Honoring and dishonoring the dead in outer spaceHow a Virgin Galactic spaceflight sparked a scandal in anthropologyby Deana L. Weibel

|

| Hominin fossils were new, but the desire to take significant objects into space was very familiar. |

The fossil specimens had been chosen by Dr. Lee Berger, a “flamboyant” paleoanthropologist (Horn 2023) well known for his enjoyment of attention and pursuit of publicity. The first Homo naledi specimens were found during the Rising Star Expedition, led by Berger in 2013. Although the first examples of Australopithecus were found much earlier, in 1974, Berger discovered a specific subtype, Australopithecus sediba in a 2008 expedition. His son Matthew is actually credited with finding the first of these fossils, the very collarbone fragment taken into space by Nash. The elder Berger approved taking these hominin specimens into space (hominin refers to us humans as well as all of our evolutionary ancestors who walked bipedally), but in wider anthropological circles, when the unusual spaceflight became public, it struck many anthropologists as disrespectful, distasteful, and ethically suspect.

A miniature Torah that traveled in space with astronaut Jeff Hoffman at Congregation Or Ami in Houston. (credit: Deana Weibel) |

Of ethics and objects

This distaste did not surprise me. Although I am not a paleoanthropologist, as an anthropologist in a “four-field” department that includes archaeology, physical anthropology, linguistic anthropology, and my own subfield, cultural anthropology, I am familiar with the work undertaken by my colleagues and the kinds of ethical considerations involved. My first reaction personally, however, was not to be shocked by the ethical considerations, but instead to wonder what on Earth had motivated Nash or Berger to take hominin fossils into space in the first place. I am an anthropologist of religion who studies the religious understandings of outer space and have talked to astronauts about the personal items they take into space. Hominin fossils were new, but the desire to take significant objects into space was very familiar.

I have studied pilgrimage for many decades and it’s always interesting to see what objects people bring with them to sacred places. Sometimes a holy place was thought to add a layer of meaning or even infuse an object with a kind of energy. Some pilgrims would rest a keepsake against a sacred statue to let it “absorb” that sacredness, and I knew of a family in Chimayó, New Mexico, who left an heirloom crucifix at the local shrine for weeks. Outer space may or may not be sacred, but many astronauts follow the pilgrimage pattern, taking personal items, including religious jewelry or other objects with them: once an object is “space flown” it seems to gain particular significance. One of the astronauts I interviewed took a series of crucifix necklaces into space and drew a comparison between space-flown objects and objects that have been blessed. Congregation Or Ami in Houston displays a miniature Torah that traveled in space with astronaut Jeff Hoffman (Tenorio et al. 2016). The way the object looks or feels obviously doesn’t change, but the meaning of the object, its history, is somehow transformed.

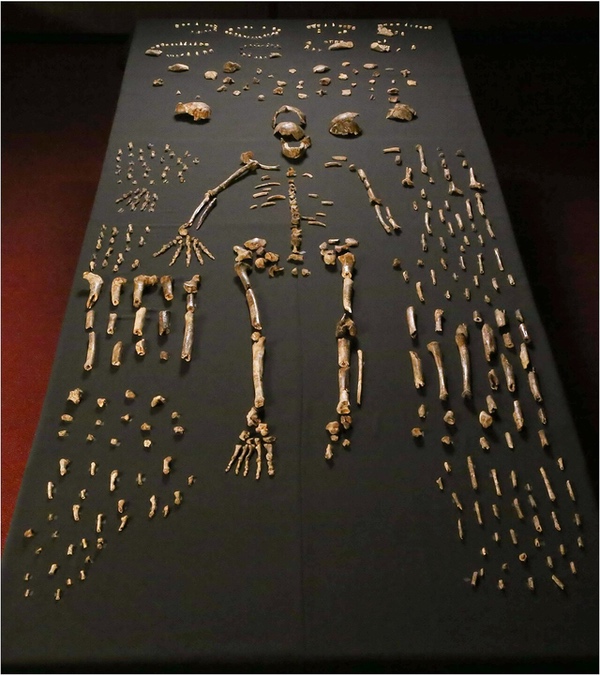

Skeletal fossil specimens of Homo naledi. (credit: By Lee Roger Berger research team - http://elifesciences.org/content/4/e09560) |

Fossils as symbols

While I don't approve of significant and irreplaceable scientific specimens being taken into outer space, what I understand from my research about the different meanings involved in taking personal objects on space missions or pilgrimages makes me more understanding. When Nash and Berger decided to bring the fossils on the VSS Unity flight there may have been motivations beyond mere publicity. It is not unusual to take an object with existing significance and overlay it ritualistically with additional significance by bringing it to a sacred site. Pilgrims (and astronauts) do this all the time with family keepsakes, wedding rings, rosaries, and other objects already infused with meaning. There is something wondrous about being able to bring the collarbone of an ancient human ancestor up into space, a symbolic fusion of the past and the future that does not have scientific bearing but at least follows a certain spiritual logic.

Interestingly, this symbolic significance appears to have been enough for Berger to have been granted a permit by the South African Heritage Resources Agency (SAHRA) to allow Nash to take the hominin remains into space. In his proposal description, Berger writes, “This would make these fossils the first extinct humans into space and act as a sign of respect by humanity to our African ancestors who gave us the technology, skills and mind that allows this perhaps greatest expression of human technological achievement—the exploration of space” (“Heritage Cases” 2023). Despite Berger’s statement, it is a stretch to refer to fossilized bones from Homo naledi and Australopithecus sediba as “humans”: the species were not human but are theorized to have been possible ancestral species to humans.

Attendees of a Celestis memorial ceremony at Spaceport America. (credit: Deana Weibel) |

Spaceflight as a mortuary ritual

It may also seem strange to refer to pieces of individuals, such as part of a thumb or collarbone, as “humans.” I’ve done research, however, indicating that even a few ounces of a person’s cremated remains become a “human” under the right circumstances, specifically in the little-studied mortuary practice of sending human remains on rocket launches. I undertook a recent ethnographic field study, in November 2022, to Las Cruces, New Mexico, for a memorial service in preparation for such a spaceflight. The planned mission would take 118 “passengers” (small metal containers holding between one and eight ounces of a person’s cremated remains) into space and return them again to Earth via a suborbital flight from Spaceport America. Organizing this space trip was a company called Celestis, a business that conducts memorials for the dead that involve sending “symbolic portions” of them into outer space, sometimes on a suborbital flight (the ashes are returned to family or friends afterward), sometimes into orbit (your loved one’s ashes can be tracked from your cell phone), and sometimes into deep space, on an endless journey into infinity. Celestis doesn’t use its own dedicated rockets but purchases payload space on rockets of various types and sizes that are scheduled to be launched for other reasons.

| Several grams of a person’s ashes could somehow retain that person’s identity and essence, at least in the loving imaginations of their friends and families. |

Although the particular launch I had intended to watch was ultimately canceled and its “passengers” re-booked onto other flights, the language used in the memorial and the leadup to the scheduled launch was fascinating. The memorial service, which was also livestreamed, was more complicated than many funerals, with a poetry reading, live music (including a rendition of “Amazing Grace” on bagpipes), heartfelt speeches by Celestis executives, a eulogy by a retired astronaut (the astronaut at one point told the mourners that he believed those who loved outer space would be able to explore the universe after death), and tearful statements by family members who celebrated their deceased loved ones and explained that sending their ashes into space was fulfilling a promise, accomplishing a life goal, or was otherwise meaningful.

A slideshow played during the service, displaying a picture of each “passenger” and a phrase or quotation that had been chosen by the deceased person (many had arranged beforehand to be flown after their deaths) or by the family. Examples included “Enjoy the views nana,” “Man’s role is to take flight into the universe,” “My Search For The Ethereal World Continues,” “Your wish has come true!” and “Climbing The Stairway To Heaven.”

Three things were clear about the memorial service. One, outer space was frequently presented in an otherworldly, quasi-supernatural way, similar to the concept of “heaven.” Two, going into space had been a dream held by many of the “passengers,” one that could still be fulfilled after death. Three, several grams of a person’s ashes could somehow retain that person’s identity and essence, at least in the loving imaginations of their friends and families.

The most striking example of the last phenomenon was when a woman came up to the dais to speak about a family member who had loved space, but who had had a significant disability that would not have allowed him to ever fly. She talked of his love of space, passion for NASA, and enthusiasm for learning more about the solar system and universe. When his slide came up in the rotation, it referred to him as the first astronaut with his particular disability to ever fly in space. I was struck by this because it implied that this “passenger’s” cremated remains were still a person, would be considered an “astronaut” when they went into space, and that they somehow retained the person’s disability. If the “passenger” was disabled in life, and this disability was a significant part of his identity, then the several ounces of his cremated remains to be sent into space would continue to hold that identity.

The author at Spaceport America. (credit: Deana Weibel) |

Human remains remaining human

The idea that a person’s remains can still retain their “humanness,” including some sense of conscious awareness, is not uncommon in mortuary rituals and customs for interacting socially with the dead. An article by Pamela Roberts on American cremation practices gives several examples of cremated remains being kept by loved ones and made to act almost as a living person. For instance, she writes, “In the first year after his death, another participant’s husband’s ashes were on the living room shelf, but she would bring them down for special occasions; for the Super Bowl, she dressed the ashes in a baby t-shirt from his favorite football team and she and her brother talked to him throughout the game” (Roberts 2011). If cremated remains can be imagined to watch the Super Bowl, they can certainly be imagined to appreciate spaceflight. And if an entire company is based on sending the remains of contemporary Homo sapiens into outer space, is it so strange if Homo naledi and Australopithecus sediba are sent into space as well?

An idea that the hominin remains functioned to some degree as living people seems to be part of why they were taken into space. Kristina Killgrove describes the motivations of Nash and Berger, writing, “Lee Berger…noted that ‘the journey of these fossils into space represents humankind's appreciation of the contribution of all of humanity's ancestors and our ancient relatives,’ while Matthew Berger speculated that these hominins ‘never could have dreamed while alive of taking such an incredible journey as ambassadors of all of humankind's ancestors.’” The men’s statements echo the ideas presented in Celestis memorial services, reinforcing the notions that going into space is somehow a transcendental experience, that remains of dead persons are somehow aware of what is happening when they do go into space, and that going into space is ultimately transformative, conveying honor in some way on those once-living beings whose bodies contained that thumb bone and that collar bone once upon a time in our planet’s distant prehistory.

Anthropology’s troubled history with the dead

While Celestis customers can confidently speak for their dead, however, we have no way of knowing what members of the Australopithecus sediba and Homo naledi species would have thought about space. We know something about their bodies, but we know nothing about their minds. They are nearly as alien to us as an extraterrestrial being would be. True respect for the prehistoric dead involves the recognition that their ideas and ways of life aren’t available to contemporary researchers and that it is best to err on the side of caution.

| The “journey” may have been intended as a show of respect, but it made unwarranted assumptions about what our “ancestors and our ancient relatives” would have consented to (while simultaneously exposing these important fossils to potential destruction without a scientific rationale to do so.) |

Anthropology is still learning this lesson. There is a long history of anthropologists (and others) misappropriating the dead. While the graveyards of European settler communities in the United States have largely remained undisturbed, many universities and museums until very recently considered burials of indigenous populations to be legitimate sites to excavate and research. Scholars would often carry away, study, store, and display human remains and important ritual objects with little thought to what would have been the preferences of the dead. In 1990, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was passed to prohibit these practices and return mortuary items and remains to their rightful heirs. The process of repatriating human bones and other objects has taken decades and is still underway (for a good overview, see Nash and Colwell 2020). Other countries with colonial heritage, handle similar situations on their own terms. Australia, for instance, has a repatriation plan (Indigenous Repatriation 2019), while South African activists appear to be initiating a similar approach (Wild 2019).

Most anthropologists have become sensitive to the damage caused by the discipline’s history, and while fossils of ancient hominin species like Australopithecus sediba and Homo naledi are not covered by repatriation laws, a growing disciplinary respect for the dead has developed in recent decades. This is perhaps why Nash’s decision to take the hominin remains into space, and (especially) paleoanthropologist Berger’s role in this plan, were met with such a backlash among anthropologists (see, for instance this X (formerly Twitter) thread by physical anthropologist Alessio Vaneziano). Berger, at least, might have known better.

Nevertheless, in a statement published by the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. Berger justified the act, writing, “The journey of these fossils into space represents humankind’s appreciation of the contribution of all of humanity’s ancestors and our ancient relatives. Without their invention of technologies such as fire and tools, and their contribution to the evolution of the contemporary human mind, such extraordinary endeavors as spaceflight would not have happened” (University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 2023). The “journey” may have been intended as a show of respect, but it made unwarranted assumptions about what our “ancestors and our ancient relatives” would have consented to (while simultaneously exposing these important fossils to potential destruction without a scientific rationale to do so.)

A NASA mission shows a different way to honor an ancestor of humanity. (credit: NASA) |

A more enlightened approach

There are perhaps better ways to honor our distant ancestors as we explore space. In 1974, paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson and his student Tom Gray found skeletal remains in Hadar, Ethiopia, and soon realized they had uncovered a previously unknown hominin species. The female skeleton they found was an Australopithecus afarensis, nicknamed “Lucy” after the Beatles’ song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds.” She walked upright, and although her species has not been proven to be ancestral to Homo sapiens, “Lucy” has taken a symbolic role as a mother figure for all humankind.

| Lucy’s mission patch includes a graphic representation of its namesake hominin’s skeletal remains, bringing the name and image of this ancient being into outer space, while leaving her remains safely on Earth. |

While the idea to take fossilized remains of a different Australopithecus species into space this summer may have seemed innovative to Berger and Nash, the Australopithecus “Lucy” has already been honored in space exploration, not by taking any of her priceless bones into space, but by giving her name to a NASA spacecraft. The space probe known as “Lucy” is currently enroute to our solar system’s asteroid belt on a mission to better understand both main belt asteroids and Jupiter trojan asteroids. It was named both for the spacecraft’s Thermal Emission Spectrometer, which contains diamonds, and for a flight path that will take it past an asteroid named for Australopithecus afarensis discoverer, Donald Johanson (Dunn 2021).

The scientific value and innovation of the Lucy mission is unquestionable and deeply valuable, as it will exponentially increase our species’ understanding of asteroids. Its organizers honored our species’ symbolic mother figure while remaining ethical: Lucy’s mission patch includes a graphic representation of its namesake hominin’s skeletal remains, bringing the name and image of this ancient being into outer space, while leaving her remains safely on Earth and in her home territory, preserved and protected in the National Museum of Ethiopia.

Works Cited

AHEADmeeting. “Why Does Sending Hominin Specimens into Space Raise so Much Indignation? A Short Thread with Some of the Reasons That Appear from Reading People’s Opinions. (1/5)Read and Comment to Add Your Thoughts!#humanevolution #paleoanth #bioanth #BioArch #hominins #ahead23 Pic.Twitter.Com/GpzklSoyLm.” Twitter, September 11, 2023.

Devitt, Terry. “Homo naledi: Fossil Trove Adds a New Limb to Human Family Tree.” Homo naledi: Fossil Trove Adds a New Limb to Human Family Tree. Accessed September 16, 2023.

Dunn, Marcia. “NASA’s Asteroid Hunter Lucy Soars into the Sky - with Diamonds.” Associated Press (via Los Angeles Times), October 16, 2021.

“Heritage Cases.” SAHRA. Accessed September 22, 2023.

Horn, Jan. “Homo naledi: Who Are These Strange Star Children?” Vrye Weekblad, June 9, 2023.

“Indigenous Repatriation.” Indigenous Repatriation | Office for the Arts, December 20, 2019.

Killgrove, Kristina. “‘I Am Horrified’: Archaeologists Are Fuming over Ancient Human Relative Remains Sent to Edge of Space.” LiveScience, September 12, 2023.

“Lucy’s Story.” Institute of Human Origins. Accessed September 16, 2023.

Nash, Stephen E., and Chip Colwell. “Nagpra at 30: The Effects of Repatriation.” Annual Review of Anthropology 49, no. 1 (2020): 225–39.

Roberts, Pamela. “What Now? Cremation without Tradition.” OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying 62, no. 1 (2011): 1–30.

Tenorio, Rich, Lazar Berman, Luke Tress, David Horovitz, Emanuel Fabian, ToI Staff, Ron Kampeas, et al. “Space Torah: When the Creation Story Flew Back into the Firmament.” The Times of Israel, December 30, 2016.

The University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. “First Fossils of Ancient Human Relatives Journey to Space.” University of the Witwatersrand. Accessed September 22, 2023.

Wild, Sarah. “In South Africa, a Return of Stolen Indigenous Remains.” Undark Magazine, December 10, 2019.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.