Future’s Past: The astronauts of 2001: A Space Odysseyby Dwayne Day

|

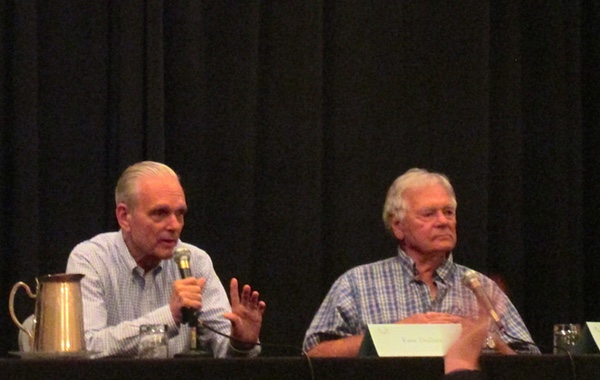

| Both actors really liked working for Stanley Kubrick. They thought that he was polite, never yelled, was highly prepared, and was a collaborative director. |

In 2014, the art book publisher Taschen released an expensive collectible book set devoted to 2001, and in recent months the publisher produced a more affordable version of one of the books. Another book on the art design of 2001 is due out soon, joining a long line of books about the making of this monumental film. Not bad for a movie that was frequently panned by critics when it first debuted in 1968. 2001: A Space Odyssey still captures the imagination.

The East Coast’s geek party Dragon Con occurs in Atlanta every Labor Day weekend, attracting tens of thousands of people. Dragon Con’s focus leans toward fantasy (particularly urban fantasy), which doesn’t interest me, but also includes science fiction, which does. One of Dragon Con’s attributes is that many of its guest speakers appear multiple times, so you have numerous opportunities to see them them over the extended four-day convention. Two of the guests at the most recent Dragon Con were actors Keir Dullea (pronounced “duelay”) and Gary Lockwood, who played astronauts Dave Bowman and Frank Poole in 2001. The two men, now in their late seventies, told a number of interesting stories about working on the movie and clearly viewed it as one of the highlights of their careers. Certainly it is the experience that they are both asked to speak about most regularly.

Both actors really liked working for Stanley Kubrick. They thought that he was polite, never yelled, was highly prepared, and was a collaborative director. They also considered him a genius. Dullea had been impressed with Kubrick’s 1956 movie The Killing, and after seeing it in a theater he had specifically sought out the movie poster to learn who had directed that film. But Kubrick had not rocketed to fame until 1960 when he directed Spartacus, a film that gave Kubrick serious clout in Hollywood but also convinced him that he needed total control of his projects. Lockwood was also a Kubrick fan and became all the more convinced of his genius upon seeing the sets and production design for 2001. Dullea said that he had been a science fiction fan since his youth and when he first read the script for 2001 he immediately recognized its origins in Arthur C. Clarke’s 1951 short story “The Sentinel,” which he had read as a teenager.

Dullea and Lockwood at Dragon Con. (credit: D. Day) |

Neither actor auditioned for their roles: they were simply offered them based upon their previous work. Dullea said that the best directors are very good at casting actors who don’t require directing. This drew a chuckle from the audience, but Dullea explained that a good director picks exactly who he wants based upon a careful assessment of their abilities, and then doesn’t have to tell them what to do.

Both men told stories about their collaboration. For instance, at the end of the movie when Dullea’s character is an old man, there is a series of transitions where he looks to see his older self. Dullea suggested that instead of his character simply looking over at the bed, they needed something to cause him to look in that direction. That’s where they came up with the idea of knocking the glass off the table and when he looks at it, he turns toward his oldest self on his deathbed.

| Lockwood also said that they got to meet the Apollo 11 crew, and then he paused and said, “I liked Neil… I don’t like Buzz.” |

Lockwood told a story about how he had a difference of opinion with Kubrick about a scene. Shortly after shooting had ended for the day, one of the stagehands told him that Stanley wanted to see him in his apartment. Lockwood said he thought to himself, “Well, I’m going to get fired.” He walked over and knocked on the door and Stanley Kubrick let him in. Surprisingly, Kubrick said to him, “I heard you’re a Chopin fan. I have a new album you should hear,” and he went over to a wall of albums and started to retrieve one. Lockwood was a little surprised but said, “Before we listen, let’s cut to the chase. Am I fired or not?” Kubrick replied no, he wasn’t firing him because of their dispute about the scene. He said that he had learned over the years that actors have knowledge and insights that directors don’t, so he was willing to hear what Lockwood thought. It was a sign of Kubrick’s skills as a director that he did not let his ego prevent him from listening to his actors.

The actors also talked about the film’s lack of dialogue. They said that when they got hired for the movie they were given dossiers on their characters that explained their backgrounds. Astronauts Poole and Bowman were supposed to be super smart, with lots of academic degrees and experience. But they were also on a mission that had been underway for over a hundred days. So when the film picks up with them in space, the two astronauts have been living together for months and pretty much said everything they’re going to say to each other unless it was work-related. They’re all talked out by that point, which is why they say almost nothing during the scenes on the Discovery.

Dullea explained that he had a really technical and jargon-filled bit of dialogue to memorize. It was when the astronauts report the failure of the electronics unit to mission control. Dullea was really worried about it, so he studied it again and again, driving himself nuts. Then he delivered it flawlessly on camera. In the end, it is nearly identical to the language used by mission control reporting back to Discovery, saying that they agree with his assessment of the problem, so Kubrick cut Dullea’s scene. But Dullea said that he still remembers it perfectly, nearly fifty years later. And then he delivered the very long bit of jargon-laden dialogue and got a laugh and applause from the audience.

Lockwood also said that they got to meet the Apollo 11 crew, and then he paused and said, “I liked Neil… I don’t like Buzz.” He added that often when he and Dullea do joint appearances at film showings, somehow Buzz Aldrin always seems to appear and people want to introduce Aldrin to him. Lockwood drolly replies that he already knows the moonwalker. He implied that he had a similar low opinion of William Shatner, with whom he appeared in the second television pilot for Star Trek.

Lockwood also told a great story about working on the centrifuge set, which he thought was brilliantly designed. He joked that he realized that Kubrick hired him for the job because of his previous experience as a cowboy stuntman. One day Lockwood found himself strapped into his chair, eating goop from his food tray—upside down. Keir Dullea was supposed to climb down the ladder at the center of the set and then the whole set would rotate as he walked over to where Lockwood was sitting. Kubrick called “action” and told Lockwood to take a bite, and Lockwood then watched as the three squares of goop slowly peeled off his tray... and fell nearly 70 feet to the floor below, splattering everything on the pristine white set. They didn't shoot for the rest of the day.

The actors took some questions from the audience and had some really interesting answers. For instance, somebody asked if they knew that the film would be a classic. Dullea said that he had his doubts because the early reviews were so poor. In particular, he mentioned New Yorker film critic Pauline Kael’s infamous devastating review, where she referred to 2001 as “trash masquerading as art” and “monumentally unimaginative.” Kael later recanted upon seeing the film a second time, but 2001 received numerous other lackluster and even harsh reviews. Considering that 2001 was released way behind schedule and over budget, expectations had been high, and presumably many critics were waiting to pounce.

| An audience member asked if either actor would change anything about their performances. Dullea said no, that he thought that his performance was perfect and the film was perfect. |

In contrast, Lockwood replied that he never had any doubts. He said that he had a lot of faith in Kubrick and when he looked around at the sets and he read the script he was so impressed that he knew they were making something that would be remembered forever. In fact, he recounted how they had premiered the movie in one city and it had gotten a mixed reaction in the theater. They then flew to another city for the premiere and Lockwood was sitting next to Arthur C. Clarke, who was in a gloomy mood. Lockwood told Clarke that he was incredibly lucky, because it was only then, at that precise moment in time, that a director as skilled as Kubrick, and the technology to realistically depict spaceflight, both existed to take Clarke’s story and turn it into something amazing.

Dullea and Lockwood have done many joint appearances over the years, but one question from the audience prompted a response from Dullea that surprised Lockwood. An audience member asked if either actor would change anything about their performances. Dullea said no, that he thought that his performance was perfect and the film was perfect. Lockwood seemed genuinely surprised that he had never heard Dullea say that before, and said he agreed with him: he wouldn’t change a thing.

There was an awkward moment during their talk. At one point a woman stood up and said that she teaches a Girl Scout troop about space and she uses 2001: A Space Odyssey to show the class a fictional but realistic depiction of spaceflight. But she added that the girls don’t like the movie. Considering that 2001 was widely regarded as slow and confusing even 47 years ago, the fact that today’s teenagers might have a difficult time with the film is unsurprising.

But Lockwood interpreted the comment in an entirely different way. He replied that in all his years of signing autographs and giving talks about the movie, most of his audience has been male. “Guys are gearheads,” he said, and like the movie because of its technology and hard science fiction storytelling. He said that he has not encountered a lot of women—he referred to them as “ladies”—who like the movie. He added that when he talks to his friends’ wives their eyes glaze over at mention of 2001.

This prompted one woman in the back of the audience to loudly yell out “I grew up as a fan of Star Trek and Star Wars and that’s horseshit!” These days somebody is always outraged about something, but usually they vent their anger on the Internet; rarely do they consider it socially acceptable to yell expletives at the guests on a stage. This woman, however, was clearly incensed, equating her personal experience as a fan of science fiction as proof that Lockwood’s observation about 2001’s fanbase was wrong, and sexist.

Lockwood didn’t hear the entire shouted objection, but it prompted a bit of back and forth between Lockwood, who seemed somewhat mystified (he had not said that women were uninterested in science fiction, only in 2001), and some in the audience. Another woman in the audience yelled, “Saying that girls don’t like science fiction is what prevents girls from saying that they like science fiction.” Dullea said that he could see logic in that argument and the situation was quickly defused, although it wouldn’t surprise me if the first angry woman tried to corner Lockwood later and give him a piece of her mind, expletives included.

At that point I looked around the audience. The session started at 5:30 on a Saturday and ran past 6:30 pm, which is about the time that the endless Dragon Con parties begin, so the room was not packed. Plus, this was the second time the actors had discussed the film that weekend. There were probably 200 people in the room, and probably only ten percent of them were female, essentially validating Lockwood’s observation about the movie’s fans.

Despite the little bit of controversy, it was great to hear Dullea and Lockwood discuss their experiences shooting a film that, almost a half century later, remains perhaps the greatest example of science fiction filmmaking ever produced.