Telstar and the transparency of space successby Jeff Foust

|

| “In the history of engineering, this is one of the great systems integration achievements,” said Geselowitz of Telstar. “Even today, you look back and you say, ‘how did they do it?’” |

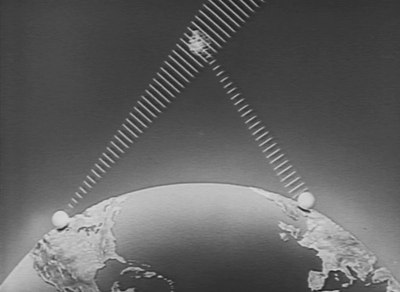

Actually, the broadcast of a game between the Philadelphia Phillies and Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field was just some filler until the main event planned for the day, a live press conference by President John F. Kennedy. That broadcast was the public debut of Telstar, although it had actually already transmitted video between the US and Europe shortly after its July 10, 1962, launch. It’s widely considered the beginning of an era in satellite communications that has revolutionized our world.

Telstar was, initially, a major technology accomplishment, demonstrating that a satellite could serve as a television (and other telecommunications) relay. “There were daunting technological barriers,” said Michael Geselowitz, senior director of the IEEE History Center, during a symposium about the 50th anniversary of Telstar at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC, earlier this month. That included the challenge of packing the electronics into a volume small enough that could be launched, operating the satellite once it was in orbit, and even the construction and operation of the ground stations that transmitted to and received signals from Telstar.

“There were so many firsts,” he continued, but added that the people who led the project believe the biggest challenge was the overall system engineering. “In the history of engineering, this is one of the great systems integration achievements… even today, you look back and you say, ‘how did they do it?’”

Once it made its public debut 50 years ago, Telstar became something of a cultural icon. “This led to a summer and a fall of 1962 where Telstar was regularly in the news,” said James Schwoch, professor of communications studies at Northwestern University, as it was used for a variety of international television exchanges. It even created some controversy. “Telstar rocked the fashion world by showing photographs of the 1962 fall Paris clothes designs earlier than they were supposed to be released and earlier than they had ever been released before,” he recalled. “There’s many of these kinds of stories.”

That cultural impact long outlived the satellite itself, which went out of service in 1963, its electronics battered by the radiation environment in low Earth orbit created by high-altitude nuclear tests. Its technical approach was also superseded by geosynchronous satellites, which became the preferred approach for satellite communications within several years. But the idea of using satellites to transmit television and other communications around the world, and the effect it could have on individuals and society, was firmly established by Telstar.

One demonstration of that was at the Telstar symposium itself this month, which featured a live video link—via satellite, of course—with the Cité des télécoms, a museum at Pleumeur-Bodou, France, which hosted one of the European ground stations used by Telstar. Dignitaries in both museums exchanged platitudes about Telstar and the effects of satellite communications, linked by a high-definition video transmission whose lag of a few seconds was the only hint of the distance between the two museums.

| Satellite communications has become part of the infrastructure of modern day society, and as a result it has become invisible on a day-to-day basis, just as other infrastructure technologies are. |

Yet, one of the remarkable things about the video link was that it was, in fact, relatively unremarkable. The idea of live television spanning the globe went from a culture-shocking novelty to a rather ordinary, even banal, experience within a half-century. “Today, of course, we live steeped in digital communications that inform us instantly about world events,” said G. Wayne Clough, Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution. “We take for granted that this is as it should be, and forget that the breakthrough that changed our world occurred just a short 50 years ago.”

That transition of satellite communications offers a lesson for space advocates and enthusiasts. Some of these people get frustrated by the fact that people don’t recognize the role that satellites play in everyday life in applications like communications. If only the average person better appreciated how satellites helped them connect with the world, they argue, he or she would better appreciate the other applications of satellites and spaceflight—and, thus, perhaps, be more willing to support additional funding for NASA.

That lack of appreciation, though, is a sign not of a failure of outreach, but instead a success of technology. People don’t think about communications satellites simply because the technology works, seamlessly providing them the information they need. The only time the public might think about communications satellites is if one fails, disrupting the flow of television programming or other data they’re distributing (recall the failure of the Galaxy 4 communications satellite in May 1998, which disrupted pager service—remember that?—for millions of customers in the US.)

Satellite communications has become part of the infrastructure of modern day society, and as a result it has become invisible on a day-to-day basis, just as other infrastructure technologies are. How often, for example, do you pause to wonder at the modern marvel of the power grid? Probably only when something goes wrong and cuts power to your home. You may not even known what power plant is supplying your electricity, in much the same way you don’t know what satellite provided the television show you’re watching—or even if a satellite was used at all. We are so used to satellite dishes that we no longer notice them in the landscape unless we encounter an unusually large or distinctive one, or else will ourselves to deliberately take note of them.

| Perhaps the biggest lesson of Telstar, then, is that space technology can change the world, even if the awareness of it as a space technology fades from the public’s perception. |

Communications is arguably the biggest business success story of the Space Age. The Satellite Industry Association estimates that, in 2011, the worldwide satellite industry generated $177.3 billion in revenues, with satellite services, from direct-to-home television to the leasing of satellite transponders to relay television programming or other data, accounting for over $107 billion of that. The things that usually come to mind when one thinks of the satellite industry—rockets and spacecraft—account for just over $16 billion in revenue.

The same is true for some other successful space services. Navigation services, provided by GPS and other satellite constellations, have quickly become an essential part of everyday life, and may some day make the concept of getting lost an anachronism. Yet people don’t think of GPS as a space service, and may not think much about it at all until it doesn’t work for some reason. Satellites have also revolutionized meteorology, improving the accuracy and time horizon of forecasting, but again they’re rarely thought of as space systems (there is a frequently told, if likely apocryphal, story of a congressman asking a NOAA official why they need all these weather satellites when they can simply turn on The Weather Channel like everyone else.)

Perhaps the biggest lesson of Telstar, then, is that space technology can change the world, even if the awareness of it as a space technology fades from the public’s perception. That can be a tough pill to swallow for those enthusiasts who are enamored with space for space’s sake, but applying that lesson elsewhere—particularly in areas like space launch that have not enjoyed the same degree of success as satellite communications—can open up new markets and create new opportunities, on Earth and in space.