Gazing back through the crystal ballby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Despite the title, Easterbrook’s article represents a solid piece of research, although it helps to recognize what it was and what it was not. |

Gregg Easterbrook has been writing about the American space program off and on for three decades now. Although some of his articles have been very prominent—his article about dangerous asteroids was the cover story for the June 2008 issue of The Atlantic—they frequently draw withering criticism from the space community for their often bald-faced, erroneous assertions and the sloppy way that he interprets facts and figures to support his conclusions. Nevertheless, Easterbrook, who has devoted much of his attention to writing about sports in the past several decades, has often been regarded by his fellow journalists as a “space policy expert”, somebody that they relied upon for a critical, supposedly objective view of the American space program. The reason is because of an article he published in April 1980 that many journalists later (not quite accurately) came to believe predicted the failure of the solid rocket boosters on the Challenger almost six years later.

Before getting into the details of the article, however, it is useful to note that there has always been a pecking order for publishing, or at least different castes in the publishing world. At the top are the major news and opinion magazines and publications that print long essays. The people who write for these publications tend to be excellent writers capable of producing beautiful sentences. They also tend to run around in the same literary circles and they all know each other’s work. Farther down the pyramid are the gumshoes and the trade reporters, the people who often get out of their offices to cover a story rather than doing all their research over the phone, and develop long-standing relationships with their sources and deep understanding of the topics that they cover day in and day out. Someone like Easterbrook was in the upper tier. The trade reporters may cover their subjects in great detail and have tremendous knowledge, but they don’t usually cross over into the literary elite and get the big writing commissions and book deals. When Easterbrook wrote his article on the shuttle he was not saying anything that had not already been covered in the trade press. But he wrote in a fluid, engaging style. Because of this, his fellow reporters started to consider him an expert, even though members of the trade press probably had a different view at the time.

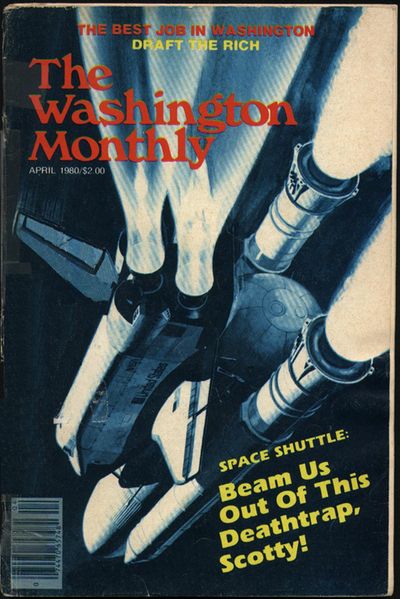

Easterbrook’s article appeared in the Washington Monthly under the rather muckraking headline “Beam Me Out of This Death Trap, Scotty”. The text itself occasionally bordered on purple prose (“No more zillion-dollar towers of power crumbling into ashes downrange over the Azores!”), but it was never ever dull. Despite the title, the article represents a solid piece of research, although it helps to recognize what it was and what it was not.

The article was pretty accurate at predicting many of the problems with shuttle that would eventually crop up, and recounting all of those that already had. As a matter of fact, by the time Easterbrook wrote it, most of the shuttle’s technical problems had been fixed and its development was nearing completion. In the article Easterbrook quoted a shuttle official who claimed that first flight would occur by late 1980 or the first quarter of 1981. It launched in April 1981. Of course, it was already several years behind schedule, and as Easterbrook noted, in March 1979 NASA had predicted a December 1979 launch.

| What he did not do was predict the problems that led to the Challenger accident, nor even any specific vulnerabilities of solid rocket boosters. |

Easterbrook also conceded that if the shuttle did not cost significantly more than it already had, then its development costs could not be considered outrageous. He was right. There are lots of things that you can bash shuttle for, but its development costs were relatively good. It was only about 17 percent over the estimate, which is pretty amazing considering the difficulty of the task, and pretty amazing when compared to so many other spacecraft (look at JWST and MSL, which are both significantly higher than their original estimates). It’s even pretty amazing when compared to other major government public works projects that don’t involve high technology, but still often blow past their cost estimates.

Easterbrook systematically demolished many claims for the shuttle. He declared that:

- it would not be cheaper to fly

- it would not achieve the high flight rates forecast for it

- it would not be able to retrieve obsolete or broken comsats for refurbishment (ones at GEO)

- it would never fly a large number of Spacelab missions

He was right on virtually all accounts. Of course, he was awfully snarky while making all of these points, but he was writing for Washington Monthly, not Aviation Week, and he was probably a 27-year-old journalist feeling his oats in the post-Watergate years.

Easterbrook didn’t get everything right. His cost estimates for shuttle development were not spot-on, although they were in the right direction. He predicted that the shuttle would not carry 65,000 pounds to orbit, but then quoted someone who said “We’ll be lucky if we hit 30,000 due-east.” The heaviest shuttle payload, the Chandra telescope, was a lot heavier than the pessimist predicted, weighing nearly 50,000 pounds.

There are a lot of good parts to the essay, but here’s the part where Easterbrook nailed it:

Technical problems are just that: technical. Much of what’s wrong with the shuttle will someday be fixed. If money is no object, as it usually isn’t in space launches, we can pay more for reusable shuttles than for throw-away rockets if we have to. But the question never answered is—what will the shuttle do that rockets couldn’t do?

It can’t launch more than they can; sometimes, it can’t launch as much. (Even the 65,000-pound target pales compared to the 250,000 pounds a Saturn V could hoist.) It can’t bring back satellites. It can’t keep a space station aloft even a fraction as long as Skylab stayed up there. It has no scientific value. It just has men in the front seats… and an enormous amount of weight and equipment devoted to bringing them, and an empty cargo bay, back in one piece.

There is something noteworthy a rocket can do that the shuttle cannot. A rocket can be permitted to fail. What if a billion dollar spaceship wipes out on a “routine” mission “commuting” to space with some puny little satellite? [Former astronaut Richard] Cooper fears it might drive a stake through the heart of the manned space program. Would the public stand to lose a quarter of the fleet in a single day? Would it fork over another billion dollars to build a replacement? Would it stand for spending millions to train astronauts to be truck drivers, only to lose truck and drivers both? The prospect makes the old rockets seem kind of nice. One of the old throw-away jobs could go haywire, and spiral down into the ocean off the Bahamas, and everybody would feel miserable and millions would be wasted and everybody would go back to work. Lost it, dammit—but then nobody ever expected it back.

Yes, he got that right.

What he did not do was predict the problems that led to the Challenger accident, nor even any specific vulnerabilities of solid rocket boosters. Here’s what he wrote about the SRBs:

Here’s the plan. Suppose one of the solid-fueled boosters fails. The plan is, you die. Solid rockets can fail in two ways. They can explode; enough said. Or they can shut down spontaneously. If a booster shuts down, there will be 2.5 million pounds of thrust on one side battling zero pounds on the other. Even a split second of this imbalance will send the ship twisting into oblivion, overriding any application of pilot skill.

Yes, he was pointing out that an SRB failure would be fatal. But he indicated that a lot of things involving the shuttle could be fatal. The Space Shuttle Main Engines had a difficult development history; if they blew up, it could be fatal too. And if the tiles fell off the shuttle, that could be fatal as well. The article predicted a lot of different things could go wrong, included a few qualifiers that they might not, and noted that there was no escape system, which was really the most important point.

But how insightful is that? You could write something equally as alarming about commercial airliners, which have failed in multiple ways over many decades (wings and engines falling off, cabins bursting open, avionics malfunctioning) and also have no escape systems. But what is the difference between a commercial airliner and a space shuttle when it comes to safety? That’s a complex question.

| When Columbia came apart in February 2003 he wrote an article for Time magazine about the shuttle and he could barely contain his sneering. |

When Challenger blew up in January 1986, Easterbrook’s 1980 article made him seem clairvoyant to people who didn’t follow space very closely. After that, he would write articles about NASA every year or two and he would always bash the agency. Many of those articles were more semi-informed commentary pieces than actual reporting. His articles frequently contained at least one major mistake or misunderstanding. He was always rushing so fast to condemn NASA that he did not bother to check his facts, or didn’t want the facts to get in the way of his story, and it seems likely that NASA officials were probably not quick to return his phone calls to help him get it right.

When Columbia came apart in February 2003 he wrote an article for Time magazine about the shuttle and he could barely contain his sneering. Considering how quickly the issue was produced, he must have written his article the day of the accident, without doing any research. It’s part of the journalist job description to write about accidents and death, but it was hard not to read his Time article and conclude that when he saw the news reports about Columbia, he also saw an opportunity to sell a story.

Similarly, after Bush announced the Vision for Space Exploration, Easterbrook wrote a blog post attacking it. He then did some simple math to come up with a high price tag. I wrote a piece deconstructing his article, pointing out, for instance, that he double-counted $200 billion and then rounded up by another $200 billion to reach a trillion-dollar price tag (see “Whispers in an echo chamber”, The Space Review, March 22, 2004). It was hard not to conclude that he was more interested in bashing NASA than being accurate.

Easterbrook doesn’t write much about space anymore—once every couple of years—but when he does he still commits whoppers. His 2008 Atlantic article about asteroids is an example of Easterbrook at his worst, filled with assertions about what NASA “should” be doing, in his opinion, without noting that his opinion is not shared by the political officials who ultimately set NASA policy. He is not the kind of journalist that people in the space community take seriously, because they know that he’s largely a hit-and-run artist: he takes a shot (“NASA sucks”) and then goes on to another beat. There are other reporters who spend a lot of time in this field who are better respected, and if they criticize NASA, they are taken more seriously.

But all that said, back in 1980, Easterbrook gazed through the crystal ball, and saw a cloudy future for the shuttle—and he was right.