “humble helicopter pilot” Corinne Dufour, played by the lovely Corinne Cléry. Although she gets my vote for prettiest woman in the film (it was not until decades later that I learned that she had a somewhat risqué reputation in her own country), she soon suffered one of the more ignominious Bond Girl deaths: eaten by Dobermans.

Of course Bond becomes a target, but Drax seems to be incapable of just sending a couple of goons to shoot him. Bond then bops around to Venice, then to Rio de Janeiro, then to the Amazon rain forest. In the rain forest he discovers Drax’s huge underground lair, which is where the billionaire plans to launch several space shuttles.

The clichéd Bond escapes are frequently absurd—after Bond poisons Drax’s pet anaconda, Drax drolly states, “You defy all my attempts to plan an amusing death for you.” Of course, he delivers the line while flanked by two machine-gun-toting guards who he then could have ordered to shoot the pesky spy, but doesn’t.

| The producers had extensive cooperation from NASA, including visits to both Johnson Space Center and Ames in California, although no NASA facilities appear in the film. |

Bond and his CIA agent partner stow away on a shuttle and end up at Drax’s orbiting space station. The gorgeous women who have appeared throughout the movie (who never say anything, which is probably all for the best since we never learn that the future mothers of humanity have the intelligence of supermodels) all show up as well. They are always seen in low-cut tops and miniskirts, which seems entirely impractical once they reach orbit. On the station Drax announces his plans to kill everybody on Earth and then repopulate it with his relatively small group of lithesome babes and their boyfriends while his space station orbits overhead demonstrating that “there is law and order in the universe.” One gets the sense that although he’s an aspiring genocidal maniac, Drax is also a bit of a perv.

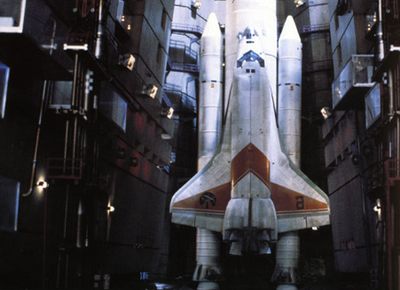

A Moonraker space shuttle, featuring “racing stripes”, prepares for launch. |

Making Moonraker fly

Moonraker was made because producer Cubby Broccoli saw the box office returns from Star Wars and decided that his next Bond movie should be set in space. It paid off handsomely, with a worldwide gross of $210 million in then-year dollars. Although Moonraker frequently rates among the worst Bond movies, it made lots of money, more than any other Bond film for the next 16 years.

This was not the first Bond movie to feature a space theme. In fact, a space aspect—such as a killer satellite—was common to many Bond plots, although that has faded along with the diminishing cultural influence of spaceflight. Before Moonraker, You Only Live Twice and Diamonds Are Forever involved space in some way, the latter movie featuring a diamond-covered satellite that was undoubtedly still cheaper than the James Webb Space Telescope.

It was common for Bond productions to announce a premier date, select exotic locations, and even start working on action sequences before they had a draft script. That was certainly the case with Moonraker and both the Rio de Janeiro location and the opening aerial fight scene were selected before the script was written and feel somewhat shoehorned into the story. The script was written by a committee. That does not mean that the scriptwriting was always crude, however. In a clever bit of backstory, the nerve gas that Drax plans on using is extracted from an Amazonian orchid which paradoxically killed the rain forest tribe that cultivated it, leaving the ruins that Drax then adopted as his Moonraker launch sites.

Of course, with such a vast production, involving four studios, seven countries, and three continents, not everything went smoothly. The Rio cable car filming nearly fell apart when the owner of the cable car company concluded that it would ruin his business and physically tried to stop the shooting. The filmmakers were talked out of suing him after being informed by a lawyer that in Brazil “litigation is like a knife fight in the dark—anyone can win.”

The producers had extensive cooperation from NASA, including visits to both Johnson Space Center and Ames in California, although no NASA facilities appear in the film. They also appear to have shot some exterior scenes at hangar facilities in Palmdale in the Mojave Desert. Due to some punitive taxation policies in the United Kingdom at the time, the production moved from England to France where it took over every available stage in Paris.

The two primary characters other than Bond are CIA agent/astronaut Holly Goodhead (played by Lois Chiles) and Drax (played by Michael Lonsdale). Both actors are exceedingly dull in their roles, although the same has been said about Roger Moore in the lead.

Lonsdale (like Cléry) was chosen because French regulations required that the production hire some French actors, and Lonsdale spoke excellent English. But he delivered his lines with palpable boredom and you almost expect him to start snoring in the middle of a megalomaniacal monologue. One of the producers speaking on the DVD commentary admitted that Lonsdale was “So laid back he was almost horizontal.” It certainly would have been a lot more interesting if he had taken to his task with a little more zeal. After all, he’s about to kill billions of people, so you’d think he would be a little more enthusiastic. Even Stalin had a sense of humor.

| Although the special effects are pretty good for the time, what really made the movie shine was the set design and model work. |

As for Chiles, one gets the sense that the actress—who had turned down a previous Bond movie role—really did not want to be in this film. She has no chemistry with Roger Moore, and she spoke her dialogue as if she was answering phones at the Department of Motor Vehicles. Perhaps she had visions of being a serious actress and was not thrilled when her agent got her the role of “Bond Girl,” even if this Bond Girl was supposed to be super-smart and trained to kill. She could have shown at least a little energy. (Of course, the other extreme is Denise Richards, enthusiastic and bubbly and totally unconvincing as nuclear physicist Christmas Jones in The World is Not Enough.)

One scene that was shot but did not make it into the film, nor any of the DVD extras (but does appear in some production photos), is a zero-g sex scene on the space station. Perhaps the editor considered it extraneous, or perhaps they had a hard time hiding the suspension wires.

Moonraker was the most expensive Bond film made at that point, with a cost of $32 million, more than the cost of the first six Bond movies combined. But the filmmakers balked at the exorbitant rate that an unnamed special effects company wanted to charge them for the space sequences, so they decided to film them in-house. At a time when computer-controlled cameras were becoming common for special effects, they ended up using a decidedly old-fashioned technique of shooting a single special effects element, like a shuttle moving across the frame, then stopping the camera and winding the film back, introducing another element to the shot, and filming it again. Of course, this dramatically increased the risk that they would break or scratch the film, or accidentally expose it, or somehow ruin multiple hours or even days of work. One particularly complex space battle sequence involved dozens of elements, and they ended up treating that bit of film as if it was worth its weight in gold.

Although the special effects are pretty good for the time, what really made the movie shine was the set design and model work. The sets, particularly Drax’s Amazonian lair and the space station interiors, are excellent. The French set builders were supposedly so excited by them that they defied their union and worked overtime and weekends to complete them.

| Even if it showed space shuttles in the service of a maniacal murderer, it still showed them flying—which was more than could be said of the agency’s own shuttle fleet, which at the time was experiencing some embarrassing problems. |

The model work, done by the late, great Derek Meddings, is so good that it represents probably the most realistic depiction of the shuttle until Space Cowboys, twenty years later. To simulate shuttle launches, the effects people used magnesium flares and projector bulbs to get the brightness of the engines, although they did not include the incredible smoke trails common to shuttle launches. Another inaccuracy is that the shuttle doors remain closed while the orbiters are in space. However, the Moonraker shuttles are cooler than NASA’s shuttles because they have nifty orange “go faster” stripes on their sides and wings. (The only thing better would have been if they had featured flaming bunnies.)

Drax’s odd-looking space station was a reaction against 2001: A Space Odyssey’s famous wheel. Instead, the designer wanted it to look like a mobile. In a nod to the requirement for artificial gravity, they spun the station, but even the filmmakers acknowledged that it didn’t make much sense and they primarily wanted it to look “pretty.” Eventually they blew it up in an inventive way, blasting away at it with shotguns on a closed set.

The filmmakers’ original goal was for the movie to debut at the same time as NASA’s space shuttle took flight, thereby riding on that publicity. But the shuttle’s launch date slipped out of 1979 and 1980 and the shuttle did not launch until April 1981. Nevertheless, Moonraker can probably be credited with giving the shuttle its widest public exposure before it actually began flying and it was probably a positive bit of public relations for NASA. Even if it showed space shuttles in the service of a maniacal murderer, it still showed them flying—which was more than could be said of the agency’s own shuttle fleet, which at the time was experiencing some embarrassing problems. Unfortunately, NASA never caught on to how cool it would have been to paint racing stripes on its own shuttles.