Crisis in space: The 1973 Yom Kippur War and “crisis reconnaissance”by Dwayne A. Day

|

Launch of a top secret GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance mission in the early 1970s. These satellites returned their film to Earth in reentry vehicles, which limited how quickly their images could reach decision makers. In 1971, senior DoD and intelligence officials determined that this capability was sufficient in event of a crisis, a decision that some later regretted when the Middle East again erupted into war. (credit: USAF via Peter Hunter) |

During the 1960s there were several major events that highlighted the value and need for satellite imagery capable of providing what came to be known as “crisis reconnaissance” and “crisis response.” The Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962 had involved the use of both high-altitude U-2 reconnaissance photographs and low-level photos taken by Navy RF-8 Crusader jets, all obtained at considerable risk to their pilots. The June 1967 “Six Day War” in the Middle East and the August 1968 Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia had both occurred at times when American reconnaissance satellites could have provided intelligence if the timing had been right, but were unable to do so.

| During the 1960s there were several major events that highlighted the value and need for satellite imagery capable of providing what came to be known as “crisis reconnaissance” and “crisis response.” |

Throughout the decade there were proposals and discussions within the US reconnaissance community about improving the timeliness of satellite photography. Because American satellites used film, these studies assessed ways of launching satellites faster and quickly bringing their film back to Earth for analysis. But by 1969, the Executive Committee (ExCom) of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), which developed and operated intelligence satellites, rejected the development of a dedicated crisis reconnaissance satellite. The ExCom believed that overall strategic assessment of the Soviet Union was higher priority than crisis reconnaissance, and the technology for the latter was still immature.[1]

The issue reemerged again in 1970 as tensions between Israel and its Arab neighbors threatened to flare into war, and a rickety ceasefire was declared between the parties. Diplomats in the US State Department were interested in a satellite that could provide near-real-time monitoring of the ceasefire, especially as it neared its expiration date. By January 1971, their pressure led to renewed study of options for developing such a capability in the near-term, including satellites equipped with multiple reentry vehicles that could send their film down to Earth during a crisis while the satellite remained in orbit. But many in the intelligence community were interested in what they considered a more attractive method of providing timely photographic reconnaissance of crisis areas—meaning returning imagery within 24 hours or less of taking a photo.

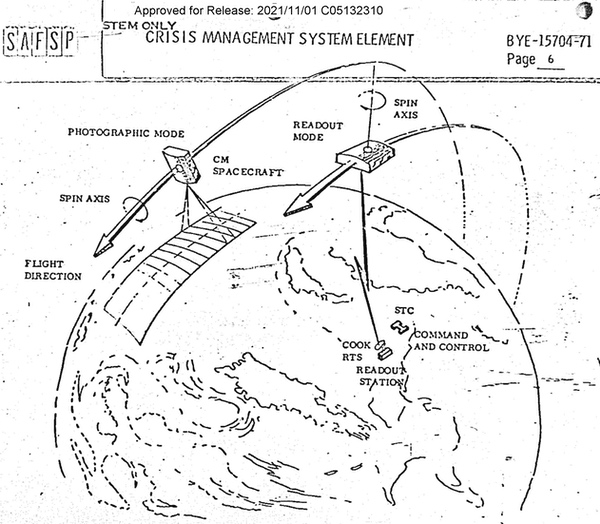

The SPIN SCAN satellite was studied from 1967-1971 and could have served in a crisis-reconnaissance role, launched during an international crisis to return imagery to the ground in under 24 hours. If it had been approved in April 1971, it could have been available in time for the October 1973 Yom Kippur War. (credit: NRO) |

Starting in 1967, the NRO had funded contractor studies of a small reconnaissance satellite named SPIN SCAN to be carried into orbit on the side of a much larger reconnaissance satellite named the HEXAGON.

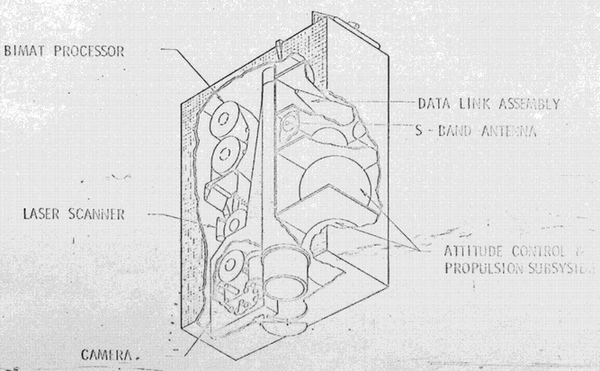

Approximately the size of a large refrigerator, and shaped like a deck of cards, SPIN SCAN would be spin-stabilized at 29 rpm, with a panoramic camera mounted normal to the spin axis. It would be 1.2 by 2.1 by 0.6 meters (4 by 7 by 2 feet) During photography, the spin axis would be parallel to the Earth’s surface, scanning a swath of 333 kilometers (180 nautical miles) and about nine kilometers (five nautical miles) wide, providing ground resolution up to one meter, good enough to identify vehicles such as tanks and artillery. After passage over the “crisis area,” the spin axis would be pointed toward the sun to provide maximum exposure of solar cells on the broad side of the satellite and reduce drag by orienting the satellite to fly “edge-on” at perigee when no photography would be taken. Exposed film would be developed on board with the bimat process used for the earlier Samos reconnaissance satellite and NASA’s Lunar Orbiter, and then the developed film would be scanned by a laser scanner and the video transmitted to the tracking station where the pictures would be reconstructed with a laser recorder.[2] SPIN SCAN was intended to stay dormant in orbit for up to a year and operate for approximately a month, so it could have been activated in orbit only when necessary.

| If SPIN SCAN had been approved in January 1971, or more likely April 1971 when the NRO’s ExCom specifically met to review possible interim crisis reconnaissance satellites, the intelligence during the Yom Kippur War could have been much more substantive. |

By 1971, the final SPIN SCAN design would have weighed 726 kilograms (1,600 pounds), too big for the HEXAGON, and instead would have required a converted Atlas ICBM known as the Atlas F. It was selected over the lighter versions based on image quality, coverage, and ability to select the desired orbital inclination. It would have been capable of operating in an orbit of 167 by 389 kilometers (90 by 210 nautical miles) for a month or more, providing 0.76- to 0.91-meter (2.5- to 3-foot) ground resolution. This satellite’s mass was too high to launch more than one on an Atlas F rocket and an earlier concept of placing several in orbit on the same launch to improve survivability against Soviet anti-satellite weapons was not possible. The Atlas could be kept on ready-alert at Vandenberg Air Force Base, able to be launched into orbit with only a few hours’ notice.

SPIN SCAN was studied by four different contractors over several years, who proposed different-sized vehicles with cameras of varying focal length and satellites with different capabilities. But even after the proposal was rejected by the NRO ExCom in 1969, the concept remained alive, and reemerged in 1970 when the State Department became concerned about monitoring the Middle East ceasefire. By April 1971, SPIN SCAN was the leading contender to provide an “interim” crisis reconnaissance capability until a much more capable system became available by 1975 or 1976.

SPIN SCAN would have developed its film onboard the satellite and scanned it with a laser, beaming imagery down when over a ground station in the United States. The images would have been of sufficient quality to identify vehicles. (credit: NRO) |

If SPIN SCAN had been approved in January 1971, or more likely April 1971 when the NRO’s ExCom specifically met to review possible interim crisis reconnaissance satellites, the intelligence during the Yom Kippur War (also known as the Ramadan War, the October War, the 1973 Arab-Israeli War, or the Fourth Arab-Israeli War) could have been much more substantive. The SPIN SCAN contractors estimated that the first demonstration satellite could be made ready by 23 months from go-ahead, and the second by 26 months. Assuming an April 1971 go-ahead decision, and three months to make a contractor selection, it is entirely feasible that a SPIN SCAN satellite could have been built and even tested by summer 1973, with a second also possibly available by the October 1973 war. Because the war ran from October 6 to 25, there was plenty of time to launch a crisis response satellite to provide imagery, if one had been available.

This schedule assumes no program slips. But SPIN SCAN was based upon existing technology and the contractor would have been incentivized to deliver on schedule to maximize the value of the satellite until the near-real-time satellite became operational. The one bit of technology that was not completely mature was the laser scanner. Although proven on the ground, it had not yet flown in space. However, there is reason to be confident that one or two SPIN SCAN satellites could have been available by the time of the Yom Kippur War. It certainly was needed.

An Atlas F launch vehicle on its pad at Vandenberg Air Force (now Space Force) Base in California. The Atlas F would have served as the launch vehicle for SPIN SCAN. A converted ICBM, it could be kept on ready-alert at the pad, able to launch with a few hours' notice, ideal for a crisis-reconnaissance satellite. (credit: Peter Hunter) |

In 1971, the NRO’s ExCom had decided to pursue development of a sophisticated near-real-time reconnaissance capability that would be ready by 1976. Without an interim crisis reconnaissance satellite, American officials would have to rely upon the country’s existing GAMBIT and HEXAGON reconnaissance satellites that were launched only a few times a year and returned their exposed film in reentry vehicles only a few times per mission. This film-return technology had severe limitations on the timeliness of when the images would reach Washington.

There were other options, but they were not ideal. The United States operated U-2 reconnaissance aircraft that could have imaged the Middle East, but they were vulnerable to attack by surface-to-air missiles and could not fly in hostile airspace. The United States also had Ryan AQM-91 Firefly drones that had a low radar cross-section. They could image a swath of ground 80 kilometers (43 miles) wide and 3,185 kilometers (1,720 miles) long at .3-meter (1-foot) resolution. They could be launched from a DC-130 Hercules, with mid-air recovery by a helicopter. But by summer 1973 a decision had been made to retire them by the end of September, and it was not clear how they could be operated over hostile airspace.

When it came to providing imagery intelligence over hostile territory, satellites were the only viable solution. A report prepared for the Secretary of Defense in February 1973 stated it succinctly: “Satellite reconnaissance is undoubtedly the single most important tool available to the nation for the detection and assessment of foreign offensive capabilities. Satellites have been the sole means of identifying and locating all Soviet and Chinese offensive missile launchers; virtually all new major weapon system developments have been first identified by overhead collectors.”[3]

In August 1973, the Washington Special Actions Group met. WSAG consisted of senior diplomatic, military, and intelligence officials who addressed major international issues. They were still mostly focused on Vietnam, where American forces had recently withdrawn after the ceasefire. American intelligence had been monitoring supplies going to North Vietnam for indications that they were planning for an offensive. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger, who would soon be appointed as Secretary of State, was very keen to know about satellite reconnaissance capabilities, as demonstrated by a declassified transcript of one of his meetings.

Mr. Kissinger: Our assumption has been that they [North Vietnam] would not start an offensive unless they had a big back-up of supplies. They did not say they would not send civilian supplies.

Admiral Thomas Moorer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: They are getting some by sea also.

Mr. Kissinger: Can we see it?

Adm. Moorer: Probably at Haiphong.

Mr. George Carver [CIA]: We will be lucky if we do, with satellite coverage every seven weeks and with cloud cover and the number of ships in port on any given day.

Mr. Kissinger: Can’t we schedule these satellite flights more frequently?

Mr. Carver: They are not time sensitive.

Adm. Moorer: And we don’t have a spare for crisis situations.

Mr. Kissinger: Why not?

Mr. William Colby, Director of Central Intelligence: We have three a year. We always have a spare.

Mr. Kissinger: Why don’t we have more?

Mr. Colby: Because of the money.

Mr. Kissinger: How much?

Mr. Colby: Each one costs $20 million.

Mr. Kissinger: And we can’t find $20 million in a $17 billion budget?

Mr. William Clements, Deputy Secretary of Defense: This has been very carefully considered and I thought it was agreed that this was adequate.

Mr. Kissinger: In the absence of a crisis.

Mr. Colby: Of course we have the new project. [i.e. the KH-11 KENNEN]

Mr. Kissinger: But that won’t be ready until 1976. That is not related to a crisis situation.

Mr. Colby: We really don’t get that much from satellite photography. We need over-flight.

Mr. Hummel [Department of State]: You mean the U-2R with the new camera?

Mr. Carver: We are just seeing what we can get under the new ground rules.

Mr. Kissinger: I don’t think it’s safe for the U.S. not to have a spare photographic satellite.

Mr. Colby: We can give you coverage anywhere in the world within a 30-day gap.

Mr. Kissinger: But the conditions of an emergency can’t be programmed. I am talking about one vehicle which we could launch in an emergency situation to take a look at it. Suppose there were a Middle East crisis. We don’t have a vehicle to send up.

Mr. Colby: We can give you pictures of the Middle East that are only two or three days old.

Mr. Clements: I think Henry is talking about a short fuse—a situation of a week or ten days.

Mr. Colby: It takes a certain number of days to screw these things together and to get the fuel into them. That’s why we are going for the 1976 solution.

Adm. Moorer: I think it should be tied to DEFCON. When we get a DEFCON and the military starts its moves, I think a satellite should go up.

Mr. Kissinger: But we don’t have anything to put up.

Mr. Colby: Yes, we do—we have a pipeline.

Mr. Clements: If the 30-day period is not acceptable, then we should consider what to do.

Mr. Kissinger: I have nightmares about the danger of someone taking a run at us while we are in the midst of our own cultural revolution—our own emergency situation. (to Mr. Colby) Could you get us a chart of available photo coverage: what we could do in a short time; what we have on standby. Could we get a comprehensive view by the end of the week?[4]

On October 13, 1973, this aircraft flew an 11-hour mission, taking off from central New York and flying to the Middle East, where it overflew the war zone, then returning to its base. The mission, known as GIANT REACH, provided vital reconnaissance photos of the conflict. The only other imagery the United States had during the war was from a GAMBIT-3 reconnaissance satellite mission that returned October 7. (credit: USAF via Paul Crickmore) |

The Middle East was always tense, with minor crises flaring up that seemed to have the potential to turn into full-on war. In September, Israel reportedly shot down 13 Syrian jets in an air battle over the Mediterranean. On October 3, Moscow gave an order to evacuate its diplomatic and military dependents from Egypt.

| When the war started, the United States had a single reconnaissance satellite in orbit, a high-resolution GAMBIT-3, mission 40, launched on September 27. |

On most days of the week, President Richard Nixon received an eyes-only intelligence report known as the President’s Daily Brief, or PDB. It reflected the information that intelligence officials believed was of highest importance for the president to receive. On October 6, the President’s Daily Brief delivered to Nixon stated that a human source had told American intelligence about “information from ‘good sources’ that Egypt and Syria are planning a coordinated attack across the Suez Canal and the Golan Heights before nightfall today.” This was a late addition to the PDB, after the printed report already indicated that tensions were high because of the second day of a Soviet airlift to Egypt and Syria.[5] The PDB was correct, and in hours the Arab tanks began rolling.

Nixon continued receiving updates in his PDB. On October 8, he was informed that Egypt and Syria had made significant gains and that the Israeli leadership was “grim,” but that it seemed that Lebanon was staying out of the war. But days later, the Egyptian and Syrian forces seemed to be making fewer gains, and Jordan’s leader was concerned that he could not continue to stay out of the war if Israel started to move into Syrian territory.[6]

The US intelligence community established a special working group to assess intelligence on the conflict and produce analysis for senior leaders. Intelligence came from multiple sources, including signals intercepts as well as the Israelis themselves, although American officials later concluded that the Israeli reports on the war were overly optimistic. Throughout the conflict, the United States intelligence community paid close attention to Soviet naval forces in the Mediterranean, which were being monitored with signals intercepts—aircraft and naval vessels and submarines—as well as a newly-emerging satellite ocean surveillance capability developed by the National Reconnaissance Office. Several of the PDB reports to Nixon reported on the Soviet naval activity, noting that the number of Soviet ships, including amphibious vessels, had increased.[7]

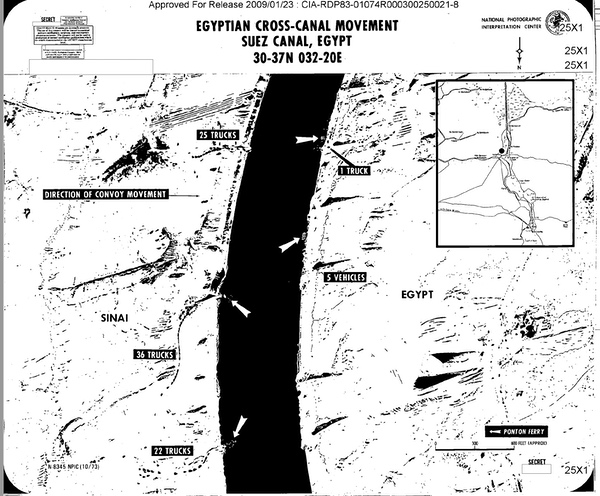

When the war started, the United States had a single reconnaissance satellite in orbit, a high-resolution GAMBIT-3, mission 40, launched on September 27. The GAMBIT-3 was capable of taking photographs over a narrow strip only 9.3 kilometers (5 nautical miles) wide as it flew from north to south, and could not photograph the massive territory covered by the various armies, but its photographs could enable interpreters on the ground to identify specific types of military equipment. The National Reconnaissance Office brought down the GAMBIT’s first reentry vehicle on October 7, several days earlier than planned, apparently to provide intelligence on the war. The satellite stayed in orbit and continued to photograph targets around the world. By late October, its photographic passes over the Middle East were being coordinated with SR-71 missions.[8] But the GAMBIT’s remaining photos stayed onboard the satellite for the duration of the conflict, because its second film reentry vehicle was its last, and once the film was returned, the satellite’s mission was done.

Egyptian forces crossed the Suez Canal early in the war to attack Israeli forces. A USAF SR-71 took this image of one of the crossing points. This is a poor photocopy of the original photograph, which has not been released. (credit: CIA) |

On October 13, the United States Air Force flew an SR-71 Blackbird Mach 3 reconnaissance aircraft over the war zone, a so-called GIANT REACH mission. The mission took off from and returned to Griffiss Air Force Base in central New York state. The total flight time was 11.3 hours involving six aerial refuelings and more than five hours of flight above Mach 3. The aircraft’s imagery was processed and assessed within 48 hours of the mission and provided “extensive” information on the conflict.[9] However, because of the substantial logistics support required to conduct each mission, including multiple refueling tankers, it was not possible to conduct the missions less than three days apart. It also took time to process and interpret the film, so daily reconnaissance of the war zone was impossible.

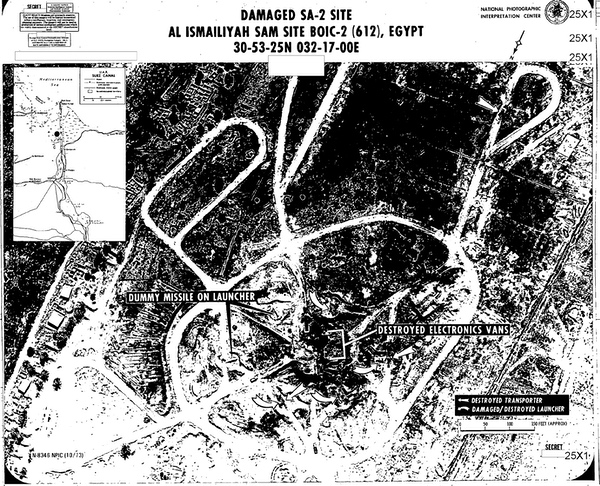

Kissinger remarked on the results of the GIANT REACH intelligence during a WSAG meeting on October 16. Referring to the number of Syrian tanks destroyed in the Golan Heights: “I like our precise intelligence - somewhere between seven and eight hundred!” he quipped.[10] Despite Kissinger’s comment, the few released GIANT REACH imagery reports indicate that the aircraft photographed the war zone in great detail, so much so that it was possible to detect the difference between actual and “dummy” SA-2 and SA-3 surface-to-air missiles among Egyptian forces.

The Soviet Union also had a single reconnaissance satellite in orbit at the beginning of the war, Cosmos 596. It was brought down on October 8, after only six days in space. But the Soviets also had a supply of backup satellites and a rapid response capability. They launched Cosmos 597 on October 6. Shortly after it landed on October 12, the Soviet Union launched Cosmos 598. It was recovered on October 16, the same day the Soviets launched Cosmos 600. It was recovered a week after launch, on October 23. Cosmos 599 had been launched on October 15, but did not observe the conflict zone until the last days of its 13-day mission. On October 20, the Soviet Union launched Cosmos 602 on a nine-day mission. On October 27, the Soviets launched Cosmos 603, also for a 13-day mission, landing a few days before Israel and Egypt signed a peace agreement.

The Soviet reconnaissance capability came to the attention of President Nixon early in the conflict. On October 12, Nixon’s PDB included a statement that “Soviet satellite reconnaissance of the Middle East has increased during the current crisis.” It noted that “Two high-resolution photoreconnaissance satellites currently are in orbit. One of these, which will provide optimum coverage of the Middle East, apparently will be brought down this morning, only six days after it was launched. A low-resolution satellite was brought down early on October 9 after completing one half of its normal 12-day mission. Soviet Elint [electronic intelligence] satellite monitoring of the Middle East has also been at a high level since October 4.”[11]

On October 13, 1973, a USAF SR-71 Blackbird reconnaissance aircraft overflew the war zone and photographed this surface-to-air missile site. This is a poor photocopy of the original photograph, which has not been released. (credit: CIA) |

After their initial success following the surprise attack, the Arab forces began to suffer setbacks as Israeli forces adapted to the Arab tactics, changed from defense to offense, and the Arab armies and air forces took significant losses. The Soviet Union stepped up resupply of Egypt and its allies, but were limited in how quickly this could be done. The war began going against the Arab nations.

| The Soviet Union also had a single reconnaissance satellite in orbit at the beginning of the war, Cosmos 596. But the Soviets also had a supply of backup satellites and a rapid response capability. |

American officials became rather optimistic about Israeli successes, and excited to hear about Soviet equipment that had been seized during Israeli counterattacks. By October 24, the Israelis had captured SA-2, SA-3, and SA-7 missile units, plus a “dud” SA-6 missile. But they were still missing a SA-6 launcher/radar unit, although Israel knew this was at the top of the CIA’s shopping list.[12]

After the tide of the war had turned and Israel was making significant gains, Secretary of State Henry Kissinger led a diplomatic effort to negotiate a ceasefire. It was a difficult process because of the fluid lines of battle.

At the end of the business day on October 23, 1973, Kissinger met with his senior staff to give a speech. Kissinger discussed how the war had started and his views on how the Soviet Union had reacted. According to Kissinger, just before the Arab attack, both the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and National Research and the CIA produced reports indicating that an Arab attack was highly unlikely, and a similar assessment had been provided to the president in his Daily Brief. The Arab attack caught everybody by surprise, but Kissinger believed that the Israelis were the most surprised.[13]

In Kissinger’s view, the Soviets did not want the war and learned of the Arab plans shortly before the attack. He also discussed his negotiations with the Soviets. In Kissinger’s opinion, his diplomatic overtures were not merely effective, they were brilliant, and he gave himself high marks for what he had accomplished. Several of his senior staff told their boss that they agreed with his assessment of his performance.

Ray Cline, the head of the State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence and National Research, was a little less positive than Kissinger about the intelligence situation, according to a transcript of the meeting. “Our difficulty was partly that we were brainwashed by the Israelis, who brainwashed themselves, I think, in the same way,” Cline said. “But much more important, we really did not have an adequate intelligence base to work on, as to what was going on day-by-day in the Middle East.” Cline thought that the overall strategic framework was correct. “But we did not have very good intelligence, and we didn’t have nearly as much as the Russians had. And I think that is a very serious thing for the future. They had a great deal more to go on than we did,” he said, almost certainly a reference to the many Soviet reconnaissance flights compared to the limited American reconnaissance data, which consisted of a few GAMBIT photos taken soon after the start of the war, a single SR-71 mission on October 13, and nothing else.

The October 23 glad-handing session had an ironic twist. At the end of his speech, Kissinger noted that the Arabs had started complaining of something again, which he interpreted to mean that the Israelis were taking some of their territory, and that would have to be worked out diplomatically. He did not seem alarmed.

What Kissinger did not realize was that the Israelis had already penetrated rather far into Egyptian territory and significant units of the Egyptian army were at risk. The Soviet Union’s leadership was very alarmed, and there was evidence that the Soviets might directly intervene in the war.

Kissinger’s musing in August about the US facing a “cultural revolution” was a key issue during the war, because Nixon was under increasing pressure domestically. In addition to the multiple investigations of the Watergate break-in, on October 9th his vice president, Spiro Agnew, indicated that he would be resigning due to personal financial scandals. Nixon was also drinking heavily. Kissinger later explained why Nixon couldn't take a call from the British prime minister regarding the Middle East situation: “When I talked to the president he was loaded,” Kissinger said.[14]

A little over 24 hours after Kissinger had started his victory lap at the State Department, he recommended that President Nixon raise the alert level of American strategic forces to DEFCON III, the highest level since the Cuban Missile Crisis. The intelligence that led to this decision had not come from satellites but indicated that the Soviets might be moving nuclear weapons into Egypt. Kissinger and others in the US leadership believed that the Soviets had concluded—probably accurately—that the United States no longer had a functioning president.[15]

The two countries were moving toward the brink.

Ultimately, the Soviets did not escalate in response, and never intervened directly in the war. The two sides backed away from the brink faster than they had approached it, and the war soon ended. But the events of the Yom Kippur War demonstrated that some people believed the United States clearly could have used better satellite intelligence during a major international crisis.[16]

President Nixon meeting with senior leadership, including Henry Kissinger, in October 1973. During this period Nixon was under investigation and his vice president resigned due to a financial scandal. Nixon was drinking heavily, which impaired his ability to make decisions. Kissinger and others worried that this perception of a leaderless White House emboldened the Soviet Union. (credit: Nixon Presidential Library) |

The war resulted in substantial post-mortem evaluation, including of US intelligence.[17] Those assessments generally looked at three issues: intelligence leading up to the war, intelligence during the war, and the role intelligence may have played in the decision to elevate US forces to DEFCON III. As one CIA history concluded, there was substantial intelligence before the war indicating that an attack was plausible, if not likely. The problem was that US and Israeli leaders did not believe it. As for intelligence during the war, the CIA did establish a special group to provide ongoing situation reports about the conflict, particularly information necessary for negotiating a ceasefire.

| SPIN SCAN may not have affected the outcome of the war, or even superpower negotiations during the war, but it is clear in retrospect that American strategic reconnaissance during a major crisis was limited by what it could put overhead to peer into a war zone. |

Setting aside possible faulty analysis, was the intelligence data during the war sufficient for US policy makers? That question, although subjective, is still largely unanswerable today. It is clear that there was very little overhead reconnaissance of the war zone available to American leaders, forcing them to rely upon other sources of information. Had SPIN SCAN been available, it could have provided daily reconnaissance of the crisis. But SPIN SCAN was never built, and it has long been forgotten.

By late 1976, the United States began operating the first of its KH-11 KENNEN near-real-time reconnaissance satellites. They were capable of sending images down to Washington within an hour of being taken. KENNEN finally provided the crisis reconnaissance capability that people in the intelligence community had been discussing for the better part of a decade.

The Yom Kippur experience apparently weighed on the minds of American intelligence officials for many years. In a February 1980 Washington Post article, Michael Getler wrote:

For example, other sources say that when the 1973 Middle East war broke out, the Soviets had one intelligence-gathering satellite in orbit able to watch and photograph some of what was going on below. Within two weeks, there were six such Soviet satellites in orbit. The Soviets' ability to put so many additional satellites in space so quickly stunned U.S. observers.

But even though the United States had acquired a near-real-time reconnaissance capability by late 1976, a system like SPIN SCAN could have still had some value even after that. Getler added:

Panelists are studying whether the United States also should have some standby capability to restore space-borne intelligence-gathering quickly if the Soviets, with antisatellite weapons, were able to blind viewing devices of U.S. craft watching such things as missile or troop movements.(…)

One way might be to send satellites into orbit for only a short time so that Soviet ground stations cannot track them long enough to get an accurate shot.

Whatever studies were done in 1980 about developing a “stand-by” reconnaissance capability remain classified.

At that time, US policy prevented the sharing of overhead reconnaissance to all but a small number of allies, not including Israel—a policy that was apparently changed afterwards. It is possible that the strategic reconnaissance community conducted an assessment and considered the value of crisis reconnaissance during the Yom Kippur War. SPIN SCAN may not have affected the outcome of the war, or even superpower negotiations during the war, but it is clear in retrospect that American strategic reconnaissance during a major crisis was limited by what it could put overhead to peer into a war zone.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.