A launch company, and industry, in transformationby Jeff Foust

|

| “This engine is giving us a price 60 percent of the AR1,” Tobey said of the BE-4. |

Such a discussion might have made sense in a more private setting, but not in an event publicized on campus in advance for anyone interested in attending. A recording of the seminar, circulated via YouTube, Facebook, and Reddit, was the talk of the space industry in less than 24 hours. ULA quickly distanced itself from his comments and, by late March 16, Tobey had resigned.

Much of the uproar focused on just a few comments. Tobey likened the competition between Aerojet and Blue Origin to provide a first stage engine for ULA’s new Vulcan vehicle to having two fiancées, one he acknowledged up front was a “bad analogy” but which he pursued nonetheless.

“So we’re sitting here as a groom with two possible brides, we’ve got Blue Origin over here, the super rich girl, and we’ve got this poor girl over here, Aerojet Rocketdyne,” he said. “We’re doing all this work for both of them, and the chances of Aerojet Rocketdyne coming in and beating the billionaire is pretty low.”

Worse, perhaps, was the suggestion that ULA did not bid on a GPS launch contract last fall—the first competition for an Air Force mission that pitted ULA against SpaceX—primarily because of cost. “The government was not happy with us not bidding that contract because they had felt that they’d bent over backwards to lean the field in our advantage, but we even said we no-bid, because we saw it as a cost shootout between us and SpaceX,” he said.

Lost in the discussion in the days after his comments became public, though, were some interesting items about ULA’s vehicle development efforts and the company’s self-described “transformation” to lower its costs without sacrificing reliability or performance.

Some of that involved that competition between Aerojet Rocketdyne’s AR1 engine and Blue Origin’s BE-4. ULA’s interest in the BE-4 took many in the industry by surprise when it was announced in 2014: Blue Origin is a new entrant into the industry that hasn’t built an engine the size of the BE-4, and chose a different propellant mix— liquefied natural gas and liquid oxygen—for its engine. Aerojet Rocketdyne, meanwhile, has decades of experience with engines of all sizes, and its AR-1 uses the same kerosene (specifically, RP-1) and liquid oxygen that powers the Russian-built RD-180 engine in the Atlas V.

So why take a chance with an untried company and engine design? Tobey suggested a big factor is cost. “This engine [BE-4] is giving us a price 60 percent of the AR1,” he said. Blue Origin is also self-funding the development of the engine, rather than seeking Air Force development contracts as Aerojet has. “Jeff Bezos has committed over a half billion dollars to the development of this engine,” he said. (Bezos, in a media tour of Blue Origin’s headquarters last month, declined to say how much he had spent on the company in general, let alone specific efforts like the BE-4, but suggested his overall investment in the company to date exceeds $500 million.)

While BE-4 might be the favored engine of ULA currently, as both Blue Origin and ULA officials have publicly suggested, Tobey revealed its development has not been without problems, including an explosion during a test of the engine’s “powerpack” on a test stand, but that Bezos quickly moved ahead. “So he blew up this powerpack, but then he just opened up his checkbook and said, okay, we need to rebuild our test stand that we just blew up,” Tobey said.

| “It’s taking and rebalancing the workforce so that there’s a mixture of lower labor grades as well as senior labor grades in the workforce,” Tobey said, “and just a lot of chaos, if you will, going forward.” |

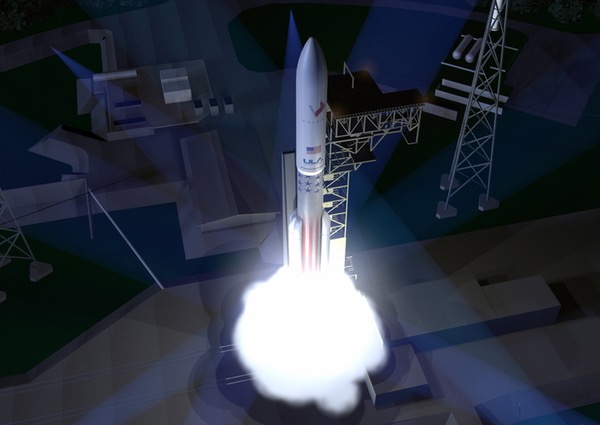

The selection of a first stage engine is just one part of the overall development of Vulcan, at the core of ULA’s efforts to transform itself to respond to a changing, and more competitive, launch market. “Vulcan is basically our way to redesign a booster,” he said. “We’re designing a new booster that has the same performance as the Atlas, but we’re trying to do it for about a third of the cost.”

Tobey also provided some foreshadowing of changes at ULA. “So what we have to do, and what I was hired to do last summer, was to take and lead this transformation of ULA’s engineering workforce from where it was and into the future,” he said. That includes a “reshaping” of the workforce. “It’s taking and rebalancing the workforce so that there’s a mixture of lower labor grades as well as senior labor grades in the workforce, and just a lot of chaos, if you will, going forward.”

Earlier this month, ULA acknowledged that it plans to cut 375 jobs this year, followed by 400 to 500 more in 2017, at a company that currently employs about 3,400 people.

Aerojet Rocketdyne president and CEO Eileen Drake discusses her company’s development of the AR1 engine during a launch panel at the Space Symposium April 14 as ULA president and CEO Tory Bruno (left) listens. (credit: Space Foundation) |

Heavy-lift panel

The opposite of off-the-cuff remarks at a university seminar is, perhaps, a large panel session at Space Symposium, one of the space industry’s biggest annual conferences. The launch “Mega-Session” on the afternoon of April 14 certainly was mega: ten panelists, representing a range of companies in the industry. With a large panel, and only 90 minutes, there wouldn’t be much opportunity for speakers to step out of bounds, particularly with prepared remarks (accompanied, in most cases, by videos) by each speaker taking up the bulk of the time.

While no individual speaker made much news, there was still an opportunity for speakers, if not clash with one other, at least offering contrasting viewpoints on some topics. That included, not surprisingly, the issue of what engine ULA should choose for Vulcan.

Eileen Drake, president and CEO of Aerojet Rocketdyne, made a strong pitch for the AR1. “I’m very proud to be a part of Aerojet Rocketdyne, a company that is the only company that has developed and produced very large booster engines,” she said. A recent award from the Air Force to support AR1 work “speaks volumes for the confidence that the national security community has in the AR1 and Aerojet Rocketdyne.”

She added that the company specifically a “very proven propellant” along with an engine design to minimize risk, a subtle criticism of Blue Origin’s use of liquefied natural gas. “We believe that the AR1 engine is the fastest path, lowest cost, lowest risk to the taxpayer to ending our reliance on the RD-180,” she said, suggesting later the AR1 could be used not just on Vulcan, but also on the Atlas itself.

Rob Meyerson, president of Blue Origin, made a case for the BE-4 later in the same panel. “The BE-4 engine is America’s new engine that will replace the RD-180,” he said, enumerating the reasons why the BE-4 is the preferred choice, from a head start on development and engine performance to access to dedicated test facilities and a “rapid decision-making process.”

| “Heavy lift will never be a commodity until there’s a fundamentally different way of going to space,” Bruno said. |

Meyerson said that “significant testing” of the BE-4 is underway, leading up to full-scale engine tests in the fourth quarter of this year. “We look to delivering the first BE-4 engine for both the Vulcan Centaur vehicle and Blue Origin’s own orbital launch vehicle by the end of this decade,” he said.

Tory Bruno, the president and CEO of ULA, didn’t weigh in on the engine debate on the panel, but he did trigger another debate, on the issue of mission assurance and risk management for launches. Bruno argued that he expected commercial launches to move more towards the national security model of mission assurance, one that is typically considered to be more comprehensive, but also more expensive.

“There is nothing that is done in the national security space model that is not applicable to commercial,” he said. “As traditional providers like ourselves enter that marketplace, we are going to bring those techniques and those disciplines to that market, and make commercial lift every bit as reliable.”

Another panelist took a different view. “I’m not sure that, for us, there’s a choice,” said Claw Mowry of Arianespace. He noted that the company launched primarily commercial satellites, but also national security missions for European governments, using the same processes for both. “It’s been successful for us: Ariane 5 has been successful more than 70 flights in a row, and we have the lowest insurance rates in the business.”

Bruno, later in the panel, also questioned whether launch could be “commoditized” as other panelists suggested. “Commodities are tires, commodities are cars, commodities are items like that,” he said. “None of those involve a million pounds of high explosive in a circumstance where years of work, and hundreds of millions of dollars of investment, can disappear in a fiery ball in less than ten seconds.”

“Heavy lift will never be a commodity until there’s a fundamentally different way of going to space,” he added.

SpaceX president Gwynne Shotwell disagreed. “If we say we can’t do it, so we won’t do it, I think that’s a mistake,” she said. Rocket launches today are a “significant emotional event,” she acknowledged, “but I really look forward to the time when it’s not that.”

That would be a transformation that goes beyond a company or even an industry to perhaps society in general.