Replacing the RD-180by Jeff Foust

|

| While SpaceX wasn’t shy about pointing out the use of Russian-manufactured engines, it didn’t specifically call for a ban on their import in its complaint. |

But what a difference a year—or even a few months—makes. Worsening relations with Russia over the Ukraine crisis have raised concerns that Russia could block exports of the engine to the US. For about a week earlier this month, the US effectively blocked RD-180 imports, thanks to a court injunction that spun out of SpaceX’s suit against the Air Force regarding competition in the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) program (see “SpaceX escalates the EELV debate”, The Space Review, April 28, 2014). Increasingly, the question is not whether the US needs to develop an RD-180 replacement, but if that engine should be a domestic copy or a new design, and just how long—and how expensive—that work would take.

Injunction dysfunction

In the last two weeks, the debate about the RD-180’s future has been tied to SpaceX’s case against the Air Force’s “block buy” contract with United Launch Alliance (ULA), which manufactures the Atlas V and Delta IV rockets. Even before SpaceX formally filed its complaint with the Court of Federal Claims on April 28, it suggested that payments to NPO Energomash, the Russian company that builds the RD-180 engines, could run afoul of sanctions against Russian government officials, including deputy prime minister Dmitry Rogozin, whose portfolio includes oversight of Russia’s space industry.

“In other words, under the ULA Contract, the Air Force is sending millions of dollars directly to an entity controlled by Russia and to an industry led by an individual identified for sanctions,” SpaceX stated in its formal complaint to the court. “It is hard to imagine any way in which entrenching reliance on Russian rocket engines while funding the Russian military industrial complex with U.S. tax dollars serves national security interests, especially at a time when the Administration has sanctioned individuals associated with the same military industrial complex over the Ukraine annexation.”

While SpaceX wasn’t shy about pointing out the use of Russian-manufactured engines, it didn’t specifically call for a ban on their import in its complaint, focusing instead on undoing the block buy contract and allowing the company to compete on all “single core” EELV launches. However, two days later, the court acted on its own, issuing a preliminary injunction blocking payments by the government and ULA to and from Energomash.

The injunction on payments to Energomash, Judge Susan Braden wrote in her order, would remain in place “unless and until the court receives the opinion of the United States Department of the Treasury, and the United States Department of Commerce and United States Department of State, that any such purchases or payments will not directly or indirectly contravene Executive Order 13,661,” the executive order that levied the sanctions on Rogozin and other Russian officials.

By the following Tuesday, May 6, the three departments weighed in through separate letters. Officials with both the Treasury and State Departments concluded that the sanctions on Rogozin did not apply to RD-180 purchases since the government had not confirmed that Rogozin directly profited from them. The current executive order, wrote State Department principal deputy legal advisor Mary McLeod, requires the Treasury and State Departments “make an affirmative determination to trigger blocking by the ‘controlled by’ provisions of the order,” she wrote. “As of the date of this letter, no such determination has been made with respect to NPO Energomash.” The Treasury Department provided a similar assessment, while the Commerce Department deferred to the other two agencies.

| “Unfortunately, SpaceX has made many public but unfounded speculations to create negative perceptions of a competitor solely for purposes of its own self-interest,” ULA said. |

The Justice Department, serving as the defendant in the case, used the letters to file a motion calling for the injunction to be lifted. “The appended letters from those departments provide those opinions and, collectively, demonstrate that, as of the issuance of those letters, purchases from or payments to NPO Energomash would not directly or indirectly contravene Executive Order 13,661,” it stated.

While SpaceX didn’t originally request the injunction, it opposed the bid to lift it. “What [the] Defendant has provided instead with its motion are three nonresponsive letters stating that these agencies have simply not yet made any determination one way or the other regarding whether payments to NPO Energomash violate Executive Order 13,661,” it argued in a May 7 court filing. It argued that the injunction should remain in place until the State and Treasury Departments made a determination, one way or another, about Rogozin controlling Energomash.

ULA also jumped into the fray, criticizing SpaceX’s “self-serving request” to keep the injunction in place. “Lifting the injunction will cause no harm whatsoever to SpaceX,” ULA argued in a court filing late May 7. By contrast, “the preliminary injunction will, if left in place, inflict irreparable harm on ULS.” (ULS, or United Launch Services, is a wholly-owned subsidiary of ULA used in business dealings with the government.) The injunction, the company claimed, could affect “two competitive proposals now pending,” believed to be the use of the Atlas V by Boeing and Sierra Nevada Corporation in NASA’s commercial crew competition.

ULA also fired shots at SpaceX outside of the court proceedings. “Unfortunately, SpaceX has made many public but unfounded speculations to create negative perceptions of a competitor solely for purposes of its own self-interest,” the company said in a May 7 statement calling for the injunction to be lifted. “This frivolous lawsuit caused unnecessary distraction of our executive branch leaders during a sensitive national security crisis.”

Shortly after a hearing by the court on the morning of Thursday, May 8, Judge Braden agreed with the government and ULA, concluding that the letters provided by the court demonstrated that the sanctions against Rogozin did not apply. The decision did come with a caveat, though. “If the Government receives any indication, however, that purchases from or payment of money to NPO Energomash by ULS, ULA, or the United States Air Force will directly or indirectly contravene Executive Order 13,661, the Government will inform the court immediately,” she wrote.

Reproduce or replace?

While ULA is now free to continue purchasing RD-180 engines from Energomash (as long as Russia continues to allow the company to sell them), the dispute raised more questions about the long-term future of the engine and continued reliance on it. What seemed like a good deal in the 1990s—access to a powerful and relatively inexpensive engine—doesn’t look as good to many in Washington today, given the current state of relations with Russia and the reliance on the Atlas V to launch a large fraction of national security payloads.

The original deal to use the RD-180 on the Atlas V required Lockheed Martin to develop the capability to manufacture the engines in the United States as a backup should the Russian supply be disrupted. However, while RD AMROSS, the US-Russian joint venture established to procure RD-180 engines from Energomash for ULA, has a license to manufacture the engine in the US and much of the technical information, costs led industry and government to abandon those plans years ago.

| “Anyone who has ever been out on a test stand, testing their own rocket engine, knows that this is, at best, a five- or six-year process to bring it to fruition,” Griffin said of replacing the RD-180. |

“Just like everything else, though, it requires an investment. It’s a fairly sizable investment,” Bill Parsons, the president and CEO of RD AMROSS and a former director of the Kennedy Space Center, told Space News last November. “But they [Energomash] meet their contracts, they deliver on time and the price is a good price. You build that same engine in the U.S. and the price of that engine goes up.”

“The bottom line is that the DOD didn’t invest, industry didn’t invest, the Congress didn’t make them, and it never happened,” said Michael Griffin, the former NASA administrator and current chairman and CEO of Schafer Corporation, during a meeting of the FAA’s Commercial Space Transportation Advisory Committee (COMSTAC) on May 9 in Washington.

Besides speaking as a member of COMSTAC, Griffin served as deputy chair of the Defense Department’s RD-180 Study Group, which examined options to the current dependence on the Russian-built engine. Griffin said the group has completed its work and briefed senior administration officials on the results, and expected the final report to be publicly released soon.

Since the report was not yet public, Griffin couldn’t share its results, but he did offer his own views on the situation, including his belief that developing a replacement of some kind of the RD-180 is not something that can be done quickly. “Anyone who has ever been out on a test stand, testing their own rocket engine, knows that this is, at best, a five- or six-year process to bring it to fruition,” he said of the development time. “And it really doesn’t matter whether you’re producing, or returning to production, an existing design like the RD-180 or building your own.”

That timeframe matches up with other estimates provided by the Defense Department in recent months, which estimated that starting domestic RD-180 production would cost about $1 billion and take five years. With the current stockpile of engines sufficient for only about two years’ worth of Atlas V launches, Griffin said there would be an “enormous food fight” for access to the rocket among the various government programs should imports be cut off, with some programs forced to shift to the Delta IV and perhaps be significantly delayed.

Griffin said he was confident that the US had the capability to develop a domestic version of the RD-180 if needed. “There’s been enough investment in the US side to replicate the coating and metallurgy technology that goes into the RD-180,” he said. “I think the national-level question is not could we, but should we.” He noted that the license to produce the RD-180 in the US expires in 2022. “It might be renewed, but maybe it won’t.”

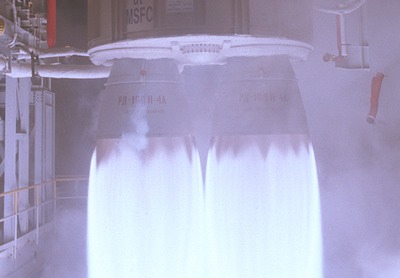

There are a number of options for US-designed large LOX/kerosene engines. Prior to the merger that created Aerojet Rocketdyne, the two companies were separately pursuing large engine programs for potential use on the advanced booster to power future versions of NASA’s Space Launch System heavy-lift rocket. Aerojet was studying a new engine design called the AJ-1E6 that uses LOX and kerosene propellants, while Rocketdyne, in cooperation with Dynetics, was looking at a modernized version of the F-1 engine from the Saturn V. If the scope of potential engines is expanded to other hydrocarbon fuels, SpaceX is studying an engine called Raptor that would be far more powerful than its existing Merlin engines, using LOX and methane rather than kerosene.

| “It will ultimately come down to what people—policymakers—decide what they want to have for a national security launch infrastructure,” Griffin said. |

Congress, after discussing the status of the RD-180 engine in a number of hearings over the last two months, is taking action. The House Armed Services Committee passed last week its fiscal year 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) that includes a provision calling for the development of a new liquid-propellant rocket engine for national security launches. The bill doesn’t specify it be a domestic version of the RD-180 or a new design, or, for that matter, it use LOX and hydrocarbon propellants, although the language strongly suggests it would be intended to be a replacement for the RD-180.

“The Secretary of Defense shall develop a next-generation liquid rocket engine that enables the effective, efficient, and expedient transition from the use of non-allied space launch engines to a domestic alternative for national security space launches,” the bill, as amended by the full committee on May 7, states (the original draft referred to the EELV program specifically, instead of the more general national security launch language.) The bill would authorize $220 million in fiscal year 2015 for the program, with the goal of having the engine, selected in “full and open competition,” be ready by 2019.

While that language passed the House committee, the Senate has yet to act on its version of a defense authorization, and neither chamber has started the appropriations process to actually pay for the study. However, if tensions with Russian remain high, the pressure could be on Congress to least kick off studies of an engine to eventually replace the RD-180.

At COMSTAC, though, Griffin said the engine debate touches upon a more strategic issue. “For national security purposes, we require two independent families of launch vehicles,” he said, referring to long-running national policy. Reality, though, has fallen short of that, he noted, such as the lack of an alternative to the Delta IV Heavy for the largest payloads. “Do we really want to have two families and pay the cost of that?”

Answering those questions, he said, will drive decisions on launch vehicle design and, ultimately, engines. Griffin didn’t attempt to answer the question about two launch vehicle families himself at the COMSTAC meeting, but said it would be the Defense Department, and not NASA or the commercial sector, that will drive that decision. “It will ultimately come down to what people—policymakers—decide what they want to have for a national security launch infrastructure.”