A new pathway to Marsby Jeff Foust

|

| “In essence here, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts,” said Lunine of the rationales for human space exploration. |

The latest effort to advise NASA’s human spaceflight program came last week, with a report by the Committee on Human Spaceflight of the National Research Council (NRC). Congress requested the report its the 2010 NASA authorization act, asking for “a review of the goals, core capabilities, and direction of human space flight.” The committee’s report, in broad terms, answers that request, offering insights into the hows and whys of human space exploration. But left hanging over the report is a central question: does the American public really support the human exploration of space to the degree necessary to enable sustained long-term programs?

From flexible path to pathways

Much of the report, formally titled “Pathways to Exploration: Rationales and Approaches for a U.S. Program of Human Space Exploration,” covers familiar ground. Like so many other studies, it endorses Mars as the long-term, or “horizon,” goal for human space exploration. “All long-range space programs, by all potential partners, for human space exploration converge on this goal,” the report states.

The committee examined the various rationales for human spaceflight and, like so many others in the past, failed to single all-encompassing answer. “No single rationale alone seems to justify the value of pursuing human spaceflight,” the report notes. Instead, the report endorses a mix of what it calls “pragmatic” reasons, such as economic benefits, national prestige, and scientific discovery, with “aspirational” reasons like survival of the species. (Human survival might sound like the ultimate pragmatic reason for human space exploration, but it has not been traditionally a driver of national policy in human spaceflight, and the report notes it’s “not possible to say whether human off-Earth settlements could eventually be developed” to achieve that goal.)

“In essence here, the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, and it is the aggregate of the aspirational and the pragmatic that, in the committee’s opinion, motivate human spaceflight and human space exploration,” said committee co-chair Jonathan Lunine of Cornell University at a briefing unveiling the report in Washington on June 4.

The report, like others, endorsed international cooperation in space exploration, although the committee argued that future cooperation in space exploration would have to be at a greater scale than previously. That would also mean, the committee concluded, cooperation with China, something that federal law currently forbids NASA from doing. “Given the rapid development of China’s capabilities in space, we concluded that it is in the best interest of the US to be open to China as a future partner,” Lunine said.

The biggest deviation from past studies, and NASA’s current plans, is in how to achieve that horizon goal of humans on Mars. It dismisses what it calls “capabilities-based” approaches, where technologies are developed “with no particular mission or set of missions in mind.” The “Flexible Path” concept described in the Augustine Committee’s 2009 report is considered a variant of that.

“Absent changes along the lines we are recommending, the goal of reaching Mars on any meaningful timeframe is itself unrealistic,” said the committee’s other co-chair, Mitch Daniels, president of Purdue University and former governor of Indiana.

“The program of record, we believe, will not be able to get us to the ultimate horizon goal in a foreseeable amount of time,” added Lunine. “We recommend a change to what we call a ‘pathways’ approach to human space exploration. This is a specific sequence of intermediate accomplishments and destination that lead to the horizon goal, and for which there is technology feed-forward from one mission to subsequent missions.”

The report included a set of “Pathway Principles” and “Decision Rules” that it argued NASA should follow when crafting that specific sequence of missions leading up to Mars. Those principles emphasize international cooperation and sustainability, among other aspects. The intermediate steps on the way to Mars should permit people “to see progress and develop confidence in NASA being able to execute the pathway” while remaining affordable and sustaining a suitable operational tempo of missions. The decision rules instruct NASA on when to start—or stop—specific pathways and how to choose what technologies to invest in given limited funds.

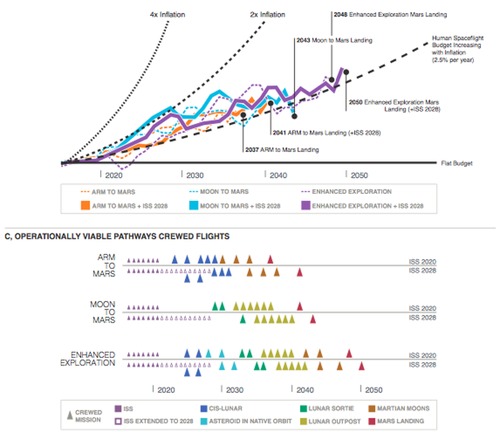

The report includes three sample pathways. One, “ARM-to-Mars,” is perhaps the closest to NASA’s current plans, featuring the Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM) followed by missions to Mars orbit and its moons, followed by a human landing on Mars. It is, perhaps, an oversimplification of NASA’s plans, since the agency in recent months has talked about a role for human missions in cislunar space after the ARM and before Mars, albeit not to the surface of the Moon (see “The uncertain road to Mars”, The Space Review, April 21, 2014).

| “I think the best way that I can put it is that we’re talking about a program that lasts decades and costs hundreds of billions of dollars,” said Sommerer. |

A second pathway, called “Moon-to-Mars,” skips the ARM in favor human missions to the surface of the Moon, including establishment of a surface outpost, before heading to the surface of Mars. A final pathway, “Enhanced Exploration,” is more of an all-of-the-above approach, including missions to the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point, a near Earth asteroid in a “native” orbit (i.e., not captured by the ARM), missions to the surface of the Moon and to the moons of Mars before finally landing on Mars.

The committee emphasized in its report that is was not recommending one pathway over another. However, some may come away from the report with a feeling that the committee was leaning towards those that included the Moon. Those architectures, the report noted, rate higher on many of the “Pathway Principles” attributes, including the significance of the destinations, the pace of missions, the development of technology needed to carry out the missions, and development risk in general.

The committee stopped short, though, of putting a price tag on any of the mission pathways included in the report, citing the wide range of variables in the pace at which the programs are pursued and when they are started. Indeed, some of the charts in the report showing spending over time did not include a y-axis quantifying the amount of money being spent. “I think the best way that I can put it is that we’re talking about a program that lasts decades and costs hundreds of billions of dollars,” said John Sommerer, who chaired the committee’s technical panel.

Reactions

The committee’s report generated a bit of an unusual reaction from NASA and Congress, who have often been at loggerheads in recent yards regarding the direction of the agency’s human spaceflight program. They treated the report as something of a Rorschach test, seeing very different things from the same document.

“After a preliminary review, we are pleased to find the NRC’s assessment and identification of compelling themes for human exploration are consistent with the bipartisan plan agreed to by Congress and the Administration in the NASA Authorization Act of 2010 and that we have been implementing ever since,” NASA said in a statement issued shortly after the report’s release.

| “The Obama Administration has failed to present a coherent plan to develop the capabilities and technologies required to support a human mission to Mars,” Rep. Smith said in response to the report. |

“There is a consensus that our horizon goal should be a human mission to Mars and the stepping stone and pathways thrust of the NRC report complements NASA’s ongoing approach,” the statement added. The NASA statement, though, made no mention of the report’s criticism of NASA’s current approach, including the rejection of the flexible path approach and a dim view the report took of the ARM’s role in furthering human missions to Mars.

Those criticisms, though, did not escape the leadership of the House Science Committee. “The Obama Administration has failed to present a coherent plan to develop the capabilities and technologies required to support a human mission to Mars,” the committee’s chairman, Rep. Lamar Smith (R-TX), said in a statement. He noted that a NASA authorization bill the committee passed—and due to be considered by the full House as soon as Monday—would require NASA to lay out a sequence of missions like the pathways in the report.

Smith also used the report to criticize ARM, something he and other members of his committee have been skeptical of. “This is a mission without a realistic budget, without a destination and without a certain launch date,” he said in the statement. “The Committee has heard a number of concerns about ARM, as well as promising alternatives such as a flyby mission to Mars and Venus in 2021.” However, the NRC’s report is silent on the concept of a Mars/Venus flyby mission in 2021, a variant of Dennis Tito’s Inspiration Mars concept (see “Mars 2021 and the quest for direction in human spaceflight”, The Space Review, March 3, 2014).

Democratic members of the committee also endorsed calls for the development of a roadmap of missions, as the authorization bill calls for. “Their report is clear—we are not going to have a human space exploration program worthy of this great nation if we continue down the current path of failing to provide the resources needed to make real progress and failing to embrace a clear goal and a pathway to achieving that goal,” said Rep. Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX), ranking member of the House Science Committee, in a statement.

In the Senate, though, the chairman of the Senate Commerce Committee’s space subcommittee offered a different assessment of the report. “This is affirmation that a mission to Mars is a go,” said Sen. Bill Nelson (D-FL), in a statement. “But as the report points out, we’ll have to give NASA sufficient resources to get this done.”

One outside expert was critical of the lack of details regarding international cooperation. In a talk June 5 at the Stimson Center in Washington, James Clay Moltz of the Naval Postgraduate School noted that while the report talked about importance of international cooperation in human space exploration, it didn’t go into details about how to achieve it.

| “This is affirmation that a mission to Mars is a go,” said Sen. Nelson. “But as the report points out, we’ll have to give NASA sufficient resources to get this done.” |

“It talked about the importance of international cooperation in the beginning, it talked about the importance of international cooperation at the end, but all of the analysis that it did in the middle about the budget and about the operational tempo and about the activities and the capabilities, it was all only the US program,” he said. “It didn’t consider the possibility of any sort of joint program in the human spaceflight area.”

At the briefing announcing the report, Lunine said the committee didn’t try to “constrain” what those international contributions could be, including whether any such contribitions should be on the critical path of the overall program. “We just pointed out that, because of the magnitude of the program overall, they will have to be themselves of a substantial magnitude.”

Fiscal fantasies

Another criticism that Moltz levied on the report had to do with budgets. “I was very surprised that the answer they came up with was, ‘Spend more money on NASA. Raise the NASA budget,’” he said. He felt that the guidelines of the report would have warned the committee to avoid what he considered a simplistic conclusion.

The report argued that budgets that only keep pace with inflation are insufficient to carry out the pathways included in the report. “With current flat or even inflation-adjusted budget projections for human spaceflight, there are no viable pathways to Mars,” the report stated. Such a projection “limits human spaceflight to LEO until after the end of the ISS program.”

Budget increases for NASA—or, at least, for its human spaceflight programs—at about double the rate of inflation would improve the situation. “Increasing NASA’s budget to allow increasing the human spaceflight budget by 5 percent per year would enable pathways with potentially viable mission rates, greatly reducing technical, cost, and schedule risk.”

The committee considered what it calls “operationally viable” pathways, a compromise between “schedule driven” concepts that the committee deemed unaffordable and “budget driven” scenarios that had too slow of an operational tempo. Those operationally viable pathways would land humans on Mars as early as 2037 in the ARM-to-Mars case where the International Space Station is retired in 2020; in the Enhanced Exploration pathway where the ISS operates to 2028, humans would make it to the Martian surface no sooner than 2050.

Those operationally viable pathways all fit into budget projections where the human spaceflight budget increases at no more than twice the rate of inflation, or five percent a year (the report assumes an inflation rate of 2.5 percent a year throughout the timeframe of the study.) The catch, though, is that the budgets would have to increase at five percent a year every year, for perhaps decades, a rate of growth that NASA has never sustained over the long term.

| “Given reasonable progress, we’ll see what we’ve seen in the past, which is retrospective public support,” Daniels said. |

That conclusion appears to clash with another finding of the report. The committee examined the long history of public opinion polls about space exploration. (The committee did not perform a new poll itself, although it did survey “stakeholders” in the space community.) The committee found that while polls showed general interest in space exploration, that interest did not translate into support for increased budgets.

“However, despite positive attitudes toward NASA, there is relatively little public support for increased spending for space exploration,” the report concluded. While the percentage of people who believe that the nation is spending too much on space has declined somewhat over the years, it remains higher than the percentage who believes the US is spending too little, a fraction that has remained relatively unchanged since the 1970s.

So how does the committee reconcile the requirement for long-term spending increases with a lack of public support for such increases? “We do not find that to be a stopper,” Daniels said, arguing that while there’s limited public support for increased spending, there’s also little in the way of strong opposition to such increased spending should policymakers decide to pursue them.

“Given reasonable progress, we’ll see what we’ve seen in the past, which is retrospective public support,” Daniels said. That was a reference to the support that the Apollo program had long after the end of the program, even though the program rarely had the support of the majority of the American public during the 1960s.

“The record from the ’60s suggests that, during the Apollo program, there wasn’t tremendous demand for the program, but there wasn’t tremendous opposition to it, and after it happened, the public felt good about it,” said Roger Tourangeau, who chaired the committee’s public and stakeholder opinions panel.

Daniel’s message was that there was a need for “strong and sustained national leadership” to move forward on a plan along one of the pathways laid out in the report, on the assumption that the public will follow.

“Our committee concluded that any human exploration program will only succeed if it is appropriately funded and receives a sustained commitment on the part of those who govern our nation,” Daniels elaborated in the statement accompanying the report. “That commitment cannot change direction election after election. Our elected leaders are the critical enablers of the nation’s investment in human spaceflight, and only they can assure that the leadership, personnel, governance, and resources are in place in our human exploration program.”

| “Asking future presidents to preserve rather than tinker with previously chosen pathways… may seem fanciful,” the report acknowledges. |

The report, though, is silent on how to create and maintain that commitment, a critical issue given the record of the last several decades of shifting direction from administration to administration in space policy. With the requirement to maintain steady budget increases over decades, and the tepid public support for space exploration, it becomes difficult to imagine multiple successive Administrations and Congresses staying on the same course given the short-term perturbations those policies will doubtless experience from now through the 2040s or 2050s.

“Asking future presidents to preserve rather than tinker with previously chosen pathways, or asking congresses present and future to aggressively fund human spaceflight with budgets that increase by more than the rate of inflation every year for decades, may seem fanciful,” the report acknowledges. “But it is no less so than imagining a magic rationale that ignites and then sustains a public demand that has never existed in the first place.”

But if the report rightly disabuses the reader of the existence of such “magic rationales,” it’s also hard for the reader to imagine the nation committed, technically and fiscally, to any of the report’s pathways over the next several decades. Unless the space community, along with political leadership on both ends of Pennsylvania Avenue, can come up with ways to develop and sustain that long-term political support, the recommendations of this committee, as thorough and well-intentioned as they may be, will end up atop the stack of other reports that have tried, and failed, to chart a long-term future for NASA’s human space exploration program.