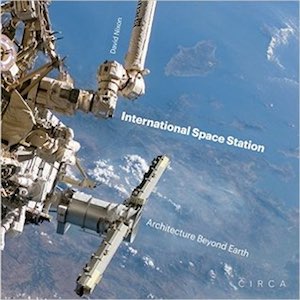

Review: International Space Station: Architecture Beyond Earthby Jeff Foust

|

| Early design concepts in the late 1970s and early 1980s included one by Hughes that would have used four shuttle external tanks, extending from a central core like spokes that rotated to provide artificial gravity, with a ring of solar panels forming a rim. |

That’s certainly the argument of International Space Station: Architecture Beyond Earth, a British book by David Nixon that likens the International Space Station (ISS) to some of the great architectural accomplishments on Earth. The ISS, like buildings and other structures on Earth, exhibits the same three basic design principles dating back to Roman times: strength, value, and style. The ISS has strength, of course, to survive the space environment, and its value comes from its promise to extend human knowledge. And style? The ISS, Nixon writes, “is, without doubt, a very stylish design.” (Russia’s Mir space station apparently was not, by comparison, but Nixon doesn’t offer much of an explanation why.)

Much of the book is not so much an architectural critique of the ISS but rather a history of its design and development. Nixon walks the reader through the long history of the station’s development, starting with early design concepts in the late 1970s and early 1980s. At that time, there was a diversity of ideas, including one proposed by Hughes that would have used four shuttle external tanks, extending from a central core like spokes that rotated to provide artificial gravity, with a ring of solar panels forming a rim. That design did not go anywhere, but for decades afterwards space advocates dreamed of turning external tanks into giant space stations.

What did emerge was an evolving series of designs for Space Station Freedom, from the “Power Tower” to the “Dual Keel” designs that morphed based on both technical requirements and budget issues. The fall of the Soviet Union and a change in administrations in the US provided an opening to bring in Russia to the program just as Freedom was facing its strongest budget fights in Congress. Nixon follows the evolving design, from a technical and programmatic aspect, though the completion of the station’s assembly (more or less: there are still additional Russian modules slated for launch in the next few years) in 2011.

Nixon’s analysis does have a few, mostly minor, flaws. In a section on a 1991 restructuring of the station, he writes about concerns about the shuttle’s flight rate needed to carry it out since “the most missions the Shuttle had flown in a single year so far were three in 1989.” The shuttle, of course, had flown more than that in a calendar year, including nine in 1985.

Towards the end of the book, Nixon declares that the ISS “is a perfect platform for Earth observation.” While the ISS has found considerable interest for Earth observation applications, it’s certainly not a “perfect” platform for it. From its inclination, it can see much of the Earth, including most of the populated regions, but it can’t observe higher latitudes, and unlike spacecraft in a sun-synchronous orbit doesn’t pass over regions at the same local time. It’s a useful platform primarily because it provides much of the infrastructure—power, data, attitude control—that would ordinarily require a separate satellite, lowering costs for instrument developers willing to forego the global coverage or other attributes they might get from a satellite in a conventional sun-synchronous orbit. Useful, but not perfect.

The book makes clear that the ISS is, indeed, an architectural accomplishment. But the book doesn’t delve much into that question of style that he argues is a core design principle. “The way it sparkles in the sunlight from a distance gives it the appearance of an enormous jewel,” Nixon writes. “If we could visit it and touch it, we would be awed and transfixed.” Beyond that, though, the “style” of the ISS is assumed.

| “The way it sparkles in the sunlight from a distance gives it the appearance of an enormous jewel,” Nixon writes. “If we could visit it and touch it, we would be awed and transfixed.” |

But how important is style for a facility like a space station? Mir apparently lacked that style, but was still an effective station for many years; its flaws in later years had more to do with limited budgets and lack of maintenance than a lack of style. Would a future commercial space station—say, a couple Bigelow Aerospace B330 modules connected by a node and with solar arrays sprouting from their sides—be stylish, and if not, is that important for would-be customers?

Maybe not. One of the examples of “great works of architecture” he cites in the book’s foreword is Dulles International Airport outside of Washington, DC. But travelers don’t go to Dulles for the architecture; instead, they go because that’s where they have to fly into or out of, and they ignore the graceful appearance of the main terminal building as they wait in security or customs lines. Most would probably be willing to replace that building with something far uglier if it promised a more streamlined approach to getting onto and off of jetliners. Perhaps the same will be true of space stations, one day.