Accelerating the next, next space telescopeby Jeff Foust

|

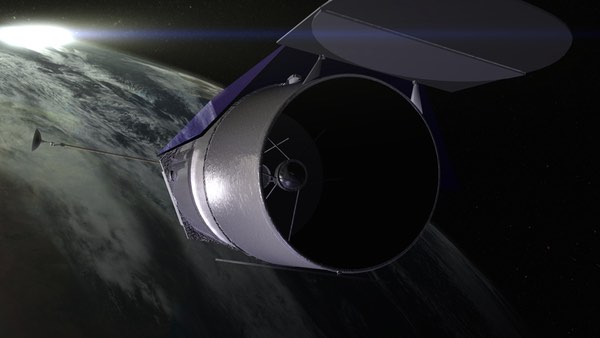

| NASA officials announced last week that WFIRST will “enter formulation” in February. “That’s the official start of the project,” said Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division. |

The assembly of JWST’s primary mirror is just one aspect of the telescope’s construction. Elsewhere, the telescope’s instruments are being tested while the spacecraft bus and its deployable sunshade, the size of a tennis court, are put together. Several years after a critical “replan” of the observatory, years behind its original schedule and billions of dollars over its original budget, NASA says JWST remains on track for launch on an Ariane 5 in October 2018.

That means that spending on JWST—$620 million for the 2016 fiscal year—will soon ramp down. For several years, NASA had been anticipating the “wedge” in the budget this would create and started planning for the next large space observatory beyond JWST that wedge of funding would enable. The leading candidate for that mission has been a concept called the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope (WFIRST), one endorsed by astronomers as their top priority large mission in their latest decadal survey in 2010.

WFIRST, as it turns out, will start even sooner that NASA expected. At the 227th Meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) held last week in Florida, agency officials announced that WFIRST will “enter formulation” in February. That milestone, also known in NASA’s project management terminology as “Key Decision Point A,” sets WFIRST on course for a launch in the mid-2020s.

“That’s the official start of the project,” Paul Hertz, director of NASA’s astrophysics division, said of that WFIRST milestone in a presentation at the conference January 4.

As recently as last year, NASA didn’t expect a formal start for WFIRST until next year. In its fiscal year 2016 budget submission, which requested $14 million for WFIRST pre-project studies, NASA said that would “enable the potential start of Phase A formulation activities no earlier than FY 2017.”

Congress, though, had different ideas. The omnibus spending bill approved by Congress last month provided $90 million for WFIRST. It also adopted language in the report accompanying a Senate spending bill in June calling on NASA to accelerate the start of the mission.

“The Committee has accelerated this key mission recommended by the decadal survey and expects it to achieve overlap and scientific synergy with Hubble and the James Webb Space Telescope, including linking science operations and the science archive,” the June report from the Senate Appropriations Committee stated. At the time, the Senate asked NASA to start formulation no later than January 15, a deadline the agency will miss by about a month.

This wasn’t the first time Congress provided additional funding for WFIRST. In 2015, NASA also requested $14 million for studies to support the space telescope, only to have Congress allocate $50 million. A year earlier, Congress appropriated $56 million for WFIRST.

| “We’ve gotten very good funding the last few years. It has allowed us to address the technology issues up front,” said Gehrels. |

That nearly $200 million over the last three years has served as a down payment of sorts for a mission whose total cost NASA currently estimates at between $2 billion and $2.3 billion. (A formal cost and schedule estimate will come at a later project milestone, Key Decision Point C.) A schedule presented at a meeting a National Academies committee in October showed WFIRST reaching that Key Decision Point C in late 2018, with a launch readiness date of August 2024.

Much of that funding has, so far, gone towards initial studies of WFIRST’s two key instruments: a wide-field infrared camera and a coronagraph that can block light from stars to enable direct detection of planets orbiting them. Those instruments will be used for studies ranging from the characterization of exoplanets to the nature of dark energy.

“The technology development for WFIRST is going well,” Hertz said, adding that various reviews have recommended that NASA emphasize technology maturation early in the mission’s division. “That’s a lesson we’ve learned from lots of different missions.”

“Some years ago, we laid out a set of milestones in the technology development necessary for both the wide-field detector technology and the coronagraph technology,” he said. “We have made every one of our milestones on schedule so far. That doesn’t mean that we’re in the clear, but it means the team is working really hard, and that they have an implementable plan, not a wishful thinking plan.”

One of the scientists involved with WFIRST also endorsed this approach. “We’ve gotten very good funding the last few years. It has allowed us to address the technology issues up front,” said Neil Gehrels, the WFIRST study scientist at NASA Goddard, at a town hall meeting about the mission January 5 during the AAS meeting.

“This is really a good way to do a big mission like this,” he continued. “We can lower the risks and figure out the technologies before we get a large army developing the mission.”

Beyond the general description of the instruments, the other key aspect of WFIRST is the use of a spare 2.4-meter telescope officially known as the Astrophysics Focused Telescope Asset (AFTA). That telescope is one of two donated to NASA in 2012 by the National Reconnaissance Office, although the agency is sometimes hesitant to identify the source: Hertz, in his AAS presentation, noted the AFTA telescope was one “that we obtained from another government agency.”

The use of the AFTA telescope, larger than the 1.3-meter one previously planned for WFIRST, enables more science. “It’s a beautiful, Hubble-quality telescope, so it gives us Hubble-quality imaging,” Gehrels said. The larger telescope, he said, also allowed the addition of the coronagraph to support the booming field of exoplanet science.

As currently planned, WFIRST will launch on a large EELV-class rocket—a Delta IV Heavy is mentioned in the October presentation, although the formal selection of a launch vehicle is still years away—and operate from the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point, the same one that will be used by JWST. (That is also a recent change: earlier WFIRST concepts had it operating in geosynchronous Earth orbit.) The telescope will have a prime mission of at least six years.

The specifics of what WFIRST needs to do to meet the goals of astronomers will be shaped by science investigation teams NASA announced in December. “This is the team that will be helping us set the requirements that will guide the final design of the WFIRST observatory,” Hertz said.

| “We will be needing to make adjustments across the rest of the astrophysics portfolio to realize a savings of $36 million relative to our planned numbers,” Hertz said. |

The gift of additional funding from Congress to speed up WFIRST—similar to Congressional efforts to accelerate work on a mission to Jupiter’s moon Europa—does come at a cost elsewhere in the agency’s budget. While Congress provided $76 million more than requested for WFIRST, the overall increase for the agency’s astrophysics program was only about $40 million.

With funding for JWST protected, as well as money for both Hubble and the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, the rest of NASA astrophysics is thus facing $36 million in cuts compared to the agency’s original request of nearly $500 million for those programs 2016. “We will be needing to make adjustments across the rest of the astrophysics portfolio to realize a savings of $36 million relative to our planned numbers,” Hertz said.

Hertz didn’t disclose what those specific cuts would be, since NASA has not yet formally submitted an operating plan to Congress with the details of those and other adjustments. He said those details should be available in about a month, when the operating plan is submitted.

Of concern to some astronomers is the effect the cuts will have on operating missions. NASA is in the process of a “senior review” of astrophysics missions that are beyond their primary mission. Six missions are up for review: Fermi, Kepler, NuSTAR, Spitzer, Swift, and NASA’s participation in ESA’s XMM-Newton. Proposals for extended missions for those six are due this month, with decisions from NASA due in the spring.

Could the past be sacrificed for the future? That won’t be known for months, depending on the outcome of the senior review and the agency’s operating plan. However, the future of space astronomy—both the telescope whose mirrors are being installed at Goddard, and the one about to become a formal project—is at least on schedule again.