A curious future for Mars explorationby Jeff Foust

|

| After Curiosity, though, the picture of Mars exploration resembles the initial hazy images taken by the rover after landing through dust-coated lens covers. |

For those involved with Curiosity, the answer is at least two years—and possibly many more—of science. The initial checkouts of the rover in the days after landing showed the spacecraft to be in good health, and a four-day software upgrade that started this weekend will get the rover ready to start moving across the surface and studying the Red Planet. Some of the initial images returned by Curiosity have already provided tantalizing hints of the quality of the data it will provide scientists and the public in the months and years to come.

After Curiosity, though, the picture of Mars exploration resembles the initial hazy images taken by the rover after landing through dust-coated lens covers. NASA’s Mars exploration program is in a state of flux, with missions beyond the 2013 launch of the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution Mission (MAVEN) orbiter yet to be identified. Can the success of Curiosity to date breathe new life—and more funding—into those efforts?

Replanning Mars exploration

The fiscal year 2013 budget proposal, released by the White House in February, put NASA’s long-term Mars plans into limbo. NASA had previously planned to cooperate with ESA on the ExoMars program, with ESA building an orbiter that NASA would launch in 2016, followed in 2018 by a jointly-developed lander mission with a rover. The rover would cache Martian rock and soil samples as the first step of a long-term sample return effort, fulfilling the top priority for large, or flagship, planetary science missions in last year’s planetary science decadal survey (see “Fighting for Mars”, The Space Review, March 26, 2012).

With NASA’s participation in ExoMars terminated (ESA is hoping to continue the program, perhaps in cooperation with Russia), the space agency in February created an independent committee, the Mars Program Planning Group (MPPG), to evaluate options for future Mars missions in the 2018 and 2020 launch opportunities. “The team will develop a plan that advances the priorities in the National Research Council's Decadal Survey, which puts sample return as the top scientific goal, and leverages NASA's research in enabling technology,” John Grunsfeld, NASA’s associate administrator for science, said at the time of the group’s creation.

The MPPG’s work is now nearing its conclusion. At a press conference at JPL shortly before the landing, Doug McCuistion, director of NASA’s Mars Exploration Program, said a final report (in “viewgraph” format) was due to NASA Headquarters by the end of this month, with a later public release. “We are putting together a schedule for when we go public with report. It will be a public report,” he said. That release will also be coordinated with briefings of people at the White House, on Capitol Hill, and in the Mars science community, he said.

| “The budget in ’18 is thin,” McCuistion said. “It probably can’t support a rover or a lander.” |

While the MPPG has largely been working out of public view, it has offered some hints about what it is considering. In a briefing last month to the science and human exploration and operations committees of the NASA Advisory Council, the MPPG said its proposals were constrained by the projected future budgets available for Mars exploration in the administration’s 2013 budget proposal. “Current Rover options not credible for 2018 within budget constraints,” the presentation slides note. An orbiter mission in 2018 would be more viable given the budget, it adds.

McCuistion concurred. “The budget in ’18 is thin,” he said. “It probably can’t support a rover or a lander.” However, he added that a rover mission would be “the next logical step” after Curiosity and the 2013 orbiter, MAVEN.

The MPPG presentation advocates for a scientific approach called “Seeking the Signs of Ancient Life”, a continuation of ongoing efforts, including Curiosity, that would include an eventual sample return mission. The group is looking at several options, including a mission to land at the same site as Curiosity in the early 2020s to collect samples for return to Earth as well as missions to other promising sites. Those missions would feature rovers with sizes somewhere between Curiosity and the earlier, smaller Mars Exploration Rovers (MERs), Spirit and Opportunity.

The MPPG’s report will be incorporated into planning for future missions by NASA, although McCuistion suggested it might not be until early next year before the agency makes any formal decisions on future Mars missions. “When we are public with that will depend on how it takes us to come up with that as well as the discussion internally, within the agency and within the Executive Office of the President, since it will all fit into 2014 budget process,” he said. That fiscal year 2014 budget proposal is due out in early 2013 if President Obama wins reelection, but would likely be delayed until the spring if Mitt Romney wins in November.

Debating sample return

The focus of the MPPG’s efforts is to find a way to support a sample return mission that would likely return samples in the 2020s. “Sample return provides a common frame of reference for advancing knowledge, technology and capability,” the presentation notes. That’s consistent with the decadal survey, which endorsed what it called the Mars Astrobiology Explorer-Cacher, or MAX-C, rover mission as the top-priority flagship provided it was part of a sample return effort.

Not everyone, though, is convinced of the importance of a robotic sample return mission as a vital scientific goal and a necessary precursor for human exploration. In a panel session at the International Mars Society Convention in Pasadena on August 3, Mars Society president Robert Zubrin suggested that this emphasis was misplaced.

“I believe the program has become overfocused on sample return,” Zubrin said. While he supported robotic exploration for Mars as a step towards human missions, he worried that trying to land on Mars, collect samples, place them into a rocket that launches them into Mars orbit for later retrieval and return to Earth may be too complex. “I think that extrapolating the robotic program to sample return is taking it beyond when it beneficially trades off against human exploration,” he said.

| “I do not see how sample return, as such, is vital for human exploration, and I think that saying that it is actually creates an obstacle to human exploration,” Zubrin said. |

Zubrin instead supports an “aggressive” program of rover missions, based on the highly-successful MERs. “Here we have a very successful system, why don’t we churn these things out, start sending two of them every two years to Mars, different locations with different instruments, conducing different kinds of investigations, make them into a workhorse,” he said. Doing so, he said, could reduce the cost of each mission to $200–400 million, far less than the estimated $2.5 billion cost of Curiosity.

Those at NASA and in the science community, though, still believe sample return is important. “From a scientific perspective, sample return is extremely important,” said Jim Green, director of NASA’s planetary sciences division, on that Mars Society panel. Such samples, he added, may also be essential to ensuring the safety of future human explorers. “We believe firmly we must bring back samples from Mars before we humans go there.”

“Sample return provides the next possible big, giant leap in Mars exploration,” said Jim Bell, a professor at Arizona State University and president of the board of directors of The Planetary Society. “Yes we could do more MERs,” he added, “but the ability to characterize samples in terrestrial laboratories far exceeds what we can do with a robotic laboratory in the Martian environment.”

Zubrin, though, was unconvinced by the science or human exploration arguments. “I do not see how sample return, as such, is vital for human exploration, and I think that saying that it is actually creates an obstacle to human exploration,” he said. “I’m all for sample return, but I’d like to do sample return from a human expedition.”

A Congressional advocate for Mars

All of the discussion about Mars program replanning and the need for sample return—as well as the consternation about the administration’s proposed 20-percent cut in NASA’s overall planetary sciences program in the 2013 budget proposal—took place prior to Curiosity’s successful landing on Mars. Does that success change the calculus of the Mars program?

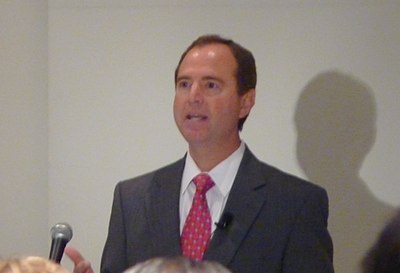

One person who hopes so is the Mars exploration program’s biggest advocate in Congress, Rep. Adam Schiff (D-CA). In comments both before and after the landing, Schiff, whose district includes JPL, made the case for restoring funding for Mars exploration as part of perhaps a broader strategic refocusing of the nation’s space program.

“We have too long drifted without a strategic vision for space that can survive changes of administration as well as congressional appropriations cycles,” he said in a speech at the Mars Society conference on August 4. With the arrival of Curiosity on Mars, “we face the urgent need to set new goals and reinvigorate the space program.”

Schiff said he believes a logical long-term goal for NASA’s exploration efforts is Mars. He said he thinks the MPPG will recommend a path that calls for a human landing on Mars by the 2030s, a decade after a sample return mission. (The MPPG presentation to the NASA Advisory Council does not mention this, beyond a reference “to achieve the goal of ‘humans in the Mars System’ by 2033 in the safest and most efficient manner,” a likely reference to President Obama’s goal from his April 2010 speech for a human mission to orbit Mars by the mid-2030s.) He called on attendees to petition their congressional representatives “for an increase in NASA’s budget as well as a national commitment to lead an effort to put humans on Mars by a date certain. Without persistence and clarity, we will continue to drift.”

| “I think frankly it has astounded the administration that you have spoken with such boldness and clarity,” Schiff said of the reaction to proposed NASA planetary science cuts. |

Schiff noted that House and Senate versions of the appropriations bill that funds NASA includes some additional money to offset, but not completely eliminate, the planetary sciences cut. “We still have a long way to go, and it is my hope that as we go to conference—if we go to conference—we can increase those numbers further,” he said, referring to the conference committee that will reconcile the House and Senate versions of that bill, unless the appropriations bill is combined with others into a larger omnibus bill. The threat of budget sequestration and a long-term continuing resolution that funds the government at 2012 levels for up to the first six months of fiscal year 2013 complicate those efforts, though, he said.

Schiff suggested that the White House was taken aback by the strong reaction to the proposed planetary cuts. “The only thing that has rescued us from the severity of what the administration proposed was the fact that planetary scientists like you have been making their voices heard and loudly,” he said, although most people in the audience at the Mars Society conference were space enthusiasts and activists, and not scientists. “And I think frankly it has astounded the administration that you have spoken with such boldness and clarity.”

After the Curiosity landing, Schiff reiterated his call for restored planetary funding. “This success must reinvigorate our efforts to restore funding for planetary science and future Mars missions,” he said in a statement the day after the landing. “Without the certainty of future missions and support, we will find it impossible to maintain the most specialized workforce on earth—the brilliant engineers and scientists who made this mission possible.”

In an op-ed in the Washington Post this weekend, Schiff also made the case for continued Mars exploration. “The success of the Curiosity landing will only intensify the pressure on NASA leaders to move forward and not rest on the laurels of a Mars program built up by others,” he wrote. Drawing an analogy to the Olympics, he concluded, “Last week, we won the gold. But where will we be in four years?”

For now, Mars scientists will content themselves with Curiosity and its potential to revolutionize science. For now, Curiosity has an official two-year mission, but many involved with the mission to expect it to last much longer. How long? Project scientist John Grotzinger noted that one of the MERs, Opportunity, is still operating on Mars eight and a half years after landing, while officially having only a 90-day mission. “No one would have guessed eight years, not even close,” he said in a talk at the Mars Society conference. As for Curiosity? “I sometimes wonder that maybe this rover will still be going when humans finally make it to Mars.”