Deep in space, corner of No and Whereby Dwayne Day

|

| It may influence our music and our movies. Maybe somebody will write an orchestra devoted to Pluto. And based upon past experience, the flyby may affect our entertainment. |

A month from now on July 14, that famous American holiday Bastille Day, New Horizons is going to fly past Pluto and the media is going to explode. You can feel it happening already with the pre-encounter media coverage. New Horizons and Pluto stories have already graced the covers of multiple magazines, often with lazy editors using the exact same image as their competition. A month from now, Pluto will be on dozens of magazine and newspaper covers. The best flyby image is going to be plastered all over the web and the evening news. This mission will almost certainly gather more attention and web traffic than any other NASA robotic space mission, including Curiosity and its “Seven Minutes of Terror.” The mission’s principal investigator, Alan Stern, has stated that there are currently five documentary film crews—three American as well as NHK and BBC—following around his team and producing documentaries. There will probably be extensive coverage on the cable news shows as well.

But beyond the news coverage, how will the Pluto flyby change us?

The Pluto flyby will certainly change our science. We know very little about Kuiper Belt Objects, of which Pluto is the flagship, and everything we know is based upon distant observation. They are nothing but tiny blobs in the lenses of powerful telescopes. Pluto is going to change all of that. Every time a spacecraft encounters a new object in our solar system we are surprised. Every single time. And Pluto is going to surprise us and rewrite our textbooks.

The Pluto flyby will change our culture. Pluto occupies a place in our imagination. For many people it is still the smallest and most distant planet, a lonely little enigma way out there in the black. That is going to change. We don’t know how. Perhaps Pluto will forever after be known not as a mystery, but as a key to understanding the distant regions of our solar system. It may influence our music and our movies. Maybe somebody will write a symphony devoted to Pluto. And based upon past experience, the flyby may affect our entertainment. The 1994 crash of comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 into Jupiter inspired the 1998 movies Deep Impact and Armageddon and dozens of movies, TV shows, and documentaries about the dangers of killer asteroids. The 1997 Mars Pathfinder mission inspired the 2000 movies Mission to Mars and Red Planet. And it is doubtful that Ridley Scott would be currently filming The Martian if the Curiosity rover had not spectacularly set down on Mars in 2012. So maybe a few years from now we’ll have a movie about a human mission to Pluto in addition to all those documentaries currently in production.

A collection of recent magazine covers featuring Pluto and New Horizons. |

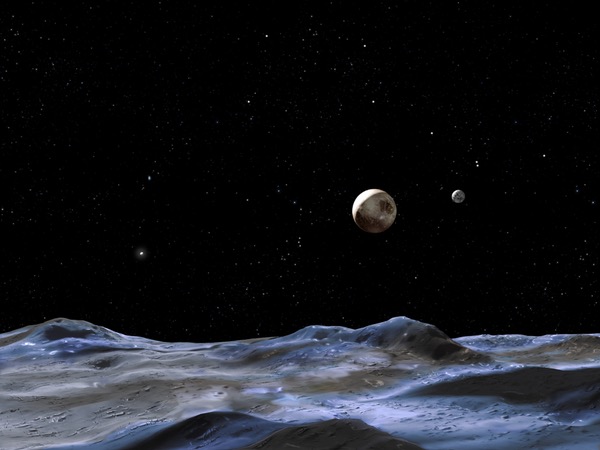

The Pluto flyby will change our art. Look at those magazine covers one last time. Look at the artist depictions of Pluto. That’s probably the last time you’ll see that art, and possibly the last time you’ll see an artist depiction of Pluto in space. After the flyby you will probably only see photographs of Pluto, not paintings. But it may go beyond that. Maybe that tiny cold rock and its moons will light a spark of imagination in some young artist who will produce a sculpture or a poem or something we cannot even imagine.

| The deluge of Pluto science may create a new group of Kuiper Belt Object scientists interested in using Hubble and other telescopes to search for other objects, or even lead to approval of another mission to head out into the Black, way out at the corner of No and Where. |

The Pluto flyby will change our politics. Wars will not end because of a tiny spacecraft flying past a distant object in our solar system. There are over seven billion people on planet Earth, and most of them may not even hear about this event. But some will hear about it, and they will realize that it is an American spacecraft doing this, just as they saw an American rover land on Mars and American spacecraft orbit Jupiter and Saturn. NASA is one of the greatest goodwill ambassadors that the United States has. NASA demonstrates American ingenuity and quality and capability. It is the ultimate example of soft power, convincing other countries that the United States is a country to be admired and befriended. This is not a big thing, not a ratchet of a gear in global power politics. But this flyby, this accomplishment, adds a marker in the plus column for America’s standing in the world.

And finally, the Pluto flyby may change our space policy. Past space mission spectaculars have altered the trajectories of American space policy, and New Horizons flying past Pluto may do so as well. The success of the Curiosity landing may have led to the approval of the Mars 2020 rover. The confirmation of long-suspected water plumes on Enceladus has created a nascent community of scientists interested in mounting a mission to study that small Saturnian moon. The possible discovery of water plumes on Europa may have tipped the scales in favor of starting a mission to visit that ice world. The deluge of Pluto science may create a new group of Kuiper Belt Object scientists interested in using Hubble and other telescopes to search for other objects, or even lead to approval of another mission to head out into the Black, way out at the corner of No and Where.

It is unlikely that these changes to our science, art, culture, politics, and policy will be profound, but who knows? There have been numerous times throughout history where space objects have had significant effects on human lives: the appearance of Halley’s comet was often interpreted as a sign of impending doom, and the alleged discovery of canals on Mars led to stories about alien cultures and alien invasions. The landing of humans on the Moon created an expectation of greatness that our space program and our country has not always achieved. So there is precedent.

Pluto will change us, we just don’t know how.