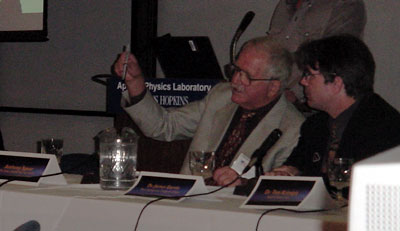

Why is Mars so hard?<< page 1: star-crossed history What’s wrong today?Given these failures, what’s the problem with Mars missions today? Are the spacecraft too technically ambitious, trying to do more than the current state-of-the-art technology permit? Or, are missions being squeezed by outside forces, trying to do more with less money and time? Those issues were debated last September during a panel session at the annual Military and Aerospace Programmable Logic Device (MAPLD) conference. The conference, held at the Applied Physics Laboratory (APL) of the Johns Hopkins University in Laurel, Maryland, devotes itself to technical analyses of electronics systems used on spacecraft and other systems, but this panel, titled “Why Is Mars So Hard?”, took a broader view of why Mars exploration has proven to be so difficult. Tony Spear, the project manager for Mars Pathfinder, believes that complex software is a major problem. “It is just as hard to do Mars missions now as it was in the mid-70s,” he said. “I’m a big believer that software hasn’t gone anywhere. There isn’t a project that gets their software done. Software is the number one problem.” As an example, Spear recounted a near-catastrophe that took place with Mars Pathfinder. “We struggled like crazy [with software] on Mars Pathfinder, and had the final software drop uploaded to the spacecraft a month before we landed,” he said. “And then, we almost forgot a patch [software bug fix]. We were under CNN surveillance, and we were wondering if the last patch got in!”

Spear also believes that a lack of progress developing new propulsion systems and materials also hurts Mars missions, making them try to do more with less usable mass to work with. Ed Euler of Lockheed Martin Astronautics, the company that has built several Mars missions, including MCO and MPL, agrees that mass is an issue. He notes that lander missions today use direct entry trajectories rather than going into Mars orbit first, like Viking, because of the mass penalties involved with the propulsion systems that would be required for orbit insertion. James Garvin, Mars program scientist at NASA headquarters, said that mass constraints will require more complicated subsystems for future sample return missions. “The limiting factor in Mars sample return is mass,” he said. “Direct return [of samples] from Mars right now exceeds the cost envelope and performance envelope of the available launch vehicles and upper stages.” While panelists generally agreed that technology poses a number of challenges for Mars missions, there was less agreement regarding how programmatic issues, such as cost, schedule, and management, may have contributed to recent failures. “The failures in the 1990s had clear-cut engineering causes,” said Stamatios Krimigis, head of the Space Department at APL. “These are linked to poor communications and management issues.”

“Faliures are simply due to human error, which is avoidable,” said Spear. “Under intense pressure, failure by project teams to get all the necessary thousands of things right causes the failure. Something either falls through the cracks or there’s a breakdown in teamwork.” He believes these pressures often come from “harassment” by management, trying to keep costs down and projects on schedule while coping with escalating requirements. “Mars 98 [MCO and MPL] was difficult from the word go: they were just unbelievably pressured by the fiscal constraints and they ran out of time.” Euler, who worked on Mars 98, disagreed somewhat with Spear’s assessment of the mission. “During the Mars 98 program we had no management harassment whatsoever from NASA or internally at Lockheed Martin,” he said. “We never had any problems with management, and we never had requirements creep.” Euler instead blamed the problems with Mars 98 with NASA’s decision to use less-powerful launch vehicles, forcing engineers to look for ways to cut mass. “This took up an enormous amount of resources during development that we could have used elsewhere solving some of these integration problems that eventually got us.” Euler, however, did end up agreeing with most of Spear’s argument about how the failures occurred. “It wasn’t bad engineering, it wasn’t unknown engineering, it was the errors that you and I make quite frequently, that someone else is always around to check you on,” he said. “Very good, solid engineers made mistakes, and we let those get through. It was the process that failed us, and the reason that happened is that we cut every corner to meet the cost challenges that we had.” “We certainly made sure that those processes will never let anything like that happen again, and we have a lot in place to make sure that never happens,” Euler said. |

|