Has the space launch industry been too focused in the last 70 years?by John Hollaway

|

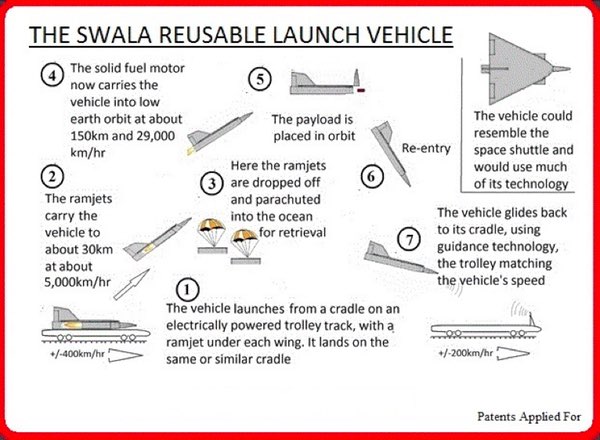

| Swala could be the first true RLV, with a turnaround measured in days or hours, not months or weeks. Nonetheless all its components are well proven—indeed, most of the technology can only be described as elderly. |

However, this diagram has reappeared because of another article about small launch vehicles that recently appeared here (see “Will 2017 finally be the year of the small launcher?”, The Space Review, December 19, 2016). The article concluded that, despite a great deal of hype in this industry, there is only one near-certain small launch vehicle that will lift off in 2017, the non-reusable Pegasus rocket of Orbital ATK, which has already logged more than forty launches. What really is certain is that the big players, like Blue Origin and SpaceX, don’t see putting small satellites into LEO as the principal market for their mega-rockets. The field remains open.

This writer cannot pretend to be a rocket scientist, and his Swala proposal has raised some eyebrows. But the key patent claims—those relating to the use of jettisonable, recyclable ramjets and the vehicle’s landing on a carriage of matching speed—have been accepted (International Patent Application PCT/IB2016/054390). Perhaps more impressively, DARPA, in the form of Jess Sponable, who is overseeing the XS-1 RLV competition there, has written that Swala “is innovative and appears feasible.”

However, there is an aspect of this upstart proposal that is more important than the concept itself. Swala could be the first true RLV, with a turnaround measured in days or hours, not months or weeks. Nonetheless all its components are well proven—indeed, most of the technology can only be described as elderly. Yet it has had to wait until the conventional space industry was 70 years old, and even then it originated from a consultant in the mining industry. Why?

What I think has happened is this. The progenitor of all our launch activity is the German V-2 rocket. Going through the documentation, one cannot but be enormously impressed by the way in which the Nazis overcame all the novel challenges they encountered. The principals of the propulsion, motor, and guidance systems have all come down to us largely unchanged. These, developed at terrible human cost, had worked well and after the war there was nothing else available that could send atomic bombs to a distant enemy. So, directly from the V-2 came the ICBMs and then Sputnik, Yuri Gagarin, the Moon shots, and everything else that has gone into space for the best part of seven decades. A combination of urgency and the availability of state funding kept designers to the straight and narrow.

| However, the new entrants, themselves novices, still encountered only the received wisdom, and the result has been that both the “reusable” space launch rocket designs, despite being technical achievements of the highest order, have conformed to convention. |

A well-worn phrase describes what has happened to allow the upstart Swala concept to prosper: “tunnel vision.” This is an insidious problem that tends to be prevalent in big old organizations, and the state-funded mega-institutions associated with space, including the military, are particularly vulnerable. Consequently, it was not from these but from the private wealth generated by the information revolution that allowed fresh thinking to re-invigorate the industry.

However, the new entrants, themselves novices, still encountered only the received wisdom, and the result has been that both the “reusable” space launch rocket designs, despite being technical achievements of the highest order, have conformed to convention. As a result, they are not fully reusable. It appears that the second stage in these cases will be discarded, while the extra fuel and oxygen needed for the booster to return reduce the payload and hence income by about 30 percent. Indeed, it is tempting, if unfair, to quote Dr. Johnson: “Like a dog walking on its hind legs; it is not done well but you are surprised to find it done at all.”

But what these mighty vehicles can do is to take huamns into deep space, which is something that the Swala RLV, as it is presently envisaged, probably never will. Probably.