Shadow dancing: the Satellite Data Systemby Dwayne A. Day

|

| Although it carried a highly classified mission payload—“black” in the jargon of the intelligence community—the satellite itself was developed and procured by the unclassified—“white”—Air Force Space and Missile Systems Office, thus straddling the edge of the shadowy world of satellite reconnaissance. |

The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) was the organization that was responsible for overseeing the development of intelligence satellites. The NRO included an Air Force component known as Program A and publicly acknowledged as the Secretary of the Air Force Office of Special Projects, or SAFSP. The NRO also included a CIA component housed in the CIA Deputy Directorate of Science and Technology's Office of Development and Engineering and known as Program B, which was then leading the ZAMAN effort. Program A and Program B had often battled each other for primacy within the NRO. In 1969, NRO officials began planning for relay satellites, and by June they became a separate line item in the NRO’s budget. The relay satellite program formally began in spring 1970 when a preliminary evaluation selected a small number of civilian firms for a year-long system definition phase to begin in July of that year. The plan was to down-select to a single company in October 1971.

Using an additional satellite system in high orbit to relay images from ZAMAN satellites in low Earth orbit would be both expensive and complicated. But it also offered advantages over the direct transmission to ground approach, including longer transmission times. An added advantage of the relay system was that it enabled multiple satellite constellations, not just a single satellite at a time. Another advantage was that the imaging and relay satellites would be very far from each other and the ground station and it would be difficult for the Soviets to determine that the satellites were working together, thus increasing operational security.

Some of the details of both programs remain classified, but while these early decisions about the data relay satellite were being made, ZAMAN was still primarily a technology development program, not an approved satellite development program. Nevertheless, it was clear to those running the National Reconnaissance Program—the formal term for the collection of top secret intelligence satellites managed by the NRO along with their budgets—that these new systems were going to be very expensive. That created a dilemma for the National Reconnaissance Office leadership, who sought to be low-key even among those who had security clearance to know about the NRO.

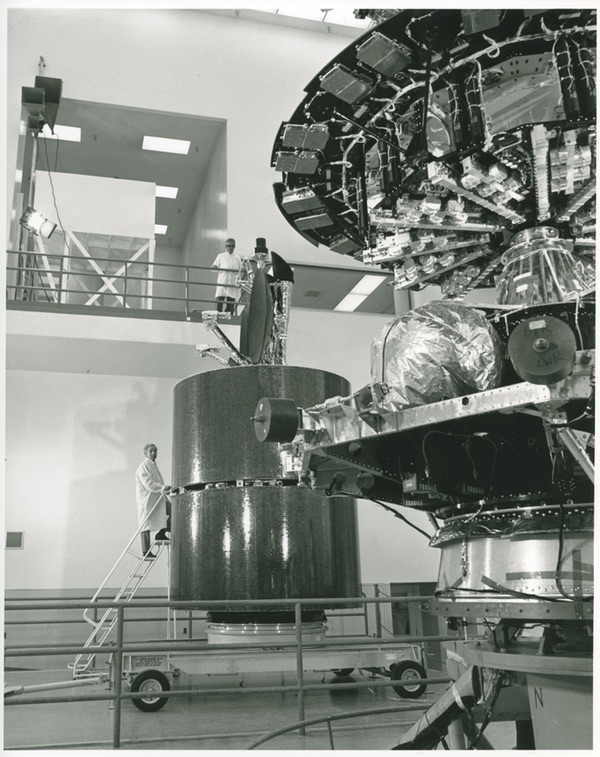

Two Intelsat IV satellites under construction at Hughes in California. Hughes developed numerous spin-stabilized communications satellites during the late 1960s and into the early 1990s, including the Satellite Data System satellites, and the JUMPSEAT signals intelligence satellites. (credit: Hughes) |

Spreading the responsibility and the costs

On August 15, 1969, the NRO’s Executive Committee decided to give relay satellite development to the Space and Missile Systems Office (SAMSO). SAMSO was part of the Air Force Systems Command and not affiliated with the Secretary of the Air Force Special Projects office—the classified NRO Program A office—in Los Angeles. Unlike Program A, SAMSO was both overt and completely outside of the NRO, and giving a non-intelligence organization responsibility for a new satellite vital to national reconnaissance was extremely unusual. The NRO’s ExCom also gave the program an overt designation: the “Satellite Data System,” or SDS.

According to Vance Mitchell’s history of the relay satellite program, there were three reasons to give development responsibility for the Satellite Data System to SAMSO:

- Funding it through Air Force channels would hold down the National Reconnaissance Program budget. The ExCom members were concerned about the NRO budget exceeding a billion dollars, believing that this was a threshold above which their program would receive added political scrutiny from the few elected officials who were cleared to know about the NRO. Other NRO programs had already shifted money into the Air Force side to keep the total NRO budget down. It was not until the early 1970s that the National Reconnaissance Program budget finally crossed the billion-dollar mark.

- Having SDS as an Air Force program would imply to the Soviets that it was not connected to reconnaissance and therefore enhance mission security.

- The Air Force Satellite Control Facility was responsible for communicating with satellites and had acquired considerable experience. In addition, the Aerospace Corporation had been evaluating data relay satellites in 1968 into 1969 and had become knowledgeable about the subject. Aerospace worked closely with the Space and Missile Systems Office.

SAMSO designated the SDS program as secret with a “special access required” (SAR) annex. There were only two other such programs at the time. One was the Defense Support Program (DSP) missile warning satellite, and the other may have been what became the Global Positioning System. SAR allowed the release of selected information about the NRO’s communications relay payload without divulging critical items that might compromise its mission. The CIA’s connection to SDS and details of the NRO communications payload were confined to a special compartment within the NRO’s own BYEMAN security system. Anybody requiring access to this information had to be cleared by the NRO.

| Hansen had justified SDS in front of Congress on the basis of it having more than one payload and did not want to go back to members of Congress and explain why that was no longer the case. In an effort to force both SAMSO and the NRO to develop other payloads for SDS, Hansen suspended funding to SDS and placed the program on temporary hold. |

Once SAMSO was designated in charge of SDS, it immediately led to questions within SAMSO and the Air Force. Air Force personnel involved in SDS development believed that since the Air Force was providing the personnel, expertise, and offices to run the SDS development, SAMSO was now more than a junior partner in somebody else’s program and should be treated as a full partner. Brigadier General Walter R. Hedrick Jr., Director of Space and Deputy Chief of Research and Development, wanted changes in SDS to make it more responsive to Air Force missions. Hedrick wanted the satellites to serve both Air Force and NRO requirements. He wanted to add secondary payloads to the spacecraft in addition to the communications relay payload.

CIA officials connected to the SDS development believed that the SDS satellites were supposed to have a single NRO communications relay payload and no other missions. They were concerned that the NRO might become a “customer” on its own relay satellite and have the satellite’s covert intelligence mission compromised in the process.

By November 1969 there was pressure to create a management agreement that both sides would accept. CIA officials agreed to allow Air Force secondary payloads on SDS, but also demanded a guarantee that the intelligence relay mission still had priority. In March 1970, the NRO accepted the management changes demanded by the Air Force while the Air Force guaranteed the NRO communications mission top priority.

Selecting satellites and payloads for SDS

The contract definition phase for SDS began in August 1970, a few months later than planned. Two contractors were involved: Hughes, and one other aerospace firm whose identity was deleted from the official history but was either TRW or Ford Aerospace. Both companies, like Hughes, were involved in developing communications satellites.

One of the secondary missions initially proposed for SDS was relaying data collected by Air Force DSP missile warning satellites then in development. But in summer 1970 members of the DSP program office—then operating under the deliberately obscure designation of Project 647—began to have reservations about using SDS relays for DSP satellites. Later in the year the Project 647 office withdrew from participation in the SDS in favor of relaying DSP data directly to the ground. That decision required DSP to develop its own ground stations, including a politically sensitive ground station in Australia. It also meant that SDS again became a single payload satellite.

This change annoyed Grant Hansen, the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Research and Development. Hansen wanted dual or multiple users on SDS. In a January 1971 meeting with several reconnaissance officials he discussed the options. Hansen had justified SDS in front of Congress on the basis of it having more than one payload and did not want to go back to members of Congress and explain why that was no longer the case. In an effort to force both SAMSO and the NRO to develop other payloads for SDS, Hansen suspended funding to SDS and placed the program on temporary hold.

In August 1970 three orbital configurations for SDS were being evaluated. The favorite option for several intelligence officials involved putting the relay satellites in geosynchronous orbit. But this was soon rejected. Although it provided good global coverage, it had a high price tag and an unacceptable level of technical risk. The other two options offered less coverage. One of these involved placing satellites in highly-inclined, highly-elliptical orbits so that they would swing low and fast over the South Pole and then head high up over the northern hemisphere, putting them in line of sight with both a low-orbiting reconnaissance satellite over the Soviet Union and a ground station in the United States.

Hansen’s ploy to force SAMSO and NRO to develop other options for the SDS satellites finally started to bear fruit. By early March 1971 Air Force and intelligence officials had identified at least six possible secondary payloads and two were considered most feasible. One of these was relatively minor: a small S-band transponder on each satellite could relay communications between the headquarters of the Air Force Satellite Control and a remote tracking station at Thule, Greenland, ending reliance upon balky land lines.

Another communications payload would support the Single Integrated Operational Plan, the Air Force’s nuclear war-fighting strategy. SIOP required communications with Strategic Air Command B-52 Stratofortress bombers and KC-135 Stratotankers. The SIOP at the time depended on ground-based high frequency broadcasts, which were vulnerable to jamming and nuclear disruption. An SDS payload in Earth orbit would be less vulnerable and could provide coverage in northern regions that were hard to cover. But according to Mitchell’s SDS history, the SIOP payload was regarded as a “heavy mother” requiring a helix antenna, transmitters, receivers, additional solar cells, and cabling and structures weighing over 136 kilograms (300 pounds). In late May 1971, the two contractor teams determined that the SIOP payload was not a good candidate and the Air Force ruled it out for SDS.

Grant Hansen was apparently displeased that once again SDS was being reduced to a satellite system with a very limited mission. A review board including representatives from Hansen’s office slashed SDS funding for fiscal year 1972 in an effort to force program managers to go back and find another payload for the satellites.

General Sam Phillips, who was then in charge of SAMSO but had previously played a major role in running NASA’s Apollo program, protested the funding cut. The relay program was reduced to minimum effort until they could reach an acceptable agreement, or the relay program was taken away from SAMSO and transferred back to the NRO.

Although the specific details are deleted from Mitchell’s history, Mitchell indicates that the SIOP communications payload was eventually incorporated into the SDS satellite design despite its substantial mass and power requirements.

B-52 Stratofortress during refueling operation. The SDS satellites included a secondary payload for communicating with strategic nuclear forces like the B-52s in northern latitudes during the Cold War. (credit: US Air Force) |

Secrecy and its paperwork

According to Mitchell, by spring 1971 there was increasing US Air Force opposition to the special access requirements in place for SDS and the two other space programs because of the difficulties they created for management and operations. Although at least one of the SARs was eliminated around this time, Deputy Director of the NRO Robert Naka wanted to keep the Satellite Data System’s SAR in place. Finally, in January 1972, Director of the NRO John McLucas removed the SAR from the SDS program and withdrew all relevant material into the NRO’s own BYEMAN security compartment.

| The communications relay payload that was developed for the KENNEN used a frequency, 60 gigahertz, that did not penetrate the Earth’s atmosphere. This meant that if the Soviets listened in on the KENNEN they would detect no emissions coming from it. |

General Phillips and one other officer did not think that an entirely covert SDS program was necessary, but they believed that SDS security should be tightened. They and NRO officials agreed that the NRO’s BYEMAN security compartment would be used to protect details on the satellite’s bandwidth, near-real-time operations, transmission, specific frequencies, and the NRO relationship. Documents about the program would be classified at the secret level and would only refer to the secondary payloads. They would also state that SDS satellites were deliberately “over-engineered” in case the Air Force wanted to add more payloads, thus explaining why such a large satellite had a relatively limited communications payload. Previously the NRO payload had been referred to as “User A” but documents would now indicate that User A had been deleted.

The birth of KENNEN

In September 1971, President Richard Nixon formally approved development of the ZAMAN electro-optical imaging system. By November its name was changed to KENNEN, although it would become better known to the public by the designation of its camera system, KH-11. With the imaging satellite development now underway, the Satellite Data System finally had a confirmed primary mission and a deadline requiring that it become operational before the first KENNEN satellite was launched. KENNEN was initially scheduled for an early 1976 launch, although this eventually slipped to late in the year.

The communications relay payload that was developed for the KENNEN used a frequency, 60 gigahertz, that did not penetrate the Earth’s atmosphere. This meant that if the Soviets listened in on the KENNEN they would detect no emissions coming from it, creating the impression that it was passive even while it was sending signals up to the SDS.

At an April 20, 1972, meeting of the NRO’s Executive Committee (ExCom), NRO Director John McLucas was satisfied with existing management arrangements for SDS. SAMSO would continue management, the NRO’s Program B—led by the CIA—would exercise technical oversight, and the Air Force would fund and publicly defend the program to Congress. The NRO officials also established a more streamlined chain of command from SAMSO to the Secretary of Defense level.

The NRO director also moved SDS’s BYEMAN security responsibilities from the CIA-led Program B to the Air Force-led Program A (SAFSP), which strengthened the appearance of a strictly Air Force project and enhanced Air Force authority over the program. He also ordered that there be no further mention at all of a third payload outside the classified BYEMAN security channel, which meant that only people with BYEMAN clearances could speak or know about SDS’s communications relay payload. Information prohibited from public release included the number of satellites, orbits, technical descriptions, launch dates, finances, and mention of ground facilities.

On June 5, 1972, SAMSO selected Hughes to build the satellites. According to a 2011 interview with former CIA and Hughes official Albert “Bud” Wheelon, the winning Hughes design was based upon the company’s proven Intelsat IV spin-stabilized satellite, which weighed over 700 kilograms. The first Intelsat IV had been successfully launched into geosynchronous orbit in January 1971. Although both Intelsat IV and SDS were spinning drums covered with solar cells, SDS had a different set of antennas mounted to a de-spun platform at its top.

Anthony Iorillo, a Hughes engineer, was assigned to the SDS program. Hughes had a problem getting sufficient numbers of its own personnel security clearances, so a number of Air Force officers at the captain and major level with the required security clearances were detailed to work at Hughes.

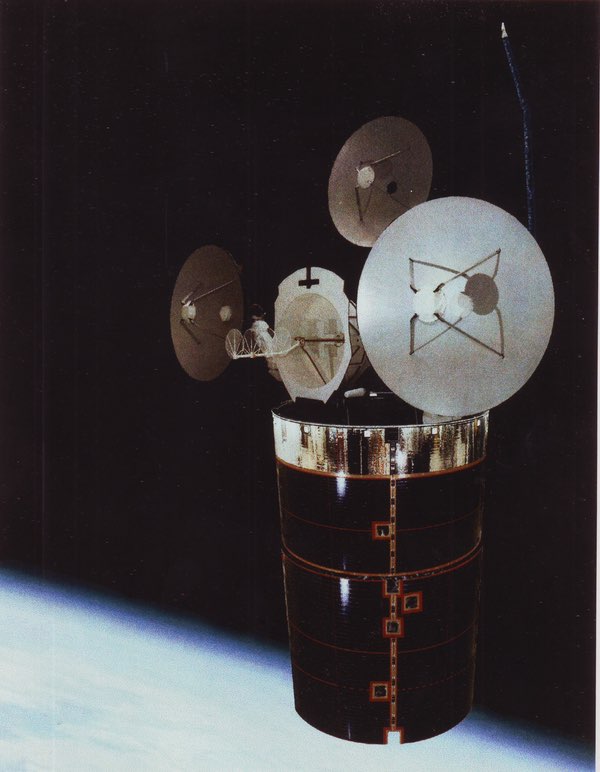

A block 2 Satellite Data System satellite with its antennas deployed. These satellites began replacing the first SDS satellites starting in the late 1980s. (credit: NRO) |

Changes in payloads and operations

The SDS’s primary payload was always the communications relay for the KENNEN reconnaissance satellites. The two secondary payloads were just that—secondary. In August 1974 the Secretary of the Air Force approved adding a third secondary payload to the satellites, the Atomic Energy Detection System. This was introduced starting with the third satellite. Similar nuclear detection payloads—also known as “bhangmeters”—were already carried on Defense Support Program satellites. They could detect nuclear detonations in the atmosphere and space.

| Although the satellites all worked, according to several sources there were early operational problems with getting them to smoothly work together. |

According to declassified Air Force documents, the Air Force started procurement with a structural test model designated X-1, followed by a qualification model designated Y-1 and equipped with most of the electronic systems to demonstrate that the satellite could perform the functions it was designed for. The initial plan was to procure four flight spacecraft (designated F-1 to F-4) and refurbish Y-1 to be a flight spare.

By the first half of 1975, testing of X-1 was completed, assembly of Y-1 was completed and it was undergoing initial testing, and fabrication of F-1 was well underway. By November 1975, the Air Force approved procurement of two additional satellites, F-5 and F-6, which were supposed to be compatible with the space shuttle.

The first two SDS satellites were launched into orbit atop Titan III-34B rockets in June and August 1976. The first KENNEN was launched in December that same year. Although the satellites all worked, according to several sources there were early operational problems with getting them to smoothly work together.

In 1977, a CIA employee sold a copy of the KH-11 user’s manual to the Soviet Union, giving away many of the secrets of the KENNEN satellite. However, Mitchell’s history hints that the Soviet Union did not understand the connection between the KENNEN and SDS satellites until the summer of 1978, confirming a claim that program planners had made about SDS early on, that it would be difficult for the Soviets to figure out that the satellites in highly different orbits were part of the same mission, especially since the KENNEN did not appear to be transmitting while over Soviet territory.

The fourth and fifth SDS satellites were delivered in May and October 1980, and Y-1 was refurbished, redesignated F-5A, and delivered in May 1980. In 1981 the Air Force proposed purchasing satellite F-7. It is unclear how many of these satellites were eventually launched, and one or more may have been retired to a classified storage facility at the end of the program.

Eventually, the first series of satellites were replaced by an updated version designed to be compatible with the shuttle from the start and apparently based upon the large Hughes Intelsat VI communications satellite. The NRO surprisingly released photos and video of these later block 2 satellites in the late 1990s. Equally surprisingly, in early 2017, NASA revealed that it had been offered a spare satellite from an unnamed government agency. That satellite was clearly one of these block 2 vehicles. (See “Spinning out of the shadows,” The Space Review, March 13, 2017.) At some point, possibly even early during the 1970s, the SDS program received the classified code name QUASAR. That name was reportedly still being used into the 21st century.

The more things change…

In October 1976, the Air Force announced long-range plans that did not include SIOP payloads on future SDS satellites. Instead, the SIOP payloads would be mounted on the planned Air Force Milstar communications satellites. Milstar was a highly ambitious and complex communications satellite system that would support multiple Air Force requirements. When first conceived, the Air Force planned to have Milstar satellites in geosynchronous orbit as well as a constellation of satellites in medium-altitude polar orbits. The satellites in their different orbits would be able to communicate with each other, creating a complex interlocking communications network around the Earth. They were also supposed to be protected against enemy jamming and hardened to survive the effects of nuclear weapons. If it worked as planned, Milstar would provide a tremendous leap in communications capability for multiple Air Force and other users.

| The early Air Force plan was for Milstar to begin operations in 1982, but Milstar soon ran into major development problems. Ultimately, the first Milstar did not launch into space until 1994. |

The CIA’s Leslie Dirks asked members of his staff to evaluate including the SDS relay capability on the Air Force’s Milstar. The initial concept was for three Milstar satellites in polar orbits to perform the relay capability for future KENNEN satellites. But CIA officials quickly grew skeptical about this proposal. Milstar was going to be very complex and face technical risks and problems in development resulting in delays which could affect the KENNEN relay mission. In addition, the NRO’s communications relay payloads would then become secondary payloads for satellites that had many other Air Force missions. CIA officials questioned what would happen if one of the NRO’s payloads failed on a Milstar satellite—would the Air Force launch an expensive replacement satellite simply to fulfill the NRO’s requirement? Two of Dirks’ aides recommended against putting the KENNEN communications relay payload on Milstar and Dirks agreed.

Dirks’ decision proved to be a good one. The early Air Force plan was for Milstar to begin operations in 1982, but Milstar soon ran into major development problems. Ultimately, the first Milstar did not launch into space until 1994. The Air Force had to postpone plans to transfer the SIOP communications payload from SDS to Milstar, and SDS continued carrying SIOP payloads into the 1990s.

Artist concept of an early Milstar satellite. In the late 1970s there was a proposal to put the data relay payload on the Milstar satellites. NRO officials eventually rejected this proposal, preferring to keep the dedicated SDS satellites. This proved fortuitous, because Milstar was greatly delayed entering service. (credit: US Air Force) |

Shuffling responsibilities

Dirks’ decision to not transfer the KENNEN communications relay payload to Milstar meant that the SDS program would have to continue, and since the Air Force no longer had a requirement for SDS, the program would have to be transferred to the NRO, with NRO funding and BYEMAN security measures. In November 1981, NRO Director Pete Aldridge approved the transfer of responsibility for SDS.

Aldridge’s decision created controversy. Brigadier General Jack Kulpa, who headed SAFSP and was therefore the NRO’s Program A director, lobbied to transfer the SDS from SAMSO into Program A, arguing that this would provide continuity and Program A had sufficient experience to run the program, although KENNEN was run by the CIA’s Program B and there was still an ongoing rivalry between personnel in Programs A and B. Yet another suggestion was to create an NRO Program D office solely to manage the relay satellite program.

SDS Director Colonel Clyde McGill and his supervisor, SAMSO commander Lieutenant General Richard Henry, lobbied to leave SAMSO responsible for SDS. They argued that withdrawing SDS into the National Reconnaissance Program benefitted nobody. Both the NRO and the Air Force needed SDS to serve as a “bridge organization” that could work in both the white and black worlds and provide access to evolving technologies for both sides. Although Mitchell’s history of SDS is unclear on this point, apparently Henry and McGill were successful at convincing Aldridge to maintain SDS as a SAMSO-led program, at least for a few more years.

The NRO will apparently declassify information about the early years of the KENNEN program sometime in 2018. If it does, we may learn more about SDS and its mysterious dance between the black and the white space communities.