A taste of Armageddon (part 1)by Charles Vick and Dwayne Day

|

| American intelligence assets kept a focus on Soviet space activities, and American intelligence analysts pieced together multiple sources of information to discern what the Soviets were up to. One source of information was the locations and movements of Soviet space tracking ships. |

By early 1969 a big part of the Moon race was won. Apollo 8 had circled the Moon, beating the Soviet Union there. Based upon their access to top secret intelligence reports, senior NASA leaders knew that the Soviet effort to land cosmonauts on the Moon was also significantly behind the United States. (See: “Dagger of the mind”, The Space Review, December 19, 2016) American reconnaissance satellites had spotted what intelligence analysts believed to be the large Soviet Moon launcher, which the CIA had designated the “J vehicle,”—or, more colloquially, “the J bird”—at its launch pad at Baikonur, which the US intelligence community then referred to as “Tyuratam.” But it had not launched by the time that Apollo 8 had carried astronauts around the Moon. The Soviets had also failed to make their Zond circumlunar program operational, although American intelligence analysts suspected that the Soviets would keep trying. The only way that the Soviets could now beat NASA to a Moon landing was if NASA stumbled badly, perhaps by losing a mission and a crew, and if the Soviets ran a flawless program.

American intelligence assets kept a focus on Soviet space activities, and American intelligence analysts pieced together multiple sources of information to discern what the Soviets were up to. One source of information was the locations and movements of Soviet space tracking ships. American intelligence analysts learned that if Soviet tracking ships headed to sea, that usually meant a launch was imminent. If they went to certain locations, that indicated the type of launch that would occur. Also important was the location of spacecraft recovery ships. Soviet manned spacecraft had all come down on the Soviet landmass. But the circumlunar Zond spacecraft that were intended to eventually carry cosmonauts had come down at sea. Thus, American intelligence analysts concluded if a lunar launch window was approaching, and the appropriate tracking and recovery ships put to sea, a flight to the Moon was likely.

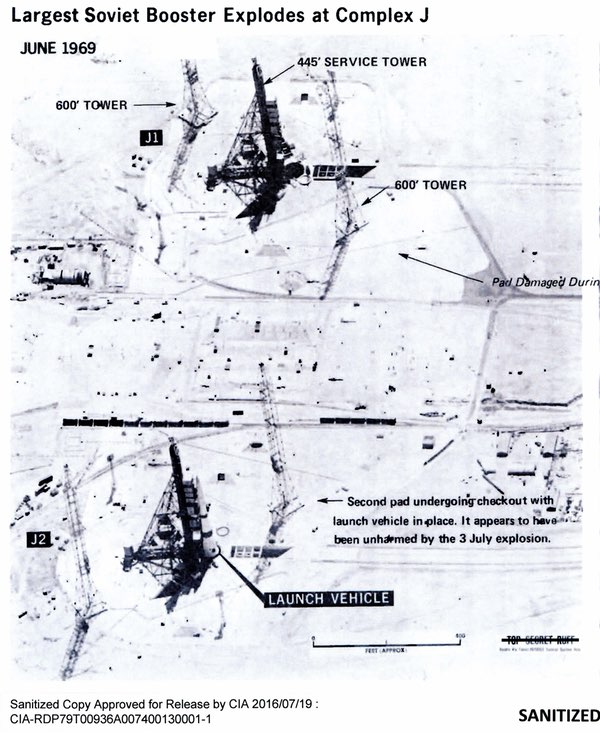

The two N-1 launch pads photographed by an American KH-8 GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellite in June 1969. On February 19, 1969, a Proton launch carrying a Lunokhod rover had ended in failure, and an N-1 launch two days later also failed. At the time, the U.S. intelligence community referred to Baikonur as “Tyuratam,” and the N-1 as “the J-vehicle.” |

On January 20, 1969, the Soviets had launched a Zond circumlunar mission atop a Proton rocket from Tyuratam (a rocket that the US intelligence community designated SL-12). That flight had failed shortly before reaching orbit. But Soviet tracking and recovery forces had performed in noticeable ways for the launch.

A February 6 National Security Agency “SIGINT Summary” stated that February 17 was the most likely date for the Soviets to attempt another circumlunar mission. It also reported on the locations and plans for the Soviet space event support ships Komarov and Bezhitsa, as well as support ships Ristna and Dolinsk, and the missile range instrumentation ship Suchan. The NSA had determined that Komarov, for instance, was advised to return to Havana after stopping at Gibraltar. The summary noted that Havana was the vessel’s “primary support station for circumlunar missions.”

| What the NSA analysts did not realize was that the Soviets were planning two launches in later February, not one. |

A recently declassified cable produced by the National Security Agency’s Defense Special Missile and Astronautics Center (DEF/SMAC) and designated “Top Secret UMBRA,” provided additional, if cryptic, details. DEF/SMAC was created in 1964 to focus on Soviet missile and space launch events, and operated a 24-hour Watch Center that produced cables sent to senior officials within the US military and government. The declassified cables indicate that the NSA had evidence of two pending launches, one early in the month, and a “circumlunar mission which is anticipated around 21/22 February.” But other declassified cables imply that the early February launch was apparently soon dismissed, whereas the NSA had increasing evidence for a later launch.

At the time the Soviets communicated with their tracking ships via shortwave radio and the NSA obviously monitored these communications. Even if the Soviets used code words to conceal the locations where they were sending the ships, the very fact that the ships were being sent to sea or told to return to port was valuable information.

What the NSA analysts did not realize was that the Soviets were planning two launches in later February, not one. Both launches were planned to have simultaneous countdowns, with a Proton rocket carrying a Lunokhod rover to the Moon launching on February 19 followed by an N-1 rocket launching on February 21. If the operation was successful, the Soviets would have demonstrated an important operational capability that could be used for later lunar missions involving cosmonauts.

By February 15, another “SIGINT Summary” indicated that the deployment of Soviet space support ships was such that they probably were not going to support a launch on February 17, but more likely on February 21 or 22. According to the rules of orbital mechanics, those dates were less ideal if the Soviets were sending a spacecraft to the Moon. In fact, rather than a nearly direct path to the Moon, like the Soviets had previously attempted, they would have to place a spacecraft in low Earth orbit first and then later fire its engines to head for the Moon. An NSA cable actually noted that this would be a useful capability for the Soviets to develop.

In fact, it was precisely what the Soviets were seeking to do with the February 19 Proton launch of the Lunokhod rover. The Proton would launch the Lunokhod into low Earth orbit and after multiple orbits, on February 20 the upper stage would boost the Lunokhod out of Earth orbit and toward the Moon. The Soviets never got that opportunity. Soon after launch the Proton suffered a failure and exploded. The Lunokhod had a radioactive power source, and radioactive debris fell on the Soviet Union. The US intelligence community was unaware of the launch or the failure.

The Soviet space tracking ship Komarov. The movements of these tracking ships were closely followed by the National Security Agency because they provided indication of upcoming launches. The NSA had other sources of information on upcoming launches, possibly including communications and telemetry intercepts from the launch site itself. |

By February 21, a classified NSA “SIGINT Summary” declared “Major Soviet Space Event Cancelled.” The event “has apparently been postponed,” the document stated. Support ships Bezhitsa and Keostrov were being redeployed, which “suggests that the event will not take place this month.”

| The declassified documentation, although containing extensive deletions that make interpretation difficult, provide some interesting insights into the NSA’s abilities and limitations at predicting Soviet space launches in early 1969, particularly when the activities, like the Lunokhod and N-1 launches, were entirely new. |

But despite extensive deletions in many of these documents, it is also clear that the NSA had other sources besides the movement of Soviet tracking and recovery ships that indicated a pending launch. These sources undoubtedly included communications intercepts. For example, one DEF/SMAC document refers to “Comments an indication that additional launches in this program are planned in the next few months… [deleted several lines of text.]” Another DEF/SMAC document indicated that on February 21, Soviet civil air facilities announced that entrance into the Tyuratam area was forbidden for a period of time. No reasons were given.

One method the US intelligence community had of detecting pending launches from Tyuratam was observing the travel of Soviet officials to the launch site: if a bunch of them suddenly headed to Tyuratam in Kazakhstan, it meant that something was up. They may have gathered this information via communications intercepts of Soviet VIP aircraft flights.

It is also possible that one or more American signals intelligence satellites in low Earth orbit had detected communications at Tyuratam associated with a launch. Even if the Americans could not decode the signals, an increase in communications traffic would imply preparations for launch.

By late February, NSA analysts had not seen any evidence of a failed launch from the Tyuratam range. DEF/SMAC’s analysts produced another cable. “Although there was extensive evidence of a buildup for major space operation from Tyuratam, probably on 22 February [over one line deleted from text] no attempt to conduct such a launch was detected.” The cable continued: “Available evidence does indicate, however, that key Soviet support entities remain in a posture of readiness: two Soviet space event support ships (SSESS) have taken up stations in the South Atlantic… [over five lines of deleted text]. Evidence as to the intended mission continues to be contradictory; however, it does appear that an unmanned but man-related recoverable spacecraft is to be flown on a parking orbit/ejection profile with ejection occurring over the South Atlantic. Whether or not a lunar flight is involved is not certain, but would be suggested.”

The declassified documentation, although containing extensive deletions that make interpretation difficult, provide some interesting insights into the NSA’s abilities and limitations at predicting Soviet space launches in early 1969, particularly when the activities, like the Lunokhod and N-1 launches, were entirely new. What the NSA analysts did not realize was that the launch preparations they detected in February were not only for another Proton launch carrying a different payload—the Lunokhod—but also preparations for launching an entirely new Soviet rocket, the N-1.

In yet another declassified DEF/SMAC cable, NSA analysts wrote that they considered February 19 to be the most likely date for a launch, but one had probably not occurred. Intelligence evidence “suggests that a valid launch was intended, but that the activity probably terminated in a cancellation [several deleted words] although it is possible that the vehicle could have actually been launched, but failed very early in flight.” This is in fact what happened with the Proton carrying Lunokhod. Two days later, on February 21, the giant N-1 rocket rose into the air and flew downrange before exploding. American photo-reconnaissance satellites that later overflew the area did not spot any debris on the ground because it was too scattered.

Several months later the NSA again detected evidence of an impending rocket launch. That story will be covered in part 2.

Next, in part 2: The July 1969 Explosion of the N-1 Rocket