CEV: let’s try and clear this up once and for allby Taylor Dinerman

|

| Compared to the vague design references to the CEV in the Explorations Systems Interim Strategy paper published last fall, the original JSF requirements were a model of clarity. |

Since the DoD’s F-35 Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program is somehow supposed to be a model for CEV, it might be instructive to look at why the JSF program was established at all. It came directly out of the failures of the Navy’s aviation establishment and its contactors to design credible replacements for the A-6 Intruder and the F-14 Tomcat. The Advanced Tactical Aircraft (ATA) and the Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) were both, from the Navy’s point of view, miserable failures. After a bit of mucking about with other concepts, the JSF program was begun with the goal of procuring an affordable, multi-purpose combat aircraft that could also be sold to the Air Force and the Marines as well as allied nations.

The JSF has turned into the world’s largest (and some say last) major manned fighter development program. Three to four thousand, or maybe more, aircraft may be built. While many experts have their doubts about the international aspects of the JSF, the program has been slowly moving ahead in spite of the normal delays and weight problems that have plagued military aircraft projects since the Wright Brothers.

For the space community, the fact that Craig Steidle was the JSF head honcho before moving to NASA and taking over the new Exploration Systems Mission Directorate, which is managing the CEV, his presence may mean that the JSF program will somehow be a template for CEV. This may create some confusion.

Compared to the vague design references to the CEV in the Explorations Systems Interim Strategy paper they published last fall, the original JSF requirements were a model of clarity. At the very least, they made it plain that the aircraft was supposed to actually drop bombs and fire weapons. After watching NASA tiptoe around the architecture studies and the spiral development strategies without ever actually making it plain what they wanted the CEV to actually do, one has to wonder what the JSF might have looked like if it had been developed on a similar basis:

“We have a great airplane here, Congressman. True, it can’t actually drop bombs or fire missiles because we didn’t think that was what the Navy wanted. Oh sure, there are bombs and missiles on board but we didn’t build in any bomb bay doors because that would have been too expensive, and we were working to a strict budget.”

At some point soon, the Exploration Systems office is going to have to tell the contractors and the public, in plain and simple English, what it wants the CEV to do, and to present a rough schedule for accomplishing those goals. They cannot hide behind architecture studies for much longer. Maybe they cannot say now whether this system will land directly on the Moon after take off from the Earth, but they should be able to answer some other questions.

| The Exploration Systems office will soon have to tell the contractors and the public, in plain and simple English, what it wants the CEV to do, and to present a rough schedule for accomplishing those goals. |

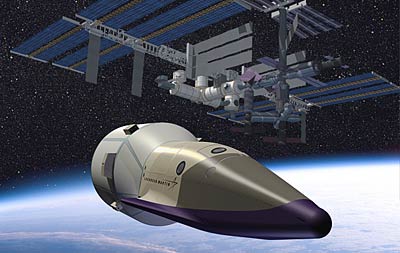

If the CEV is going to the ISS, will it fulfill a lifeboat and taxi function or will it just fly a few missions up there, after which it will no longer visit the station? Will the CEV have the capacity to visit other places in cislunar space, for example, the Lagrange points, or geosynchronous Earth orbit? Will the CEV have the capability to remain in space for longer periods than the shuttle, which was limited to about two weeks?

Since they hope to make the CEV a modular system, will it have the capability to be reconfigured in space, or will the modularity aspect be fixed before every launch, which brings up the question of refueling in orbit? A CEV that cannot be refueled is going to be seriously limited in its exploration capacity. Which, in turn, will bring up the whole question of what kind of in space propulsion they want to use.

Unless NASA can make it clear what exactly it plans to do with the CEV, and unless the agency can clearly show that the CEV system is going to be truly multipurpose, Congress, and perhaps future Presidents, are going to have a hard time supporting the Vision for Space Exploration.