|

|

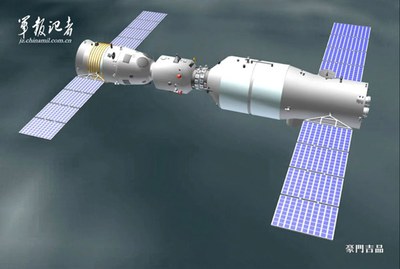

As China’s space capabilities grow, including the upcoming docking of an unmanned Shenzhou spacecraft with the Tiangong-1 module, Western analysts struggle to classify various schools of thought on Chinese space policy. |

A new policy typology to better understand the goals of China’s space program

by Danny Houpt

Monday, October 31, 2011

Existing literature on outer space policy typologies has focused almost exclusively on the weaponization of space. Indeed, most views on space have been classified by academics as varying degrees of support or non-support for seeking a military edge in the heavens. However, these typologies ignore a range of other policy paths and goals that states pursue in space. China’s space program, one of the most important to watch in the coming decades, illuminates these differences well. A cursory look at China’s four primary space mission areas—civilian, diplomatic, commercial, and military—shows the variety of pursuits that are not focused on the weaponization of space. It is important that China be used as a vehicle to expand beyond the weaponization debate because there seems to be a pervasive view in the US and elsewhere that China views space largely through a military lens. Although China’s military does indeed seem to believe the weaponization of space is inevitable, there are competing interests in China’s space program that do not make this a foregone conclusion. To better conceptualize China’s space program and add to existing literature on outer space, a new policy typology is proposed that accounts for a more realistic and practical portrayal of states’ interest in outer space that includes commercial, diplomatic, and civilian pursuits as well as inevitable military interests.

Current space policy typologies

A number of academics have proposed theories and typologies to better conceptualize the realm of outer space. Some theories attempt to apply the tenets of established international relations theories and strategies to outer space affairs.1 The more discussed and established space theory authors, however, base their work around the unique characteristics of outer space, incorporating such factors as orbital mechanics. The crux of the debate in space theory and literature has largely been the weaponization of space. Indeed, for decades throughout the Cold War and beyond weaponization has been the focus of most academic work on outer space. Since no state has yet to weaponize space, nor fully agree to not weaponize space, most theories are normative. Most literature is also US-centric, giving recommendations directly to US policymakers in ways that are not fully applicable to other states, such as China. Many typologies have already been devised to represent the more tempered and accepted views on outer space. A standard typology usually includes a variation on the following schools of thought:2

-

Space Hawks: This group believes outer space is the “ultimate high ground” and that the US should pursue unrivaled dominance of the space domain.3 They in general oppose treaties that would limit the freedom of the US to weaponize space.4 Space Hawks justify this approach for military ends, not necessarily to encourage commercialization or enhance space exploration.

-

Inevitable Weaponizers: Whether or not weaponizing space is desirable or beneficial is a moot point to this group that believes space will inevitably become weaponized. This group also believes that US actions in favor or against weaponization will have little impact on whether or not other states seek the weaponization of space5. The US should therefore, even reluctantly, prepare accordingly.

-

Militarization Realist/Space Nationalists: This group opposes the weaponization of space because it would be detrimental to US security interests. In their view, instead of securing a strategic high ground, weaponizing space would allow other states to easily follow suit, thus sparking a space-based arms race and increasing instability in crisis situations. Furthermore, space-based weapons would be highly vulnerable to foreign strikes, thus unnecessarily putting at risk extremely costly space assets.

-

Space Doves: This group opposes the weaponization of space for moral, ideological, and other reasons “transcending defense policy considerations.”

| It is important that China be used as a vehicle to expand beyond the weaponization debate because there seems to be a pervasive view in the US and elsewhere that China views space largely through a military lens. |

The existing typologies represented above are helpful in simplifying the wide swath of views that exist on outer space. However, they are insufficient for analyzing China’s space policy. First, most theories and academic writings are US-centric and generally suggest measures that are currently out of China’s technological or economic reach. Secondly, being a newcomer to outer space and having to catch up to the US—who is decades ahead in terms of capability and critical thinking on outer space—adds an element that is not covered by existing typologies. Finally, the current typologies and literature are largely based around the weaponization of space. However, weaponizing space is only one possible policy among many others that factor into a governments decision making process. To account for the alternative perspective with which China approaches outer space policy, and better represent the multitude of non-military aspirations in space, it is best to develop a new typology that better fits China’s space policy. First, however, it is necessary to take a closer look at the individual aspects of China’s space program to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the views and policy goals that exist in China today.

Civilian space program

China has successfully completed a number of manned and unmanned outer space voyages and in 2003 became the third country, behind the former Soviet Union and the United States, to develop manned spaceflight independently. The pace of development in China’s manned space program shows no signs of slowing. Last month China launched Tiangong-1, which will serve as a target for space rendezvous and docking experiments. Reports suggest it will also house many new medical and science experiments. The Shenzhou-8 mission, expected to launch within days, is expected to attempt the nation’s first space docking. These are preliminary steps in the third phase of the manned space program, which the government claims will include a long-term manned space station by 2020.

China has also achieved many scientific milestones in space including a number micro-gravity scientific experiments and observations, though its most impressive achievements seem to come out of its lunar exploration efforts. The Chang’e-1 lunar orbit probe was launched in October 2007 and mapped the entire surface of the Moon. The follow-on Chang’e-2 orbiter carried out tests in advance of Chang’e-3, which is expected to conduct China’s first lunar landing. China also has plans to launch a microsatellite to Mars in November 2011, known as Yinghuo-1—its first deep-space venture, although flown as part of a larger Russian mission, Phobos-Grunt.

| China has also become, according to Handberg and Li, a “beacon for other economically and technologically challenged states” who are seeking to make their way into space. |

China’s civilian space program has gone beyond the obvious technological and scientific benefits in garnering a new image of China as a world power, much as the Apollo program did for the United States.6 Roger Handberg and Zhen Li, in a study of China’s space policy, insisted that China’s space technologies have three primary uses: civilian, military, and prestige.7 Prestige, they write, “arises from the employment of space technologies to enhance the state’s and governing elite’s international and domestic prestige.” The manned spaceflight missions, they note, have “helped change the backward image of the Chinese in the minds of other people and, concurrently, build Chinese national pride and self-confidence.” Space activities also boost employment, creating both high end engineering and design jobs, and more simple manufacturing jobs. Domestic pride and international prestige also give greater credence and legitimacy to the Chinese Community Party (CCP), which weighs heavily on the minds of leaders in Beijing.8

Diplomatic space policy

“Space has never been solely, or even primarily, about exploration. It has always been linked to other goals, usually related to foreign policy,” notes space policy expert Joan Johnson-Freese, a point that has not been lost on China. For decades China has held steadfast in its message to the international community that it is against the weaponization of outer space in an attempt to portray itself as a benign space power. Its primary medium for pushing this agenda is the United Nations Conference on Disarmament (CD). In 2008 China and Russia in jointly submitted the “Treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space, The Threat or Use of Force Against Outer Space Objects,” known by the acronym PPWT. This treaty seeks to supplement existing outer space treaties to further secure space as a sanctuary, free from weaponization. Article II of the draft treaty states:

States Parties undertake not to place in orbit around the Earth any objects carrying any kind of weapons, not to install such weapons on celestial bodies, and not to station such weapons in outer space in any other manner; not to resort to the threat or use of force against outer space objects; not to assist or encourage other state, groups of state or international organization to participate in activities prohibited by the Treaty.9

This statement is in fact the outcome of years of work on establishing an acceptable legal framework that began as a 2002 working paper China jointly submitted on the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space (PAROS).10 Upon release of the PAROS paper in 2002, Hu Xiaodi, Ambassador for Disarmament Affairs of China at the United Nations, said that the weaponization of space “will distract and even derail the peaceful use of outer space and further damage global strategic balance and stability, which is in no one’s interest. Preventing such a danger must be high on the agenda of the international community.”11 Interestingly, China’s diplomatic stance has not changed significantly since its 2007 ASAT test. China’s defense white paper released in March 2011 clearly states that “The Chinese government…opposes any weaponization of outer space and any arms race in outer space,” and says it that it is looking forward to discussing its PPWT treaty “at the earliest possible date, in order to conclude a new outer space treaty.”12

China also uses space as a way to attract allies and diplomatic partners. In 1992, China, along with Pakistan and Thailand, founded the Asia-Pacific Multilateral Cooperation in Space Technology and Applications to promote regional cooperation on space issues. In January 2003 the organization became the Asia-Pacific Multilateral Cooperation in Space (APSCO) and soon expanded membership to a handful of other nations including Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Iran. Space cooperation agreements have continued to multiply and China currently has an extensive list of space agreements and memorandums with countries across Asia and the world. “In sum,” concluded Gregory Metzler, “China’s space program has graduated from a research and development tool to one of diplomacy.”13

China has also become, according to Handberg and Li, a “beacon for other economically and technologically challenged states” who are seeking to make their way into space. China offers lower costs and fewer political restrictions to its space partners than do established spacefaring nations, making China an attractive partner for less advanced states or those that are politically unpalatable to Western space powers. Kevin Pollpeter notes that, “China’s satellite exports are not purely commercial transactions…and cannot be divorced from its diplomatic agenda. It is no coincidence that China’s two satellite export agreements are signed with countries with large oil reserves—Nigeria and Venezuela.”14

Commercial space policy

China’s 2000 white paper on its space activities clearly states that “the Chinese government has all along regarded the space industry as an integral part of the state’s comprehensive development strategy.” The follow-on 2006 white paper reiterates this call and expresses the determination of the Chinese to maintain long-term stable development in its space industry. In line with these statements, China has been slowly growing itself into a formidable commercial competitor in the space market.

| According to the government, “China considers the development of its space industry as a strategic way to enhance its economic, scientific, technological and national defense strength, as well as a cohesive force for the unity of the Chinese people, in order to rejuvenate China.” |

As of 2009 China’s commercial launch industry had 35 launches, 30 of which were for international customers from countries including Brazil, Australia, Indonesia, and even the US. By 2004 China was able to offer a full package to build, launch, and provide operating services for satellites. Nigeria was the first country to take up the offer that year, followed soon by Venezuela. China has also provided full launch and satellite services for Pakistan, Laos, and Bolivia. In 2010, China’s Long March rocket launched 15 successful missions, more than any previous year, signaling growth in China’s space launch capability and demand.

China’s portion of the space market remains small. Nevertheless, China is beginning to overcome these barriers. By focusing on developing countries that cannot afford Western alternatives, China has been gaining experience in developing and launching satellites and gaining revenue and experience that will help enhance its market potential. In fact, this strategy is already beginning to pay off. The willingness of foreign nations to stonewall China’s commercial space venture is slowly deteriorating as countries across the world are increasingly attracted to China’s more economical space services.

China maintains a strong competitive advantage due to government ownership of the Great Wall Industrial Corporation and China’s low labor and manufacturing costs; its launch prices for commercial communications satellite are up to 40 percent less than most comparable systems. China is exploiting this advantage to carve a larger share of the space launch market, including in established markets such as Europe. In 2009 China secured its first deal in over a decade with a Western space operator, France’s Eutelsat, to launch a private communications satellite.

Greater commercialization of space applications is one of China’s long-term goals. It is planning to expand its share of the space market with its new series of Long March launchers. According to the government, “China considers the development of its space industry as a strategic way to enhance its economic, scientific, technological and national defense strength, as well as a cohesive force for the unity of the Chinese people, in order to rejuvenate China.”

page 2: military space missions >>

|

|