Why the Chang’e-4 Moon landing is uniqueby Namrata Goswami

|

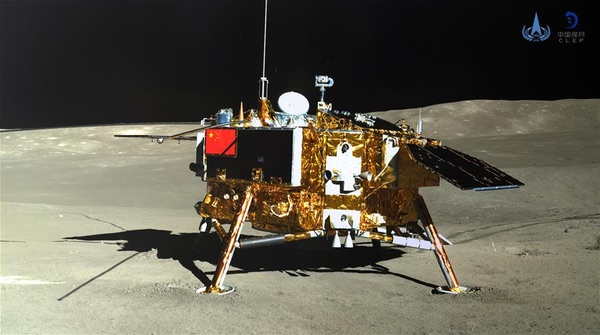

| What is critical to realize is that the Chang’e-4 is a unique demonstration of Chinese capabilities in spaceflight, including establishing access to and surveying the lunar farside, as well as searching for lunar resources. |

In order to analyze whether its long-term goal of establishing human presence on the Moon will be accomplished, Chang’e-4 is carrying a three-kilogram aluminum alloy cylinder that contains seeds of potatoes and Arabidopsis, a plant related to cabbage, as well as eggs of silk worms. The idea is to experiment if potatoes and silk worms can flourish on the Moon in simulated mini-biosphere. This is exciting by itself, as it is the first time that such an experiment is being carried out on the Moon, nearly 400,000 kilometers from Earth, unlike similar experiments carried out on the International Space Station (ISS) and Tiangong 2, in low Earth orbit (LEO), just 400 kilometers above the Earth. What makes this experiment unique is that it is the first step in analyzing whether humans can create suitable conditions on the Moon to survive for the long term and is directly connected to China’s stated ambition of establishing a permanent human presence on the Moon.

The mini-biosphere experiment on Chang’e-4 is a collaborative effort of 28 Chinese universities led by Chongqing University. Its chief designer, Xie Gengxin, said:

We have to keep the temperature in the “mini biosphere” within a range from 1 degree to 30 degrees [Celsius], and properly control the humidity and nutrition. We will use a tube to direct the natural light on the surface of Moon into the tin to make the plants grow…We want to study the respiration of the seeds and the photosynthesis on the Moon.

So why potatoes and Arabidopsis? According to Liu Hanlong, Chief Director of the experiment and Vice President of Chongqing University, “The growth period of arabidopsis is short and convenient to observe. And potatoes could become a major source of food for future space travelers…Our experiment might help accumulate knowledge for building a lunar base and long-term residence on the Moon.”

China’s long-term goals of space presence, access, and dominance by 2045 is emboldened by the successful landing of Chang’e-4, not an easy feat to carry out on a side that faces away from Earth. The landing site of the spacecraft, Von Kármán crater, is part of the South Pole Aitken Basin, whose expanse may contain volatile and mineral resources essential to human settlements.

In his book The Value of the Moon, the late Paul Spudis said the Moon’s “greatest value is its capacity to create new spacefaring capabilities through the exploitation of its material and resources.” He believed once we develop the skill to master the lunar surface and exploit its resources, humanity can become a true spacefaring specie. Spudis recommended the use of small robotic rovers to traverse the lunar poles to search for water ice and other resources.

In September 2018, Li Guoping, Director of the Department of System Engineering at the China National Space Administration (CNSA), stated that China will be sending robotic probes to the lunar poles by 2030. The aim of the probes, according to Li, will be to explore the lunar south pole region to analyze the composition of the isotopes of hydrogen, carbon, helium, and oxygen deposited there by the solar wind. The rover that will explore the north pole of the Moon will examine whether ice exists in permanently shadowed areas there. Those probes may be the final step before establishing China’s scientific research base by 2035.

The Queqiao, or Magpie Bridge, relay satellite launched in May 2018 and placed in the L2 halo orbit to serve as a communication relay satellite from the Chang’e-4 can see into lunar polar craters, enabling future landing zones for China’s probes in the shadowed regions. Significantly, for purposes of space resources, the Chang’e-4 rover, Yutu-2, has a radar that can penetrate the lunar surface to look for resources. A study of the Moon’s surface also offers us an insight into how our solar system evolved.

| While the West tends to underplay China’s space capabilities with a tendency to call it largely propaganda by the Communist Party of China, is it really the case? |

The next 10 to 15 years promises to be exciting times for China’s space program. Chinese ambitions include a reusable rocket by 2035, nuclear-powered “space shuttles” by 2040, and a space-based solar power satellite by 2050. Wang Changhui, who is Associate Professor of Aerospace Propulsion at the School of Astronautics at Beihang University in Beijing, stated that “The nuclear vessels are built to colonize the solar system and beyond”.

While the West tends to underplay China’s space capabilities with a tendency to call it largely propaganda by the Communist Party of China, is it really the case? When China started the Tianzhou spacecraft resupply program in 2010 and gave the contract to CAST to develop it in 2011, declaring it will launch the cargo spacecraft by 2016–2017, it was written off in the West as mere propaganda and building prestige for the Party. Yet Tianzhou-1 was successfully launched and docked with the Taingong-2 in 2017.

In July 2016, CNSA announced that by the end of 2018, it will send a probe to the far side of the Moon, another achievement it accomplished nearly on schedule. The world is now waking up to the future potential of China’s space dream: of establishing a long-term presence, and dominance, of outer space.

Note: we are temporarily moderating all comments subcommitted to deal with a surge in spam.