The asteroid mining bubble has burstby Jeff Foust

|

| “The DSI team provided very innovative solutions to the problem of exploring the solar system at a reasonable cost, and we are eager to see if that can be developed with the help of Bradford technologies,” Fichtenbaum said. |

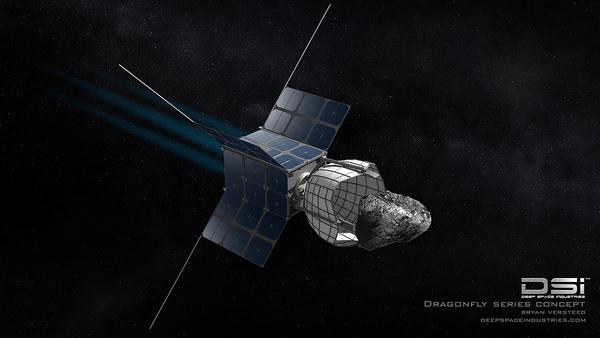

Yet those obstacles didn’t stop two companies several years ago from starting up with goals of harvesting resources from asteroids. First came Planetary Resources, which announced plans in 2012 to develop asteroid mining systems , with the backing of prominent business people (see “Planetary Resources believes asteroid mining has come of age”, The Space Review, April 30, 2012.) Nine months later, Deep Space Industries (DSI) announces its own, similar asteroid mining plans (see “Asteroid mining boom or bubble?”, The Space Review, January 28, 2013.)

Six years later, the answer to the question posed in that headline is clearly “bubble.” In just two months, both DSI and Planetary Resources, which struggled to raise money and even shifted focus away from asteroid mining, have been acquired by other companies. Their plans to harvest the riches of the solar system are on hold, perhaps indefinitely.

On New Year’s Day, Bradford Space announced its acquisition of DSI. Bradford, owned by a US investment group, the American Industrial Acquisition Corporation, but with facilities in Europe, manufactures spacecraft components, including a non-toxic propulsion system called ECAPS.

DSI had been working on its own non-toxic satellite thruster, called Comet, that uses water as propellant. That was billed by the company as a way to stimulate demand for space resources (most existing spacecraft use propellants, like hydrazine, not readily available from asteroids) but also as a shift in focus in the company, at least in the near-term, from asteroid mining to smallsats, a field with clear and growing demand.

Bradford saw Comet as complementary to its own ECAPS system. On last month’s SpaceX Falcon 9 launch of 64 smallsats, four of the spacecraft were equipped with Comet thrusters while three had ECAPS thrusters.

“Bradford gets a lot of interesting things from the addition of DSI, namely a very complimentary propulsion product (Comet), good customers and order book, a great engineering and production team, a position in Silicon Valley and in the US (which is important for Bradford, which until now was almost entirely Europe),” said Ian Fichtenbaum, a director of Bradford Space. He added that, besides helping Bradford sell its technologies to US customers, the deal will make it easier to sell Comet thrusters to European customers.

DSI was also working on a satellite bus, called Xplorer, intended for use on deep space missions, including the asteroid prospecting and mining missions that the company eventually planned to pursue.

Bradford, Fichtenbaum said, plans to continue that development of Xplorer. “The DSI team provided very innovative solutions to the problem of exploring the solar system at a reasonable cost, and we are eager to see if that can be developed with the help of Bradford technologies,” he said in the announcement.

In many respects, Bradford’s acquisition of DSI is a relatively conventional industry development: one component provider acquires another, looking for the expanded markets and economies of scale that a larger company can provide. But what happened to Planetary Resources is, well, less conventional.

Two months before the DSI announcement, Planetary Resources announced that it, too, had been acquired by another company. ConsenSys, which describes itself as a “blockchain venture production studio,” said it purchased Planetary Resources in a transaction terms of which were not disclosed.

| “Bringing deep space capabilities into the ConsenSys ecosystem reflects our belief in the potential for Ethereum to help humanity craft new societal rule systems through automated trust and guaranteed execution,” said Lubin. |

ConsenSys uses blockchain technologies, in particular a decentralized computing platform called Etherium, for “building and scaling tools, disruptive startups, and enterprise software products,” according to its website. ConsenSys has more than three dozen “spokes,” or companies working on various projects that make use of Ethereum, in areas ranging from financial management to gambling.

Even with that eclectic mix of companies, it’s not clear how an asteroid mining company fits in, and the announcement of the acquisition didn’t provide many hints. “Bringing deep space capabilities into the ConsenSys ecosystem reflects our belief in the potential for Ethereum to help humanity craft new societal rule systems through automated trust and guaranteed execution,” said Joe Lubin, founder of ConsensSys. Okay.

“And it reflects our belief in democratizing and decentralizing space endeavors to unite our species and unlock untapped human potential,” he added. “We look forward to sharing our plans and how to join us on this journey in the months ahead.”

ConsenSys and Planetary Resources have not shared additional details since that announcement at the end of October. It was clear long before then, though, that Planetary Resources needed more financial resources: a funding round in 2017 involving a “major global mining company” fell through. That lead to significant layoffs earlier last year. In its announcement of the acquisition, ConsenSys identified only two people from Planetary Resources who would be staying on: president and CEO Chris Lewicki and general counsel Brian Israel.

It’s not clear that ConsenSys will be able to provide significant resources. The company said last month it was laying off 13 percent of its own staff while planning to spin off many of those spokes, which may not be equipped to operate on their own. The company has cut back on spending in other areas, a dramatic change from its earlier, freewheeling days.

Evan as Planetary Resources’ future remains uncertain, DSI, under new ownership, hasn’t completely ruled out asteroid mining. “We believe in developing and exploring the riches of the solar system and we want to be among the ones to make it happen,” said Fichtenbaum in the statement announcing the acquisition.

But doing so, he said later, would be done under a more methodical approach. “There is a lot that needs to be developed before people are mining asteroids,” he said. “But that doesn’t mean that there aren't markets for solutions that solve key problems, like for high performance propulsion systems, deep space buses and precision control systems.”

“For commercial asteroid mining, we are not people who sneer at its prospects,” he added. “We believe it has a real future and want to see if DSI's Comet and Xplorer as well as Bradford’s existing activities can play a part of that future. In terms of doing the mining activities ourselves, you never know—we will see! But for now, we are taking things step by step.”

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.