Desolate magnificenceby Dwayne Day

|

LRO images on display. (credit: D. Day) |

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, or LRO, was launched in 2009 and has been chugging away ever since. If nothing breaks, in four or five years the spacecraft will probably run out of fuel and, because the Moon’s gravity field is uneven, it will ultimately fall and silently crash into the surface after more than a decade in orbit.

| The museum’s photographs reveal that many of the images also border on art, showing subtle variations of grays that can be oddly pleasant to the eye while simultaneously cold, even scary. |

LRO is a bit of an oddball project. It was actually approved and paid for as the first step in the Bush administration’s Vision for Space Exploration. The plan was to return Americans to the lunar surface, and program planners determined that the first thing they needed was high-resolution imagery of potential landing sites. In an example of effective cooperation within NASA, the human spaceflight and science parts of the agency got together and developed a suite of instruments to provide their highest priority data. Such cooperation sometimes falters early as one side or the other finds the terms not to their liking, but it worked well in the case of LRO, and after an initial phase devoted to and paid for by the human spaceflight side of NASA, LRO became entirely science-driven. In the meantime, a new presidential administration had lost interest in the Moon, and LRO was no longer necessary for NASA’s human spaceflight mission. But from a scientific standpoint the spacecraft was still productive, and it has helped to enhance and change our understanding of the Moon.

LRO image on display. (credit: D. Day) |

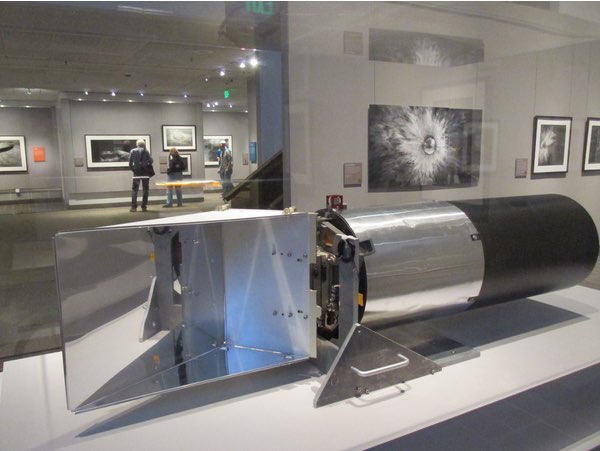

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera, or LROC, was designed to produce high resolution images of the surface, necessary for selecting landing sites, but also valuable from a scientific standpoint. Until LRO, most of the Moon’s surface had been photographed only at low resolution, with some at medium resolution. LRO has now photographed most of the Moon at medium resolution and significant portions at high resolution, beaming back many terabytes of data. The museum’s photographs reveal that many of the images also border on art, showing subtle variations of grays that can be oddly pleasant to the eye while simultaneously cold, even scary. It is possible to look at some of these images and almost be transported to the surface and shiver at what Buzz Aldrin famously called the Moon’s “magnificent desolation.”

What the exhibit demonstrates is that the Moon still has mysteries both big and small. Take, for example, the lunar swirls—bright flowing patterns on the surface that almost look as if they have been airbrushed over the geography, over the flat surfaces and the peaks. Scientists don’t know what causes them, but one theory is that the remnants of the Moon’s magnetic field, still trapped under parts of its surface, affect the way the solar wind blows down on the Moon and darkens or lightens the material on top. Trying to wrap your mind around that, comprehending invisible forces and eons of time etching subtle patterns on the surface of the Moon is a difficult challenge. You have to expand your way of thinking and your sense of time and scale.

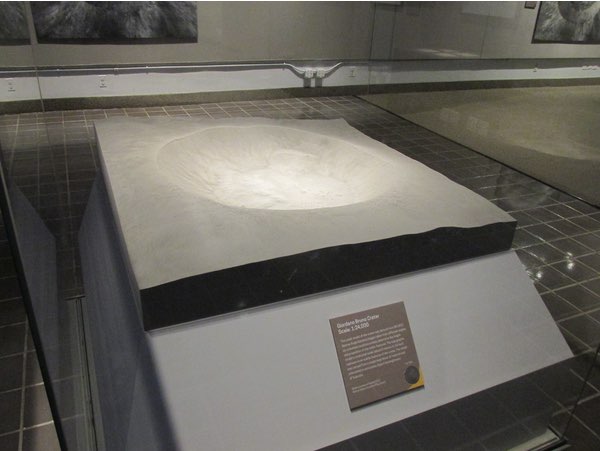

A relief model of Giordano Bruno Crater derived from LRO data. (credit: D. Day) |

LRO imagery also reveals intriguing aspects of the Moon that are easier to understand. For instance, the exhibit shows the collapsed lava tubes that expose entrances to subsurface caves, and channels carved into the surface by ancient flowing lava. Scientists looking at LROC data have also found more than sixty examples of much more recent lava activity, perhaps only 10 to 100 million years old, a mere blink of an eye in geological time.

| What the exhibit demonstrates is that the Moon still has mysteries both big and small. |

The exhibit features a number of spectacular photographs of craters, including enigmatic Tycho, which has a big central peak that may have formed when the compressed floor rebounded after the impact that formed it. On top of the peak is a boulder more than a hundred meters long. Scientists are unsure how that bolder got there. Did it fall back after the impact? And if so, how come it didn’t shatter? As most space geeks know, in the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey the crater is the site of the Tycho Magnetic Anomaly-1, which is revealed to be a monolith of extraterrestrial origin. Maybe aliens left the boulder on the peak just to mess with us.

The exhibit indicates that one of the ways that LRO data has been useful is providing context for scientific data collected at various landing sites. For instance, LROC imagery and data of some of the Apollo sites has indicated where lunar samples collected by Apollo astronauts may have originated elsewhere before ending up at the landing site and in an astronaut’s rock sample bag. In at least one case, the LRO data has demonstrated that samples thought to be from one geological feature were actually part of another one that the astronauts did not realize they were sampling, like picking up a rock on a beach and thinking it had been brought there by the ocean rather than a landslide.

A model of the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera on display at the museum. (credit: D. Day) |

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter’s images have also captured the Apollo hardware left on the Moon, as well as the Soviet Lunokhod rovers and other hardware. The spacecraft has even taken images of the most recent lunar visitor, China’s impressive Chang’e-3 lander and Yutu rover.

Eventually, not too many years from now, LRO is going to impact the Moon. When it does so it will leave a crater, and perhaps someday a future orbiter will sail overhead and image it. Maybe that photo will also end up in the Smithsonian. Or maybe, just maybe, some future explorer will walk the surface of the Moon to the site of the impact and bring back a piece of the camera that has produced such amazing photos of Earth’s closest neighbor.