Commercial lunar landers prepare for liftoffby Jeff Foust

|

| “Each one of those things that we witnessed in terms of anomalies that caused the failures of those missions, we have internalized,” Altemus said. “Therefore, I think our odds are higher.” |

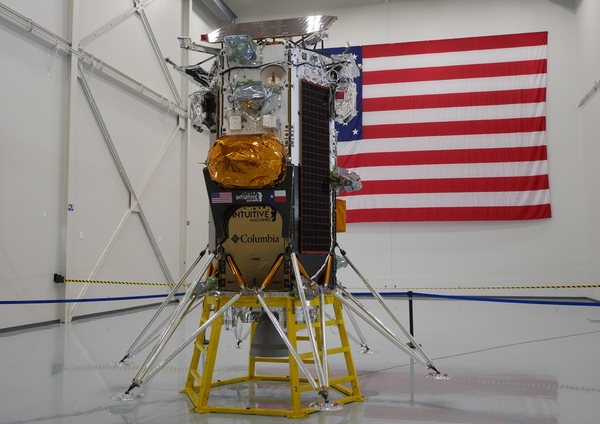

The spaceport is a launch pad of sorts, though, for another tenant. Earlier this month, Intuitive Machines showed off its first Nova-C lunar lander, which is slated to launch to the Moon in as soon as a month on the IM-1 mission. That will mark the start of both the company’s ambitions to set up lunar transportation and other services and the payoff of a bet made by NASA several years ago to foster that industry.

The lander, company officials said at the October 3 media day, is complete and ready to ship to Florida. Its launch is currently scheduled for a six-day period that opens November 16 on a Falcon 9 from Kennedy Space Center’s Launch Complex 39A.

The main concern the company had with the upcoming launch is what Intuitive Machines CTO Tim Craine called “pad congestion.” While there are two Falcon 9 pads at Cape Canaveral, IM-1 can only launch from LC-39A since that is the only pad with the equipment needed to fuel the lander with methane and liquid oxygen shortly before launch. That pad was being used for the Falcon Heavy launch of the Psyche asteroid mission—which took place last Friday after eight days of delays caused by spacecraft technical issues and weather—then will be used for Falcon 9 launches of a space station cargo mission and, possibly, an NRO payload ahead of IM-1.

“We’re working with SpaceX to try and thread the needle,” Crain said. “We’ll be ready to go on November 16, but we’ve got to work through that pad congestion.” If IM-1 can’t launch in November, Intuitive Machines has reserved a backup launch opportunity in mid-December.

If all goes according to plan, the 675-kilogram Nova-C lander will separate from the Falcon 9 upper stage 32 minutes after liftoff. Five days later, after a series of trajectory correction maneuver, the lander will go into orbit around the Moon. A day after that, it will attempt a landing at crater called Malapert A in the south polar regions of the Moon, operating NASA and commercial payloads for nearly two weeks before the end of the lunar day.

History suggests that there’s a good chance not all will go according to plan. Under half of lunar lander missions to date have successfully soft-landed on the Moon, with others crashing or simply missing the Moon entirely. In the 21st century, there have been four successful landings: China’s Chang’e-3, -4, and -5 missions and, most recently, India’s Chandrayaan-3. But there were failures in 2019 of Chandrayaan-2 and SpaceIL’s Beresheet, and earlier this year of HAKUTO-R M1 by Japan’s ispace and Russia’s ill-fated Luna-25. Japan also flew a cubesat on Artemis -1 last year called Omotenashi that was intended to make a “semi-hard” landing but malfunctioned after deployment and flew by the Moon. Four successes in nine attempts.

Company executives, while not guaranteeing success, think they can beat those odds. CEO Steve Altemus said he estimated “upwards of 65% to 75%” probability of success, based on the testing the company has done on key technologies needed for the landing, as well as the lesson learned from recent failures. IM-1, for example, has dissimilar redundant inertial measurement units to prevent a failure like that Beresheet experienced during its landing attempt.

“Each one of those things that we witnessed in terms of anomalies that caused the failures of those missions, we have internalized,” he said. “Therefore, I think our odds are higher.”

The media event took place just after the company completed a pre-ship review for the lander that confirmed there was no work left to do on the lander, having closed out all remaining open issues with the vehicle. “I feel really good,” Crain said.

Intuitive Machines is not betting the company on a single mission. Its second Nova-C, IM-2, is taking shape for a launch next year, with major components in the other side of the high bay that hosted IM-1. It is also developing IM-3 and potential future landers.

| “We’re ready, so stand by,” Astrobotic’s Hendrickson said. “The team is ready to land.” |

The company has also diversified beyond lunar landers. It is planning a lunar communications network and is bidding on the Lunar Terrain Vehicle, a rover for future NASA Artemis missions. Intuitive Machines won a NASA engineering services contract, partnering with KBR, with a potential maximum value of $719 million over five years, although the company has not disclosed its share of that award. It also recently won an Air Force Research Lab contract to work on designs of nuclear-powered spacecraft, part of a program cleverly called Joint Emergent Technology Supplying On-orbit Nuclear power (JETSON).

The company is expecting strong growth in those various markets. The IM-1 media event took place at the company’s new facility at the Houston Spaceport that will allow it to combine a workforce that today is spread over multiple offices. That building is not yet completed: reporters attending the event were escorted through offices and labs still being outfitted to reach the high bay where the lander was located.

“Look at Intuitive Machines as a diversified space exploration company,” said Altemus, who called the company “a modern instantiation of an aerospace company that is not tied to the traditional cost-plus-award-fee contracting methods of the past but can live and work in a fixed price environment, or even NASA just buying a service.”

Astrobotic’s Peregrine lander could launch as soon as December, depending on the readiness of its Vulcan Centaur launcher. (credit: Astrobotic) |

Balancing risks

Intuitive Machines is not alone in gearing up for its first lunar lander mission. Pittsburgh-based Astrobotic has its first lander, Peregrine, ready to launch to the Moon as soon as December.

“We were originally going to be ready to fly in March,” said Dan Hendrickson, vice president of business development at Astrobotic, during a panel at last month’s meeting of the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group (LEAG) in Maryland. “The vehicle has been waiting in our high bay in Pittsburgh.”

The delay is linked to the rocket launching Peregrine: United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur, whose debut mission is to send Peregrine to the Moon. Problems with the rocket’s Centaur upper stage pushed back that launch from earlier this year, but both Astrobotic and ULA are planning for a December launch, barring any late issues with the rocket or spacecraft.

“We’re ready, so stand by,” he said. “The team is ready to land.”

Both Peregrine and IM-1 are carrying payloads for NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) program under awards they received in 2019. A third company with a CLPS award is Firefly Aerospace. It announced earlier this month that it completed the primary structure for its Blue Ghost lander slated to launch in 2024.

The lander shares “significant commonality” with the company’s Alpha rocket, said Firefly’s Will Coogan at the LEAG meeting. Firefly is well underway on a second lander mission that will also deploy a spacecraft in lunar orbit before landing on the lunar farside.

A fourth venture with a CLPS award is Draper, which is leading a team that includes several partners. Among them is the US subsidiary of ispace, which is designing a lander based on a design originally called Series 2, larger than the HAKUTO-R lander than crashed earlier this year (a second flight model of which is under construction for a commercial mission launching next year.)

The company, though, has revised the design, renaming it APEX (A Pioneer In Exploration) 1.0. The new design, unveiled last month at the same time ispace US opened a new facility in the Denver suburbs, is intended to correct design challenges with the earlier Series 2 concept.

“The environmentals didn’t close on the Series-2 design, particularly in the area of vibration,” said Ron Garan, the former NASA astronaut who became CEO of ispace US earlier this year. “We needed to do a complete redesign of the vehicle in order to accommodate that.”

While the APEX 1.0 design is making good progress towards a critical design review scheduled for as soon as December, ispace said it would push back the launch of the Draper CLPS mission, called CP-12 by NASA, from 2025 to 2026.

Garan said that, despite the delay, there remains strong interest in the lander design both for that CLPS mission and potential future commercial ones. “We’re going after both commercial and government contracts to supplement CP-12. We have payload capacity right now,” he said.

| “If one of the first couple of landers isn’t successful, we’re not going to call the program a failure,” said NASA’s Connelly. |

Those upcoming launches will put to the test the “shots on goal” philosophy that NASA officials set out for CLPS when they rolled out the initiative more than five years ago. The expectation then was that not every mission would be successful—not every shot would make it into the goal—but that enough would be successful at much lower costs than traditional missions to be worth some failures.

The agency has already dealt with failure before the first lander made it to the launch pad. One of the companies that received a CLPS award was Masten Space Systems, but that company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in July 2022. Astrobotic acquired most of Masten’s assets, but not the CLPS award, and NASA has been working to reassign payloads that had been manifested on that lander to other CLPS missions.

“Nobody likes losing $60 million, but this was one of the risks that we identified with the model that we created,” said Chris Culbert, NASA CLPS program manager, at the LEAG meeting. NASA leadership, he said, was “relatively accepting” of that failure, but directed the program to make changes to prevent it from happening again.

“We’re working to understand the financial risk that vendors are taking on” with CLPS awards, he said. “Now we’re making sure they’re not taking too much risk on. You can argue that Masten took too much risk on and was not able to recover from that.”

Other agency officials say they will be tolerant of technical failures on the upcoming CLPS missions. “If one of the first couple of landers isn’t successful, we’re not going to call the program a failure,” Sandra Connelly, NASA deputy associate administrator for science, said at a meeting of the NASA Advisory Council’s science committee in August.

“This is one of those high-risk, high-reward scenarios,” she said of the CLPS missions. “We do expect roughly a 50% success rate.”

That’s more pessimistic than what Intuitive Machines’ Altemus predicts for his mission, but a little better than the historical average. In a few months, we should see what companies, if any, can beat those odds.

Note: we are using a new commenting system, which may require you to create a new account.