Space weapons: the new debateby Taylor Dinerman

|

| Our potential foes have come to see these space systems not just as vulnerable but, essentially, defenseless. |

Together, these systems constitute America’s military spacepower. They provide the leverage that allows pilots in Nevada to control armed Predator drones in the skies of Afghanistan and Iraq. They allow a battalion commander in Baghdad to keep track of every vehicle in his unit at a glance from a screen inside his command tank. The Secretary of Defense and the President use it to keep track of any major military operations, worldwide. Comprehensive military spacepower defines what it means to be a superpower in the 21st century.

For the moment, the US has extremely limited options when it comes to defending its satellites. If a space object is detected and confirmed as hostile, the US operators could order the US spacecraft to move out of the way. Even if successful, this is a limited and ineffective way to defend a satellite, since it uses up precious onboard maneuvering fuel. Even a primitive enemy antisatellite (ASAT) weapon could cut years off the lifespan of a multi-billion dollar asset.

The US has a few near-term antisatellite options. There is an existing satellite jamming weapon called the Counter Communications System. This Earth-based device stops a satellite’s operation but does no permanent damage. Very little information has been released on its effectiveness. Since it operates from the ground and its effects are supposedly reversible, it has not generated the controversy associated with “space weapons.”

There has been talk that the Airborne Laser (ABL) could be used as an ASAT weapon. The ABL is a 747 equipped with a chemically-powered laser, designed to shoot down Scud-type missiles as they are taking off. This is called the “boost phase,” and it is the time when ballistic missiles are most vulnerable. It has been suggested that the ABL may be able to blind or seriously damage a satellite in low orbit. This weapon could also conceivably be used to help deorbit pieces of space debris.

Other possible antisatellite weapons are the Ground-based Missile Defense (GMD) interceptors, now being deployed in Alaska and California. These are the first stage of a very rudimentary, national missile defense. The recent test failures have been well publicized, but while the Missile Defense Agency (MDA) claims that the problems that caused the failures have been identified, they are reluctant to announce when they plan to resume testing. The GMD interceptors could be modified to attack low orbiting enemy satellites.

| Since the early 1990s, there has been almost no work done on space-based missile defense systems and, according to recent reports, the MDA does not plan to ask for any money before 2008. |

Traditionally, it has been the prospect of America putting antiballistic missile weapons into orbit that has most excited the left, both internationally and at home. In March 1983, when Ronald Reagan called on the scientific community to make nuclear weapons “impotent and obsolete,” everyone leaped to the conclusion that he was talking about space weapons, and Ted Kennedy immediately called the whole idea “Star Wars.” In fact, Reagan was thinking primarily about space systems, but was mostly interested in beginning the process of technology development. He was not wedded to any one concept or system. His Strategic Defense Initiative began as an effort to answer the question: could America be defended from a Soviet missile attack and what would it take to do so?

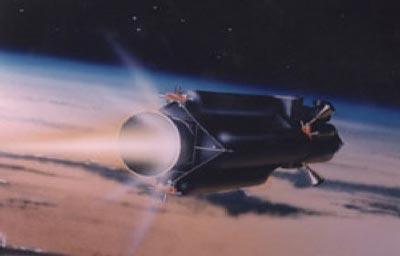

In 1991, under then-Defense Secretary Dick Cheney, the DoD announced that it was planning to deploy something called Global Protection Against Limited Strikes (GPALS). This was to have consisted of at least 2000 orbiting Brilliant Pebbles—small satellites with a heat seeking guidance system, designed to hit enemy missiles in the boost phase. It was based on the military principle that it’s easier to be “up” and shoot “down,” a phenomenon well understood by nine-year-old boys equipped with water balloons. The whole project, however, was canceled by Bill Clinton’s Secretary of Defense, Les Aspin, with the words, “I’m taking the stars out of Star Wars.”

Since then, there has been almost no work done on space-based missile defense systems and, according to recent reports, the MDA does not plan to ask for any money before 2008. Under current plans, the Pentagon will not even think about deploying any sort of “son of Brilliant Pebbles” until around 2015. Instead, they are working on a ground-based system, called the Kinetic Energy Interceptor (KEI): a missile that would only be launched after an enemy missile has left its silo or launch pad, and would then chase until hopefully hitting and destroying it; that is, being “down” and shooting “up.” Not only that, but the KEI’s would have to be based in nations near the sites from which enemy missiles might be launched. This gives those nations where these interceptors would be based an effective veto over whether the US could or could not defend itself.

The latest addition to the array of possible space weapons are the so called “space strike weapons.” The most advanced of these space strike weapons is the Common Aero Vehicle (CAV). Work on the CAV began during the Clinton administration. This effort was mostly confined to a few “blue sky” studies, including the 2002 Rand publication, “Space Weapons—Earth Wars.” Among other things, this study concluded that these weapons would not be effective against “runways, deeply buried bunkers, bridges and long low buildings.” According to this study, a notional weapon weighing 100 kilograms would only be able to penetrate 1.5 meters of steel, or 3 meters of clay and stone—hardly enough to reach the deep bunkers we believe the Iranians have built to hide their nuclear weapon development facilities. In spite of their capability to hit targets at velocities of anywhere from 2 to 10 kilometers a second, it would take a very large weapon indeed, or several smaller ones, to hit the type of deeply-buried targets expected to exist in Iran and North Korea.

| After all, why not fight wars in space? There’s lots of room there and not a lot of civilians to get in the way. |

This has excited foes like Center for Defense Information and the New York Times. The CDI’s space expert, Theresa Hitchens, has been a leading lobbyist against all sorts of space weapons for the last few years. Since the DoD is moving with glacial bureaucratic slowness towards a possible decision to begin work on space-based missile defense weapons, let alone on “Rods from God,” the CDI’s recent effort may have more to do with fundraising than with the actual politics of military strategy or procurement. The trigger for this burst of activity was the request by the DoD that the new space policy consider the need to actively defend US satellites.

This issue, rather than “Rods from God,” is the real subject of the current debate inside the administration. There is an urgent need to equip the next generation of major American military satellites with effective self-defense systems. These could include low-power solid-state lasers that could blind, or even fry, enemy ASAT weapons or, even small, kinetic, last-ditch defense systems analogous to the Navy’s Phalanx rapid-fire guns. There is even a possibility that high-powered microwave weapons might be deployed to defend large US spacecraft, but this would present a difficult problem since it would create a electromagnetic shock that might damage the spacecraft which the system was trying to protect.

If built and deployed, these weapons would indeed constitute unilateral “space weaponization.” The opposition believes that, like virginity, space would somehow lose its purity once orbital weapons of any sort were deployed. Officials in China, Russia, and France speak as if their national security depends on the continued defenselessness of America’s military space infrastructure.

The nature of space technology, and of space itself, as the ultimate high ground, means that there will be weapons, and future battles, outside Earth’s atmosphere. No matter what actually happens, it is almost certain that some will find a way to blame America. Therefore, any decision regarding the building of any space warfare system should be made strictly on the basis of military utility. Since no argument or foreign threat will likely change the minds of those who are against space weaponization, any change in US space policy, no matter how mild or hedged with caveats, will be portrayed as opening the doors of hell. Rather, under current circumstances, President Bush should authorize the pursuit of more and better space assets, including weapons, and Donald Rumsfeld should be pushing the Air Force to radically improve the way it designs and builds all its space systems.

After all, why not fight wars in space? There’s lots of room there and not a lot of civilians to get in the way.