Reality is underrated: Fox’s “Stars on Mars” takes offby Dwayne A. Day

|

| I won’t declare that it is great, riveting television, but it is watchable, doesn’t take itself too seriously, and doesn’t insult the viewers’ intelligence. |

My article was primarily about the long and unsuccessful history of space-themed reality shows. By my count, “Stars on Mars” is only the second space-themed reality show to reach the air (or should we say the stream?) after a string of attempts over two decades—a dozen or more proposed shows that we know about. “Stars on Mars” does not involve sending anybody to space, let alone Mars, which is probably why it succeeded in getting funded. Reality shows depend upon being cheaper than scripted television, and all the previous failed efforts proposed having an actual spaceflight (possibly only suborbital) as the prize. That would cost millions of dollars, making the show too expensive to fund (see “Red planet reality,” The Space Review, May 30, 2023.) “Stars on Mars” doesn’t have a spaceflight prize. Indeed, there is no indication of any prize at all other than being declared “the greatest star in the galaxy,” bragging rights that probably won’t get the winner a good table at a Los Angeles restaurant.

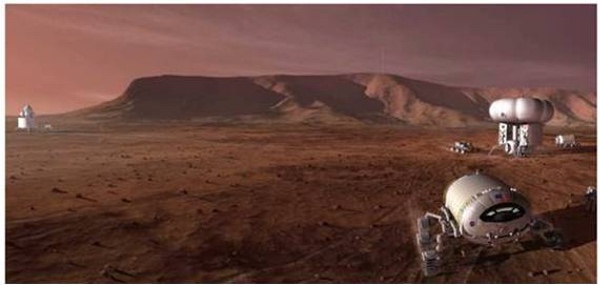

TNASA-produced art of a human mission to Mars shows terrain nearly identical to the Coober Pedy area of Australia. This location has been the site where several movies, including at least one about Mars, have been filmed. (credit: NASA) |

The concept is simple: an initial group of 12 people is in a habitat on Mars. Things go wrong and they have to solve them as a team. Underperforming on a mission gets you sent home. The celebrities are, of course, not on Mars. They’re in the Australian outback, an area known as Coober Pedy that is bizarre and spectacular, and has been the filming site of several movies, usually those featuring either a blasted hellscape or Mars (but I repeat myself). Like a lot of Australia more than a few kilometers from the ocean, it is also rather hostile to human life, and many residents there live under ground. The show was apparently filmed relatively recently—it was supposed to last 24 days, and since it premiered in early June filming should be over by now. Filming in Australia’s winter was a necessity, because otherwise the actors would have died in their heavy simulated spacesuits, which one actor said weigh 27 kilograms.

The producers took the premise of the 2015 movie The Martian and then stretched it out into multiple episodes. Andy Weir, who wrote the book that the movie is based upon, should probably get a royalty check for this, because a number of his ideas, like a sandstorm knocking out communications and a fire destroying the food supply and requiring the astronauts to grow potatoes in human waste, are used in the show as the mission challenges that the crewmembers have to solve. Surprisingly, this premise works. None of it is very scientifically accurate—Martian sandstorms won’t knock over radio towers, and we don’t know if there’s an alien fungus on Mars that has to be burned out of caves—but neither was The Martian. Several years ago, I talked to a prominent NASA astronaut who was rather annoyed at the movie’s reputation for technical accuracy, because he thought that it was massively wrong in many ways. You have to suspend your disbelief a bit more for “Stars on Mars” than for The Martian, but not much.

The show’s premise of a real space mission also extends well to the interpersonal dynamics. They are all part of a team, not individually competing against each other. The celebrities have to work together on at least one mission during each episode, and this usually involves all of the crew except for an elected base commander and a mission specialist, who both stay back in the command center to provide guidance. After returning to the habitation module, the crewmembers who did the best are declared “mission critical.” The bottom three performers are then required to plead their case as to why they should not be sent home. The missions are timed, and if the crewmembers fail to accomplish the mission before the clock runs out, then even the base commander can be sent home. Teamwork is crucial. Leadership is just as important, and culpable, as the people performing the job.

| “Stars on Mars” also looks great. The interior of the hab and the exterior terrain are filmed in vivid colors. It may not be theater-quality, but it doesn’t look cheap or silly. |

So far, the decisions to send crewmembers home have made sense. Of course, reality shows are often scripted to some extent, and they are certainly edited, so the producers were not going to show us somebody getting booted who really deserved to stay. The first person sent home didn’t work hard—or at all—on a mission. During a later episode, another slightly eccentric crewmember serving as base commander provided lots of positive encouragement during a mission but made a critical mistake by picking the wrong person to accomplish a task. The celebrity who failed the mission of retrieving water for the habitat did not get the boot—the commander who picked her did. Another celebrity was sent home because, by his own admission, he lacked focus; his mind was back on Earth, or more accurately, Los Angeles, where he had left a scandal on another reality show. Two others no longer wanted to be there: one missed his family and another found the missions too difficult. If you don’t want to participate—if you don’t want to “be on Mars”—you’re not going to do a good job.

To the show’s credit, all of the choices on who stayed and who went were consistent with what you would expect and want during a real space mission—only the most committed and hard-working people belong, and the rest are liabilities. A commander who makes choices based upon who they like rather than who is most capable is a lousy commander. A crewmember who doesn’t always do their best during an important task that the rest of them depend upon is a danger to their safety. Strength can be an asset unless the strong crewman is unmotivated. Only people who want to be there should be there. The show is logically consistent, but also consistent with the requirements of a real space mission.

“Stars on Mars” also looks great. The interior of the hab and the exterior terrain are filmed in vivid colors. It may not be theater-quality, but it doesn’t look cheap or silly. Again, The Martian clearly served as the show’s inspiration, as did other Mars-themed television series of recent years. There are indications that even some of NASA’s artwork of astronauts on Mars is based upon the Coober Pedy terrain, so it feels like Mars, because artists and movie directors have been using it as Mars for a long time now.

“Stars on Mars” started with twelve celebrities, eliminating one or more per episode. The show is filmed in the Australian outback. (credit: Fox Television) |

The biggest weakness of “Stars on Mars” is the choice of celebrities. None of them are very interesting. We are lucky that nobody is overly dramatic, selfish, manipulative, or downright evil: common tropes of reality TV. But so far, none of them is the kind of person you would want to hang out with or spend time in a closed living space with—not because they are annoying, but because they are dull. At least some of that seems to be the show’s fault, because so far it has not delved into their backgrounds or who they really are beyond a very superficial level—something that is difficult to do with such a large cast.

Many of the celebrities have been in the news for some unflattering reason, and there have been slight hints that maybe there is more depth to them than the tabloid reporting has indicated. Ronda Rousey, a former wrestler, clearly likes to exercise, but appears less tough and a bit more fragile than you would expect, missing the child she left back home. Actress Ariel Winter, despite being portrayed as a bit of a dimwit in the first episode, has demonstrated that she has good observational skills and indicated that she really wanted to be there, in part to prove herself—her brief discussion of being forced into acting while very young explains why she wants to control her own narrative. Disgraced cyclist Lance Armstrong so far comes across as a bit of a curmudgeonly jerk who doesn’t really like anybody, is more of a loner than a team player, but is always eager for a challenge. Are these their real personalities or selective editing? It doesn’t seem to matter all that much. William Shatner appears for about one minute per show, and none of his egotistical and self-effacing goofy charm is present either.

In a twist (you knew there would be a twist, right?) after booting five of the 12 celebrities off Mars, in episode five we are going to get four new people. Who are they? We don’t know yet. Maybe they’ll inject a bit more excitement into the show. Maybe they’re all Klingons and will try to take over the base. Unfortunately, Captain Kirk is still back on Earth, phoning it in.

Human exploration of Mars by now seems to be a consistent, if niche, part of our popular culture, a mixture of entertainment, reality, and fantasy, with very fuzzy lines between all of them. There have been television shows and many movies about explorers on Mars in the last two decades alone, and there is clearly a portion of the American public that is interested in this topic and willing to pay for and consume the entertainment.

| Much of space enthusiasm is indistinguishable from entertainment, so it’s not surprising that instead of real Mars missions, we’re going to keep getting shows that pretend that humans are on Mars. |

But Mars enthusiasm itself has been a form of entertainment for a few decades now, based upon short and selective memories (see “Is a dream a lie if it don’t come true?” The Space Review, May 1, 2017.) Many Mars enthusiasts have mostly forgotten that in the early 1990s, Bob Zubrin was going around talking about Mars Direct and saying it would be easy to put humans on Mars in a decade or so. They’ve probably forgotten that in 2014 the group Mars One was making big promises about a Mars base using the Red Dragon lander. Mars One gained a tremendous amount of news coverage—some serious, some mocking—but then it imploded a few months later, and Red Dragon never got built. And in 2016–2017, Elon Musk was predicting that a really big rocket would be putting humans on Mars by 2024, and many adulating fans took him at his word (one of them asked to go up on stage and give him a good-luck kiss). One wonders if, over half a decade later, the Mars enthusiasts are just as excited about Starship delivering cargo to low Earth orbit and maybe, someday, landing on the Moon, as opposed to settling the Red Planet. But just like the failure of doomsday to occur can often reinvigorate a doomsday cult, maybe the failure of a Mars mission to materialize can reinvigorate the belief that a Mars mission is only slightly delayed. (See “Elon Musk’s road to Mars”, The Space Review, October 3, 2016, and “Mars mission sequels”, The Space Review, October 2, 2017)

Much of space enthusiasm is indistinguishable from entertainment, so it’s not surprising that instead of real Mars missions, we’re going to keep getting shows that pretend that humans are on Mars. And it’s no surprise that the history of space-themed reality television shows essentially mirrors our own reality: take the actual spaceflight out of it and just pretend you’re in space.

With the Hollywood writers’ strike still going on and movies and TV shows being delayed, we could end up with more shows like this. That’s not what I, or really anybody, wants. But for now, “Stars on Mars” is a reasonably fun bit of summer reality sci-fi fluff.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.