The 2014 PPWT: a new draft but with the same and different problemsby Michael Listner and Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan

|

| The draft treaty emphasizes a great deal on the placement of weapons in outer space, which would likely come in the form of co-orbital ASATs, but overlooks the more dangerous aspect of ground-based assets targeting outer space assets as demonstrated with the Chinese ASAT test in 2007. |

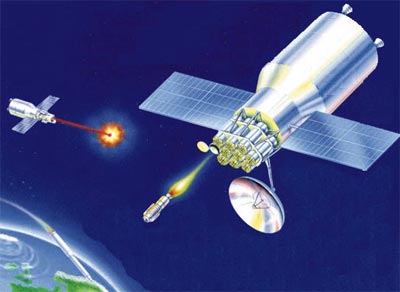

When they introduced the 2014 draft treaty, China and Russia offered an explanatory note. “We consider a legally binding ban on placement of weapons in outer space as one of the most important instruments of strengthening global stability and equal and indivisible security for all,” it stated. While this on its own is a worthy objective, there are several gaps that the PPWT does not address even in its latest draft. For example, the PPWT has not succeeded in receiving large-scale endorsement principally on the fact that the draft treaty does not address direct-ascent anti-satellite (ASAT) systems. nor does it address soft-kill weapons such as lasers that could be employed to permanently or temporarily disable a satellite. The draft fails to address so-called “breakout” weapons, which could take the form of direct-ascent or co-orbital weapons, that could be manufactured and launched in the event of hostilities. All these are inherently destabilizing and bear consideration yet remain unmentioned.

Rather, the draft treaty emphasizes a great deal on the placement of weapons in outer space, which would likely come in the form of co-orbital ASATs, but overlooks the more dangerous aspect of ground-based assets targeting outer space assets as demonstrated with the Chinese ASAT test in 2007 that targeted the defunct FY-1C weather satellite. Even though that test brought down one of China’s old weather satellites, the potential for intentional or unintentional incidents in the future is high and such capabilities raise the potential for dangerous consequences. Moreover, with recent revelations by the US Defense and State Departments that China has performed several disguised ASAT tests, it is clear that China has no intention of placing these weapon systems into the coverage of the PPWT.

The draft treaty also fails to address the major issue presented by space debris, which confronts the long-term sustainability of outer space, especially in low Earth orbit. The issue of space debris is not mentioned anywhere in the proposed draft treaty, even though the issue poses a far bigger challenge than the placement of weapons in outer space. The potential for any state placing weapons, including weapons of mass destruction (WMD), is highly remote, but the growth of space debris population has already affected the functioning of outer space assets. This issue is exacerbated by the continued threat posed by the destructive capacity of hard-kill, direct-ascent ASATs. The PPWT should acknowledge the importance surrounding the creation of space debris by direct-ascent ASATs, but the current draft conveniently neglects to mention it.

Ancillary to the issue of space debris creation is space debris removal. Technology designed to remediate space debris could also be used to interfere with functioning satellites belonging to another state. This so-called dual-use technology is already a political issue that needs to be overcome in order for effective remediation to begin. However, the PPWT would complicate the issue because it gives additional legal leverage to a State Party that seeks to protest activities of another to remediate space debris by claiming that it was a disguised “space weapon.” Whether such a claim is a legitimate concern or a geopolitical maneuver on the part of the complaining State Party, it will surely complicate the issue of space debris remediation. That the PPWT does not mention this concern is troubling and further degrades its legitimacy.

Some of the definitional attempts in the current draft of the PPWT pose challenges. For example, the manner in which “use of force” or “threat of force” is defined raises questions about the intentions of states that might become signatories of PPWT in the future. There is also an issue about the differentiation that the draft treaty makes between States Parties and non-States Parties. Article II states that States Parties to this Treaty shall “not resort to the threat or use of force against outer space objects of States Parties.” However, it makes no prohibition against the outer space objects belonging to non-State parties. This suggests that if the PPWT becomes binding international law, it will override customary norms of non-interference and leave the space objects of non-parties open to interference, unless they become party to the treaty.

| The PPWT should acknowledge the importance surrounding the creation of space debris by direct-ascent ASATs, but the current draft conveniently neglects to mention it. |

Additionally, the definition of “outer space object” used by the PPWT is superfluous and confusing, given that the Liability Convention and the Rescue Agreement have a working definition of “space object.” That definition is already internationally accepted and even used in some domestic space law, and would serve to integrate the PPWT into the current body of international space law. Having this new term defeats the purpose of trying to harmonize the PPWT with the existing international legal framework, which China and Russia are parties to, and suggests that the two countries seek to differentiate the PPWT from the existing body of international space law instead of integrating it.

Another inconsistency deals with the PPWT's reference to the self-defense provision in Article 51 of the UN Charter. China has objected in strong terms to the reference of Article 51 of the UN Charter—the right to individual or collective self-defense—in the ICoC. However, this element is even further clarified in the text of the current draft treaty. The text of the 2008 draft states, “Nothing in this Treaty may be interpreted as impeding the exercise by the States Parties of their right of self-defense in accordance with Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations.” The text in the current draft treaty takes a step further and adds a reference to collective self-defense in that “This Treaty shall by no means affect the States Parties’ inherent right to individual or collective self-defense, as recognized by Article 51 of the UN Charter.” This inconsistency between railing against the “self-defense” principle of Article 51 mentioned in the ICoC and promoting it within the PPWT brings into question the legitimacy for bringing the current draft forward to coincide with negotiations for the ICoC.

A further interesting aspect of the current draft treaty is the so-called “Executive Committee” outlined in Article VI. The concept of the “Executive Committee” was mentioned in the 2008 draft, but the current draft treaty fleshes out some of the responsibilities of this committee to include operation and implementation of the treaty, addressing alleged violations of the treaty, developing procedures for sharing data and information analysis, and distribution of information collected pursuant to transparency and confidence-building measures. The responsibilities outlined for the Executive Committee begin to bring form to an otherwise amorphous construct but fails to spell out the structure, responsibilities and financial obligations with specific detail if at all.

With regards to dispute resolution, the current draft treaty outlines a graduated methodology in Article VII. However, one notable exclusion from the dispute resolution mechanism in Article VII is the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s new Optional Rules for Arbitration of Disputes Relating to Outer Space Activities (the Rules.) Any dispute involving an enacted PPWT would involve state parties with competing geopolitical interests and would likely revolve around the use of dual-use technology. The availability of the Rules to impartially arbitrate a dispute arising out of an enacted PPWT would be an obvious option as part of any dispute resolution mechanism in order to obtain an impartial resolution. That the Rules are not included as an option in the current draft of the PPWT suggests that either the drafters overlooked the availability of the Rules, or that they are not concerned with impartiality, which again brings into question the motivation of the accord.

| Absent a drastic shift in US space policy, the future legitimacy of the PPWT is questionable, if not terminal. |

Aside from the specific concerns outlined, the current draft, not unlike the original, is nebulous. China and Russia responded to concerns by other states about the vagueness of the original draft by stating that further detail could be fleshed out once states became a party to the treaty. This means that in order to flesh out the detail, a state will have to legally bind itself to the PPWT in its current form before it can read the fine print. That would give Russia and China significant legal influence to back a state into a legal and political corner, all the while enhancing its soft-power base in the UN and, specifically, in the Conference of Disarmament. It is likely that concerns of vagueness with the current draft treaty will be met with the same response from its sponsors: suspicion.

These concerns for the moment are moot because the State Department has all but rejected the draft treaty. This was not a surprise to anyone in the international community and certainly was expected by both of the PPWT's sponsors. The timing of this new draft suggests that, rather than a legitimate effort to move the PPWT forward, it was merely an effort by China and Russia to breathe life into the Conference of Disarmament, preserve their soft-power advantage among third-world nations in the UN, and to take the spotlight off the ICoC and the effort to utilize transparency and confidence-building measures in the Group of Government Experts to address outer space security issues. Whether they succeeded or not remains to be seen, but absent a drastic shift in US space policy, the future legitimacy of the PPWT is questionable, if not terminal.