Excessive pessimism: a side effect of Potomac Fever?by Taylor Dinerman

|

| By 1987 Reagan and his supporters had convinced a large part of the GOP electorate, and even a few Democrats, that America had to move away from MAD and towards strategic defense. |

McFarlane was, and is, an intensely intelligent, idealistic, and patriotic American. I vividly remember him giving a comprehensive and heartfelt justification of US Central American policy to a gaggle of sneering European journalists at the 1985 Reagan-Gorbachev summit in Geneva, a policy that was thoroughly vindicated by the 1990 electoral victory of Violetta Chamorro over the Sandinistas. Yet, at the same time he was explaining why the US was resisting Communism in Central America, he was, according to this book, ready to trade away the whole core of the missile defense research program for a few concessions in the long-range strategic weapons talks.

He was convinced that whatever advantage the US had gained by beginning the “Star Wars” program was a wasting asset. The Soviet propaganda campaign, political hostility at home and overseas, and ever-present budgetary pressure would combine to kill off the whole project. Therefore, he thought it would be wise to trade it for whatever concessions the Soviets would offer rather than continue the research and face the possibility that SDI would be shut down. One opponent of “Star Wars” even called it “a technological Vietnam”. McFarlane and others feared that it would end the same way; Congress would cut off the funds and everything would end in ignominious defeat.

When the Democrats won back control of the US Senate in 1987 they were able to make serious cuts in the SDI budget, but by then it was too late. Reagan and his supporters had convinced a large part of the GOP electorate, and even a few Democrats, that America had to move away from MAD and towards strategic defense. In spite of all the confusion, ignorance and obstacles, America was moving decisively away from a strict reliance on nuclear deterrence. The momentum was such that not even the election of Bill Clinton and of Democratic majorities in both the House and Senate in 1992 could fully stop it.

After the GOP took control of Congress in 1994, national missile defense became a Congressional priority and the Clinton Administration more or less decided that it was not worth the fight. Conceptually at least, Reagan had won. The pre-1980 philosophy of MAD plus arms control is slowly being replaced by a new paradigm of defense plus unilateral restraint.

| What the VSE is accomplishing is to break down the shuttle/station iron triangle and replace it with a new one centered on the CEV and its ancillary systems. |

This has been done on a budget of that has varied from about seven to about eight billion a year. This is roughly the same amount that NASA has been planning to spend on the human side of the Moon-Mars program known as Vision for Space Exploration. It seems that Congress is able to sustain long-range programs as long as they cost less than ten billion a year. That seems to be the price that America is willing to pay for what are sometimes denigrated as futuristic dreams.

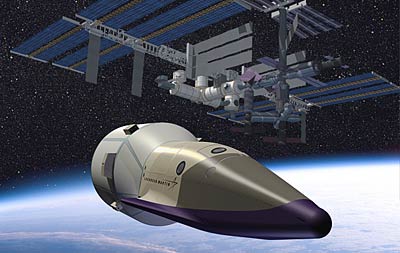

The lesson for NASA and the supporters of the VSE is that once an idea has been funded and fought over through two or three budget cycles it becomes embedded in the political culture and is difficult if not impossible to replace. This is sometimes called the “Iron Triangle” of the President, Congress, and the Contractors. What the VSE is accomplishing is to break down the shuttle/station iron triangle and replace it with a new one centered on the CEV and its ancillary systems. This will eventually get NASA out of low Earth orbit and will do so without a massive budget increase.

Pessimism is a comfortable and easy position to maintain. Washington abounds with a sort of enforced cynicism that makes it easy to imagine that nothing will ever change and that everything is falling apart. As the VSE moves forward optimism makes a lot of sense. George W. Bush’s January 14, 2004 speech may yet stand with Ronald Reagan’s Star Wars speech as examples of long-term, visionary, Presidential leadership.