Red tortoise, blue turtleby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Whereas in the past it was common for people to misinterpret Chinese comments about their robotic lunar plans as somehow related to human lunar plans, it is now starting to seem as if the two efforts may indeed be related. |

In fact, once you start looking back at this subject over the past decade, it becomes quite apparent that the Chinese government was both open and accurate about its human spaceflight and lunar exploration plans, even while concealing virtually everything about their military space program. As early as 2007 Chinese officials were discussing their plans for human spaceflight, indicating that the country would launch a series of increasingly ambitious human orbital spacecraft with the goal of developing a multi-component space station by 2020. Human lunar missions were not in their portfolio. However, they also indicated that they had a three-phase robotic lunar exploration plan. Phase I was to orbit the Moon with robotic spacecraft. Phase II was to land a rover on the Moon. And Phase III was to eventually conduct a robotic lunar sample return mission by 2017. (See “History doesn’t echo, it reverbs”, The Space Review, February 10, 2010.) The Chinese did not provide all of the details of their plans, but over time they revealed more information, and so far they have accomplished the first two phases.

What various Chinese officials have also repeatedly stated is that human lunar missions may eventually be in their future, but that the government will likely not make any decisions about that until after the multi-segment space station is operational, meaning sometime in the 2020s. Recently, Chen Lan wrote a detailed article for his web magazine “Go Taikonauts!” detailing China’s lunar studies. To date, Lan explained, these have primarily consisted of studies of large launch vehicle variants, rocket engines, and mission modes. But they’ve not committed to anything more. Lan should know, because he has consistently had some of the best and most prescient articles about China’s space plans.

Whereas in the past it was common for people to misinterpret Chinese comments about their robotic lunar plans as somehow related to human lunar plans, it is now starting to seem as if the two efforts may indeed be related. Simply put, China’s robotic lunar program is starting to look like a stalking horse for an eventual human lunar effort.

The most recent bit of evidence was the release of a photo showing the reentry vehicle for China’s robotic lunar sample return mission. The spacecraft, which is actually a test vehicle that should fly in 2015 prior to the 2017 sample return mission, looks remarkably like a scale model of the reentry capsule for China’s manned Shenzhou spacecraft. It also looks far larger than necessary to carry a few kilos of lunar dust and rocks.

| In contrast, the Chinese reentry vehicle is rather large. A human could actually climb inside it, although it is obviously not intended for that purpose. |

In December 2013, China landed the Chang’e-3 spacecraft on the Moon’s Mare Imbrium. The lander carried a small rover named Yutu, which unfortunately suffered a malfunction rendering it unable to move on the surface, although it still has the ability to transmit data back to Earth over six months later. Independent observers noted that the lander was far larger than necessary to carry the smallish Yutu. But China also indicated that Chang’e-3 was the first of a series of landers. CE-4 was likely to be similar to the CE-3 mission, also equipped with a rover. But CE-5, and possibly CE-6, would conduct sample return missions, meaning that they would require some kind of sampling mechanism, such as a scoop, as well as an ascent vehicle. Thus, Chang’e-3 was larger than needed for Yutu, but probably sized for the later sample return mission—a logical and methodical way to conduct robotic lunar missions.

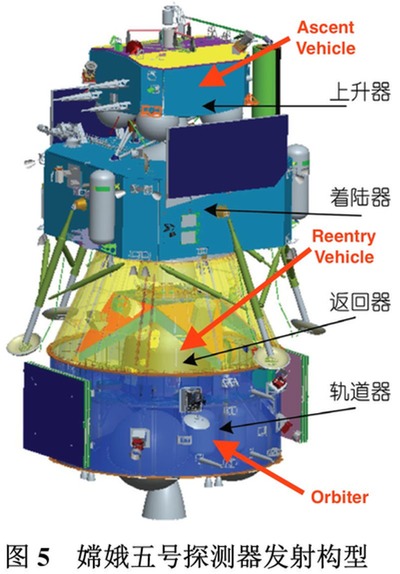

Illustration from a Chinese journal article showing the design of the planned Chang’e-5 lunar sample return mission. (credit: Science China Press) |

The Chinese have released some details of their Chang’e-5 lunar sample return mission profile. (A detailed article, in Chinese, can be downloaded here.) Rather than launching the samples straight from the Moon back to Earth, the plan is to put a large craft into lunar orbit and send the lander down. The samples would then be launched back into lunar orbit on an ascent spacecraft that would rendezvous with the mother craft. The samples would be transferred to the Earth reentry vehicle, which would be boosted out of lunar orbit and back to Earth. This will require a new, more powerful rocket currently under development. The mission model is similar to that used for Apollo. The advantage of this approach compared to launching the lunar samples directly from the Moon back to Earth is that it allows the lander to set down practically anywhere on the Moon, including the poles.

The Soviet Union conducted lunar sample return missions in the early 1970s. Their Earth reentry craft was relatively small. NASA has conducted both the Stardust and Genesis sample return missions, using reentry vehicles a little bigger than a car tire. The Goddard Space Flight Center is developing the OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission with a reentry vehicle similar in size to that used for Stardust. The Jet Propulsion Laboratory has proposed a lunar sample return mission that would have an Earth reentry vehicle probably a little smaller than the others.

In contrast, the Chinese reentry vehicle is rather large. A human could actually climb inside it, although it is obviously not intended for that purpose. A schematic of the lunar sample return mission shows this reentry vehicle nestled inside the orbital craft underneath the lander. The Chinese plan a separate test of their reentry capsule, putting it into a high orbit and then sending it back into the atmosphere at lunar return speed. They are nothing if not methodical.

Considering that CE-3 was a pathfinder for CE-5, it is not hard to imagine that the CE-5 reentry vehicle is intended to provide data for an eventual human spacecraft to return from lunar orbit. None of this indicates that the Chinese actually have a human lunar program. But if they can successfully complete a lunar sample return mission in 2017, it would position them to make a decision for a human lunar program in the 2020s. Chinese space officials could go to their country’s leadership and truthfully declare that they have proven they can land on the Moon, take off, rendezvous with a return vehicle in orbit, and then safely bring pieces of the Moon all the way back to Earth. From an engineering standpoint all they would need to do is scale up the systems and develop reliable life support, which should not be challenging considering the human spaceflight experience that they will also acquire during the remainder of this decade. A human lunar mission would not be cheap, but the robotic program will erase most of the technical barriers. It is an excellent risk reduction strategy.

| But if two tortoises are in a race, no matter how slow they’re moving, you should put your money on the one that is at least moving in a straight line. |

One of the things that has taken the wind out of the sails of those who previously warned of China’s impending human lunar landings is that China’s human spaceflight program has moved very slowly, with an average of two years between human launches. It is hard to whip up concern about an impending threat when the Chinese aren’t exactly sprinting along. They have a slow and deliberate pace

Of course, the same is true for NASA—at least the slowness part, anyway. NASA had a lunar return mission and then canceled it, and seems to get new human spaceflight goals every time the occupant of the White House changes. NASA is not racing anybody to the Moon. The turtle is still wandering around behind the start line.

But if two tortoises are in a race, no matter how slow they’re moving, you should put your money on the one that is at least moving in a straight line.